While Disney is the unchallenged king of animated movies, certainly in the forties and fifties, I don’t intend to explore all his movies, as really, once he kickstarted the, well, industry you’d have to say, much of his output, though still excellent, is intrinsically unimportant to the advance of animation: more of the same, basically, and I have no intention of recounting the history of Disney. I’ve acknowledged his rightful place in the history of animation, and in all likelihood I’ll come back to him later, but I’d like to just set him aside for now and look at what else was happening in the 1940s in the USA in terms of cinema animation.

Before I do, though, one final accolade to Uncle Walt. With the release of Dumbo (1940) and later the already-mentioned and long-delayed Bambi (1941), Disney introduced the idea of anthropomorphism, in other words, the assigning of human emotions, actions and thoughts to at first animals but later even inanimate objects, as we have seen with the likes of Pixar’s Cars and Planes. Up to then, with the exception of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, animated movies had featured humans, or human-like creatures such as dwarfs (they’re in some small animated movie released around 1937, you probably haven’t even heard of it) and while things like squirrels, birds and other animals were in this movie they acted as squirrels, bird and other animals. They didn’t talk, they didn’t show any real sense of reasoning. Rabbits ran if trouble threatened, birds flew away. Birds tweeted, squirrels, well, did whatever squirrels do. Honest John and Gideon did certainly make a case for anthropomorphic creatures in Pinocchio, as did Jiminy Cricket to an extent, but Dumbo was the first animal to star in their own movie and have it built around them, and as far as I remember, though that had some humans in it Bambi, which followed (though it was written before Dumbo) had none at all, so you were really taken into a different world, the forest the animals lived in.

But Disney was breaking down so many barriers and winning awards left right and centre, and setting the standard for the genre, what was left for those who would be his competitors to do? Well, I’m glad you asked.

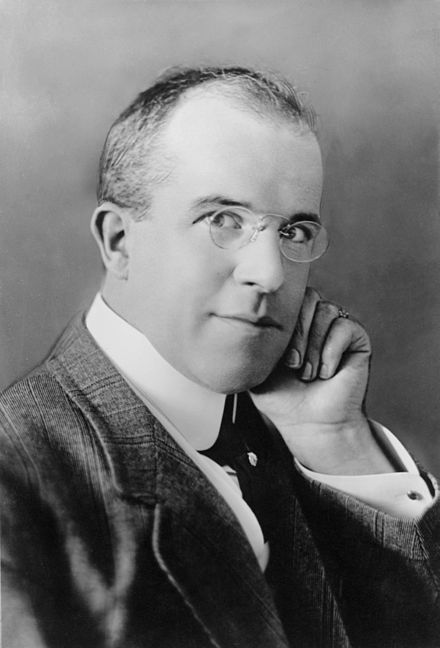

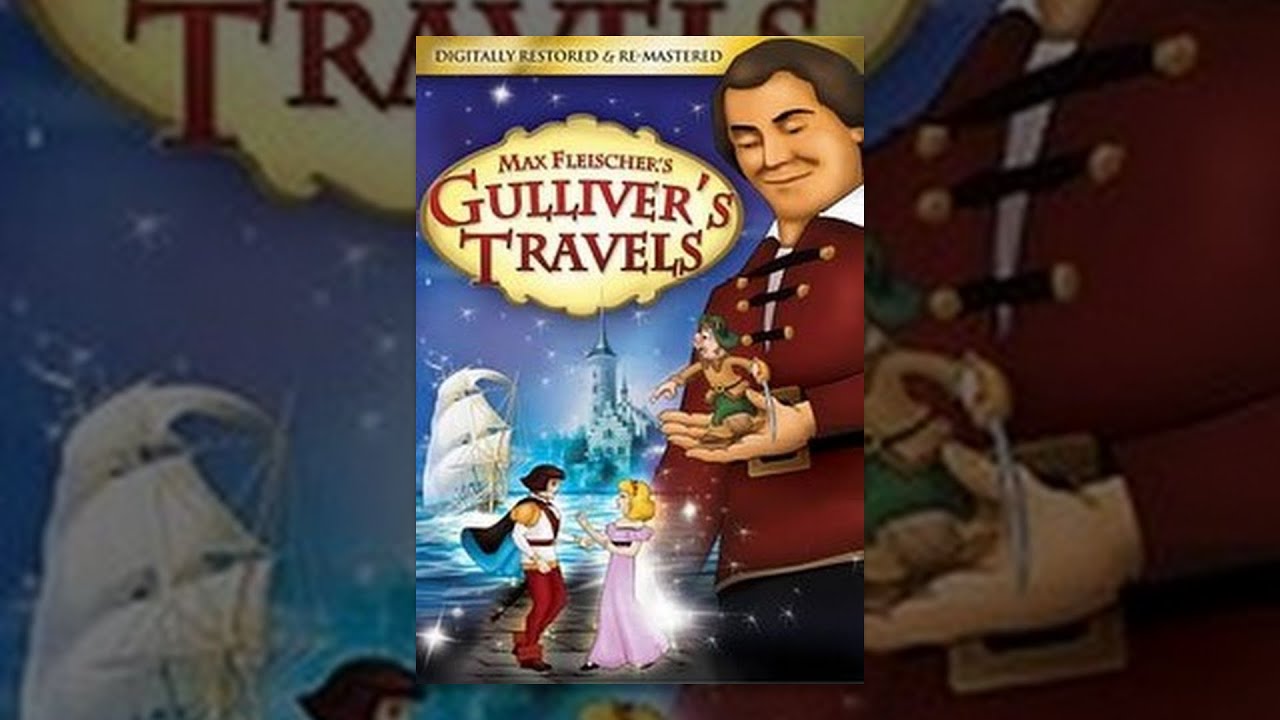

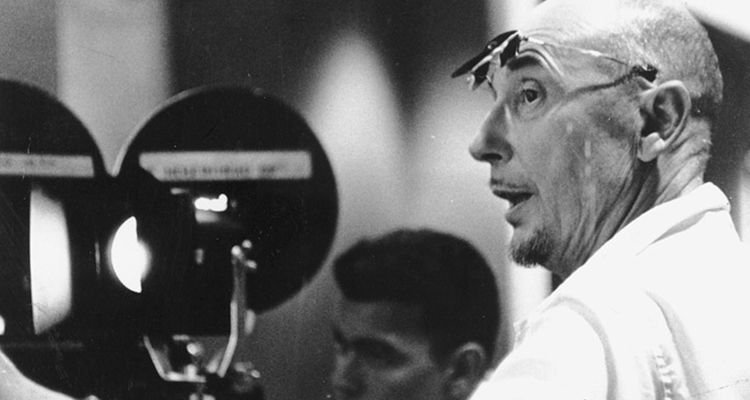

Remember this guy?

Though his last (and first) real full-length animation, Gulliver’s Travels had been released in 1939, and it might seem Max Fleischer had not done much since, nothing could be further from the truth. Sure, he had yet to produce another full-length animation, but as I mentioned in a previous entry, he was already very popular for two cartoon characters who would challenge the dominance of Mickey and Donald, and who are both known to just about everyone reading this, if only by reputation.

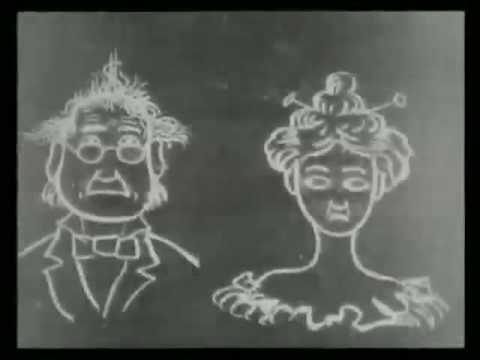

Betty Boop (Created 1930)

Originally created as an anthropomorphic poodle figure as part of a series of shorts created by Fleischer called Talkaroons, Betty appeared in the fifth instalment as a companion to another popular character, Bimbo. Very quickly, as her own appeal became obvious, her form was changed into a far more human woman, and Bimbo, who had been positioned as the star and a potential rival to Disney’s big guns, especially Mickey Mouse, faded out. Supposedly based on singer Helen Kane, Betty was depicted as a 1920s “flapper” girl, and it is perhaps ironic that while her male companion Bimbo was named as such because at that time, the word meant a man ready to fight, she would come to encompass what we would call today the characteristics of a bimbo. If I hadn’t known better, I would have thought she had been based on Marilyn Monroe, though of course at this time Norma Jean Baker was a child of four years old. At any rate, Betty soon progressed beyond her role in the Talkaroons and acquired her own strip, becoming one of the most loved and well-known cartoon characters ever.

Although originally designed by Grim (seriously? A cartoonist called Grim?) Natwick, the transformation from canine to human was mostly attributed to five men – Berny Wolf, Seymour Kneitel, “Doc” Crandall, Willard Bowsky and James “Shamus” Culhane. I honestly can’t think of another cartoon character so expressly sexual and attractive until 1988’s Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (in which she has a cameo herself), when Jessica Rabbit made us lads all lust after a cartoon woman. She really is proportioned (other than her head) as a totally sexy woman, and her “Boop-oop-de-doop” line is maddeningly sexual too. Fleischer would create firsts of his own, rivalling Disney for the honour of presenting the first properly-proportioned sexy female cartoon character (and this in an age where sexual attitudes were still very repressed) and indeed be the first to portray sexual harassment onscreen in a cartoon, when in Boop-Oop-a-Doop (1932) she is threatened with rape by a villainous ringmaster and only saved by another character. That’s strong, strong stuff for eighty years ago!

Betty’s cartoon series lasted from 1932 to 1939, but the interference of that bastion of the guardians of public morality, the censor, particularly the National League of Decency and the Production Code, both forced Betty into a more conservative, less sexy role, and she began to be eclipsed by her support characters from about 1935 on. Though there were two television specials, in 1985 and 1989, Betty did not make the same transition to the small screen as did Fleischer’s other, more popular character.

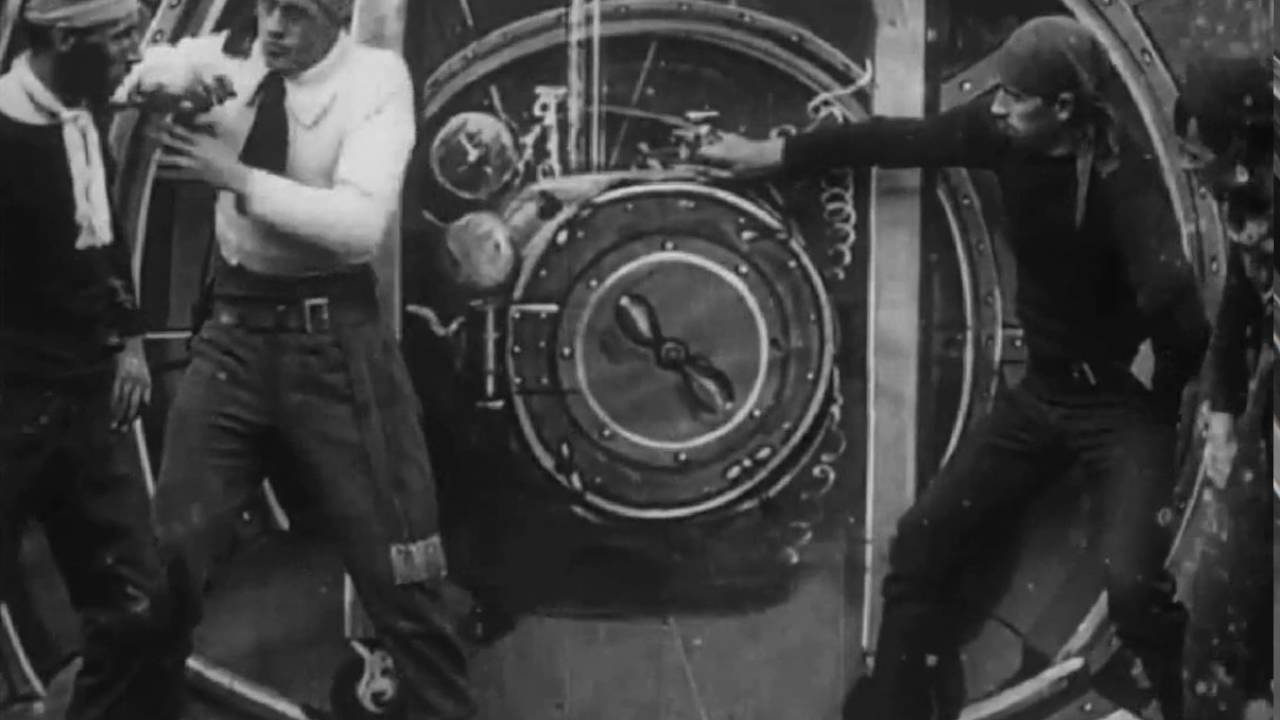

Popeye (the Sailor Man) (Created 1932)*

The first of his characters not to be created by his own studios, Popeye was licenced by Fleischer in 1932 from King Features, the publishing firm owned by William Randolph Hearst, in whose New York Journal daily comic he had starred since 1929, having been created by Elzie Crisler Segar as a bit-part player in her series Thimble Theater. He instantly became so popular that not only was he brought back quickly, he took over the series and became one of the best known cartoons at that time. His appeal still lasts today, where his cartoons are regularly played all over the world.

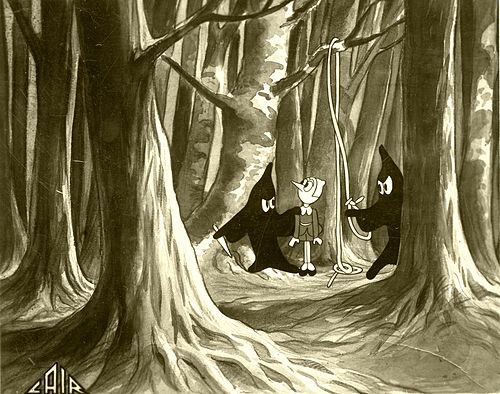

Unlike Walt Disney’s cute creatures and cuter people, Max Fleischer preferred to draw his characters in a more abstract, caricaturistic way, and with more down to earth settings reflecting the Great Depression through which he lived. Working in black and white a lot longer than Disney he used the medium to his advantage rather than feel restricted by it. I suppose you could perhaps call his cartoons a sort of film noir, certainly compared to Disney’s more kid-friendly, happy and uplifting style. Or to put it another way (and anyone familiar with his work and/or film in general, correct me if I’m wrong, as I may very well be) if Disney was animation’s Spielberg then Fleischer was its David Lynch. His cartoons were rougher drawn, more symbolic and surreal, and often contained hidden (or sometimes not so hidden) messages of sexual innuendo. They were also, in general, darker in content than Uncle Walt’s stories of happy forest creatures or flying elephants. This in itself I guess probably prevented Disney from really seeing Fleischer as a threat (even though they were personal rivals); they were almost working at opposite ends of the spectrum, and with Disney moving on to full-length features while Max was still producing Betty Boop shorts, it seemed unlikely the one would ever challenge the other.

Popeye however did become immensely popular, starring in his own series of movies. Fleischer’s last ever full-length feature, Mister Bug Goes to town (1941) was a complete disaster. Apart from the fact that a rift had developed between Max and his brother Dave, to the point where they only communicated in writing while working on the movie, it was released two days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor signalled the US’s entry into World War II, and Paramount lost their shirts on it. They demanded the resignation of both brothers, which they duly got, and moved in to take over the studios.

Under new management and in really what amounted to a new world now, Popeye became a war hero, starring in shorts in which he dealt out American justice to the Nazis and the Japanese. The studios were renamed Famous Studios, and in 1943 Her Honor the Mare became the first Popeye short to be released in colour. Although he was now gone, Fleischer’s long association with black and white cartoons was forcibly over, and Popeye was dragged into the world of colour cartoons. In 1957 Paramount sold the rights to Popeye and three years later he made his debut on the television screens of America, but we’ll pick that up when we get the the TV era in this history.

Popeye was of course a sailor (more of a sailor than Donald Duck, as he actually did go to sea) and had average strength until he ate spinach, which increased the size of his muscles and allowed him to take on whatever foes he was facing. Whether the idea of using spinach was a marketing ploy or just coincidental, it did succeed, as American (and later British) kids started eating more spinach so as to be just like the cartoon sailor. So influential was he on the sales of spinach that several statues to him were erected, including one in Chester, Illinois, home of his creator, Alma, Arkansas, said to be “the spinach capital of the world” and Crystal City, Texas. Popeye had an entourage of supporting characters, originally the main ones in the Thimble Theater series, such as his girlfriend Olive Oyl, Wimpy, The Sea Hag and Bluto or Brutus, his eternal nemesis and rival for Olive’s affections.

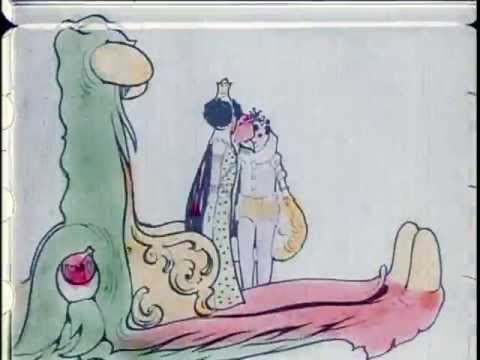

Prior to their forced departure and the takeover of their studios, the Fleischer brothers had reluctantly accepted a commission to bring the comic book character Superman to life on the screen, and though they quoted what they believed to be an exorbitant price per episode, citing the difficulty of working in Superman’s world and bringing Metropolis alive, they were bargained down and ended up being stuck with the project. Although Superman ran for a total of seventeen episodes, the Fleischers only created nine. The remaining eight are generally considered inferior to them, as the original ones had a more science-fiction theme, while the later ones leaned more in the direction of WWII propaganda films, and were created by a team of animators made up of Seymour Kneitel, Isadore Sparber, Sam Buchwald and Dan Gordon. Kneitel had worked on the humanisation of Betty Boop for Fleischer, if you remember, so he was obviously kept on by Paramount/Famous.

One thing the Fleischers apparently are credited with, rather amazingly if it’s true, is the power of flight for Superman. In the Action Comics, he was only able to leap from building to building, but when the brothers originally animated this it looked silly, and they decided to have Superman fly instead. Action, and later DC, okayed this and had the ability written into the character’s canon. I think I’m also correct (though admittedly I’ve not researched it) that the Superman cartoons were a) the first time a superhero had been depicted onscreen b) the first time a superhero had been animated onscreen and c) the first time a character had appeared onscreen in an animation which had originally taken place in comics (as opposed to a newspaper strip, a la Popeye). So again, keeping up with Disney by pioneering the way and planting a few milestones of their own, these guys.

Later on of course, the series would follow Popeye across the divide to television, where it would entrance a whole new and younger audience, and reawaken interest not only in Superman but in superheroes, leading to such series as Batman: the Animated Series, Spiderman and others, and writers such as The Dark Knight’s Frank Miller would quote the cartoons as a major influence on his writing. DC would honour the Fleischers by naming them as one of The Fifty Who Made DC Great in 1985. Max himself would succumb to Arterial Sclerosis of the brain and pass away in 1972, earning himself the title of “the dean of animated cartoons.” Dave would survive him by seven years, taken in 1979 by a stroke. Both would outlive Walt Disney, who passed away in 1966.

** Refers to the creation of the character for animation purposes; Popeye was originally created in 1929*