Lotte Reiniger

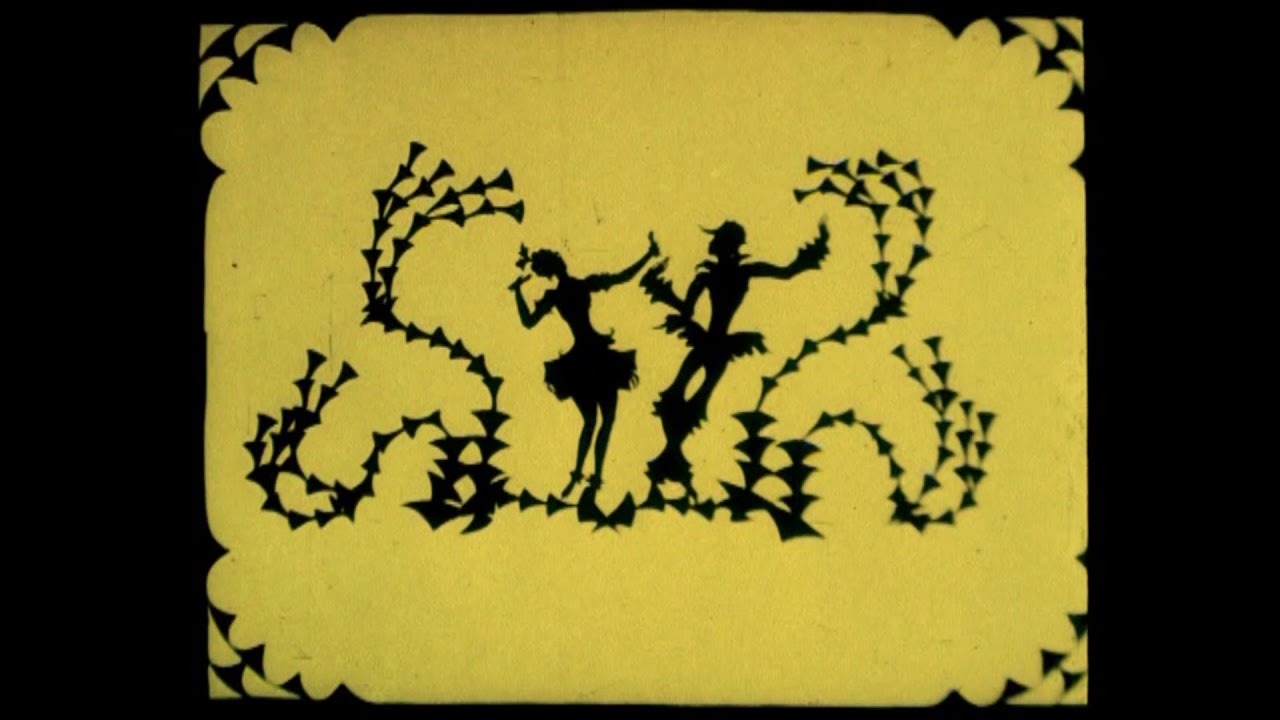

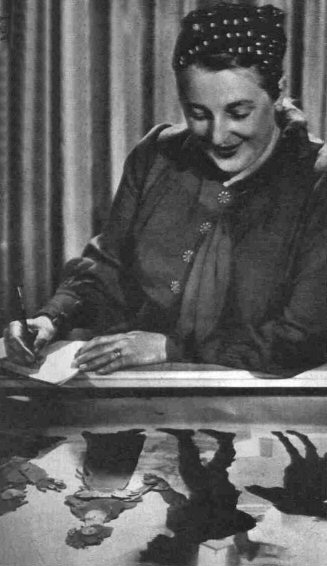

Perhaps Germany’s greatest animator, we have already come across Reiniger as she produced the first feature-length animated film almost ten years before Disney’s game-changer, but she also created a lot of shorter animations. Her first real effort was in 1918, when she animated wooden rats for the film “Der Rattenfänger von Hameln” (The Pied Piper of Hamelin) which brought her to the attention of, and obtained for her enrolment in, the Institute for Cultural Research, where she would meet artists such as Bertolt Brecht and Berthold Bartosch, already mentioned, and the man she would marry and work with, Carl Koch. She quickly began to make herself known in the world of animation, her first proper film, “Das Ornament des verliebten Herzens” (The Ornament of the Enamoured Heart) actually selling out in the USA in 1919, and found herself working with the previously-mentioned Oskar Fischinger and Walter Ruttman, who with some others became the heart of German animators.

When she was approached to film Prinzen Achmed she faced stiff opposition: up till then, animation were basically cartoons, meant to make people laugh, and short usually too. This would be an entirely different proposition, and everyone she approached in her country turned away horrified from the very idea, damning the project to failure before it had even started. But once she secured financing and the film premiered in Paris, it became a huge hit, and is now considered one of the most important of the early animated films, a true triumph. Reiniger also pioneered the very first Multiplane camera - Wikipedia, or its ancestor at any rate, and she went on to make many animated features, including “Doktor Dolittle und seine Tiere”(Doctor Dolittle and his Animals"), 1928.

Like her contemporary, Fischinger, Reiniger found the situation in Germany as the Nazis rose to power too untenable, and she fled the country, but unlike him she was unable to go to America, not having been invited there, and in fact no country would give her and her husband permanent sanctuary, necessitating their moving from country to country as temporary visas ran out, over a period of more than ten years, which in fact led up almost to the end of World War II, but for a year or more she had to work under Hitler’s rule and make propaganda films for his party. Eventually she would make it to London, but not for another five years.

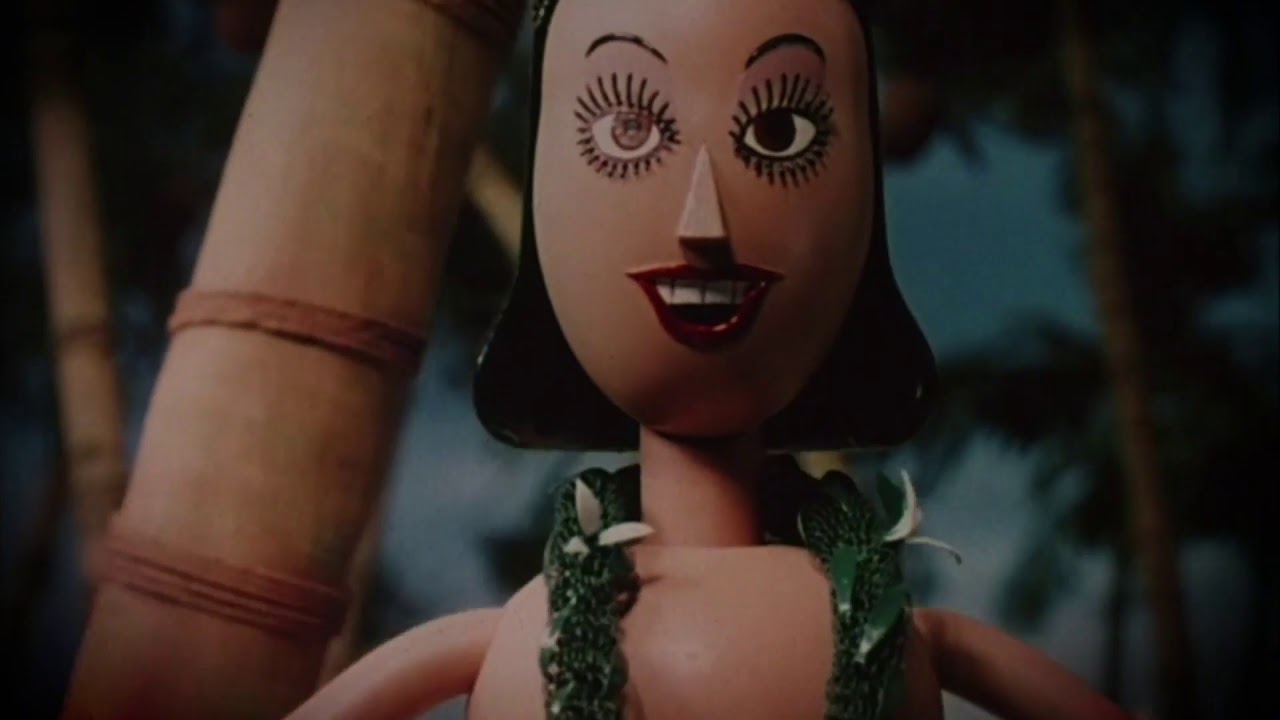

Meanwhile, Hungarian-born George Pal actually came from his native country to work in Germany, having set up a company to produce advertising films, and he became quite famous there until the Nazis came to power and he became another forced to flee Germany. He would later work on such seminal science-fiction films as The Day the Earth Stood Still, War of the Worlds and The Time Machine , making his name in the USA as a producer. Before that though, in 1940 he became famous for the Puppetoons series, which featured, oddly enough, puppets. In fact, he won an honorary Oscar in 1943.

Other German animators working prior to the outbreak of the war included Alexander Gumitsch, who used clay figures in a time long before what became known as claymation, and Alexander von Gontscharoff-Mussalewsky, who used plastic figures, but unfortunately his animations tended to contain racial stereotypes, such as “a stupid negro”; Richard Groschopp, whose short “Die Wundersamen Abenteur des kleinen Mutz (A Boy’s rocket flight to Planet X)” won the runner-up prize at the International Amateur Film Festival in London in 1935, and the follow-up to which was included on a Nazi propaganda film, earning it much more acclaim and widespread distribution.

The Search for the German Answer to Mickey Mouse: Elves, Bunnies and Frogs, Oh My!

In 1935 UFA, the largest and most successful animation company in Germany (their equivalent, basically, of Disney in Germany), commissioned cartoonist Otto Waffenschmidt to create a new animated cartoon character, and he settled on an elf from German folk tales, called Tilo Voss. However Waffenschmidt had not the experience of comic books and newspaper strips that were available in the USA, and his initial effort was rejected for not having “enough gags”. Unexpectedly spiralling running costs then added to their problems and in the end the project was shelved, leaving the task of creating a German cartoon character to Ultra Film in 1937. However their music director, Herr Julius Kopsch, who had been asked to create a score for the film, which was to be entitled “Die drei getreuen Haschen (The Three Faithful Bunnies)” did not seem to like bunnies, and wanted to to use dogs in the film instead, and the project stalled. Finally, in desperation UFA turned to an animation studio in Paris, who promised to give them what they wanted, but shortly afterwards Snow White hit, and the rules of the game were forever changed.

The man who wrought that change upon the world visited Germany himself in 1935, though who Disney met with there is unclear, and no documents pertaining to the visit survive, but interestingly enough, Snow White became the only American movie of any kind to be passed by the German censors under Hitler’s regime. Make of that what you will. Also telling is a report from a German trade paper which described Josef Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda guru, as “Disney’s No. 1 fan”. In 1937 the former mayor of Graudenz, Max Winkler, who had become a big wheel in German cinema, was promoted to head of the German film industry by Goebbels, though here I find something of a problem is cropping up. In some accounts of animation under the Hitler regime there appear to be disparities, even conflicts. One says that the Nazis viewed animation as a “degenerate art” while another cites Hitler’s love of Mickey Mouse and Snow White. The abovementioned Winkler is spoken of in Animation Under the Swastika: A History of Trickfilm in Nazi Germany, 1933-1945 by Rolf Giesen and J.P. Storm but not even referred to in my main reference for this journal, Animation: A World History by Giannalberto Bendazzi , even in the section which specifically deals with Nazi Germany. I suppose reliable records from that time might be harder to verify than expected.

Deutche Zeichenfilm GmbH (The German Animation Company), set up by Hitler and Goebbels in 1941, found its base changing as the Allies continually bombed Germany, eventually situating itself right beside Dachau. (Could there be sharper irony than to have a place dedicated to what is ostensibly fun sitting side by side with a death factory of human misery and extermination?) Art Director at the time, Gerhard Fieber, would later recall ”During the working hours you were busy with trickfilm figures, at the same time you could see prisoners on the street who were harnessed in front of wagons as replacements for horses. Nevertheless you had to draw funny figures – it was awful.” I’m sure it was; makes you wonder why he chose to relocate to that particular area. Probably had little choice as the war wore on.

Despite the studio being unsuccessful, Goebbels directed DZG to create a ten-minute animation called “Hochzeit im korallenmeer (Wedding in the Coral Sea)” which was actually produced in Prague, and here again we have a problem: as Nazi Germany was occupying most of Europe from 1940 to 1944, any Nazi animation really has to be credited, as it were, to them. I don’t really see any other way to do it, as I doubt, for instance, Czech animators today would wish to be associated with a Nazi-made film, though I may be wrong. I’m erring on the side of caution, anyway, and lumping them all together, as the book title I mentioned earlier says, under the Swastika.