Title: Wake Not the Dead

Format: Short story

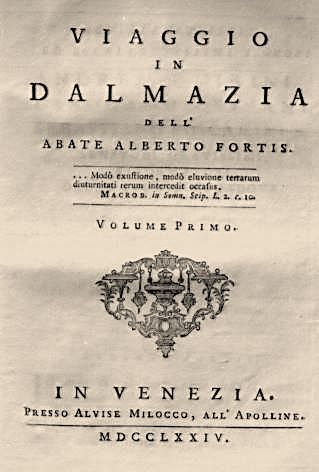

Author: Ernst Raupach (though often cited, incorrectly, as Johann Ludwig Tieck)

Nationality: German

Written: 1823

Published: 1823

Synopsis: A cautionary tale, a romance of sorts, a fairy tale and a horror story all in one, and one which exposes the frailty of man, Wake Not the Dead follows Walter, a Burgundian lord who loses the love of his life when his wife dies. Rather unfairly, as the story opens, he’s remonstrating with her spirit as he sits at her grave, asking why she won’t come back to him? He marries again but can’t put the memory of his dead wife, Brunhilda, out of his mind. Some time later he meets a sorcerer who tells him he can bring her back to life, but as always, there are consequences and Walter should heed his warnings, think about what he is agreeing to.

He points out to the lord that he himself has aged, whereas Brunhilda, were she to come back from the grave, would be as young as when she died. He doesn’t listen. The sorcerer then warns him of the horrors of disturbing the peace of the dead, raising a corpse from its sleep. Falls on deaf ears. For three days he warns Walter, forcing him to wait, consider what he asks, return the next night, and every day that passes the lord gets more and more impatient, and more set on having his wife back. Finally, almost with a shrug and a “on your head be it, I’ve done the best I can to dissuade you”, the sorcerer does his thing and the wife is brought back to life. The sorcerer tells Walter that if things don’t turn out as he expected, he should seek him at the crossroads when the moon is full.

They spend twenty-one days at his “other” castle, not his palace where his second wife, Swanhilda, lives with him, nobody aware of Brunhilda’s resurrection, even of her presence, but him and one old retainer who has been told to button it if he knows what’s good for him. She uses this time to get used again to the light of day, and perhaps to fully form back in the land of the living; it’s left a little vague, sort of like Jesus, after his rising, reportedly saying that he can’t be touched as he hasn’t yet ascended. She however will only be with Walter if he divorces his second wife, so that she can move into the palace. Well, you don’t have to come back to the dead as the original wife to have those kind of conditions. Get that bitch OUT of my house or no nooky for you, son! So he does, giving her the “it’s not you it’s me” speech. Actually, he tells her it is her, and divorces her.

In a rather unlikely twist, Swanhilda seems to have sussed him: “Too well do I conjecture to whom I am indebted for this our separation. Often have I seen thee at Brunhilda’s grave, and beheld thee there even on that night when the face of the heavens was suddenly enveloped in a veil of clouds. Hast thou rashly dared to tear aside the awful veil that separates the mortality that dreams, from that which dreameth not? Oh! then woe to thee, thou wretched man, for thou hast attached to thyself that which will prove thy destruction.” Oh, and you can keep the fucking kids, pal. Actually, it’s the custom and the law that she can’t take them, and she seems upset to leave them behind, but has no choice.

He engineers Brunhilda’s return to his home by pretending she is just a ringer for his dead wife, though whether or not he calls her Brunhilda or Brunhilda II or Brunhilda V 2.0 I don’t know, however the staff see through it, especially when they notice a birthmark on her back that the original Brunhilda had. Rumours begin to circulate through the palace, and people no doubt start checking the want ads. Then again, there probably aren’t too many openings for those who include on their CV have served under a dead mistress, brought back from the grave. References can be obtained from the below-named cemetery… In the event they all hand in their notice, and who would blame them? Brunhilda, in what became classic vampire behaviour, avoids the sun, walking only at sundown, and shivers at the sound of the cock crow.

Unfortunately for him, as Raupach explains, Brunhilda has undergone transformation into a vampire. Oh, shock horror! It was necessary that a magic draught should animate the dull current in her veins and awaken her to the glow of life and the flame of love–a potion of abomination–one not even to be named without a curse–human blood, imbibed whilst yet warm, from the veins of youth. This was the hellish drink for which she thirsted: possessing no sympathy with the purer feelings of humanity; deriving no enjoyment from aught that interests in life and occupies its varied hours; her existence was a mere blank, unless when in the arms of her paramour husband, and therefore was it that she craved incessantly after the horrible draught. It was even with the utmost effort that she could forbear sucking even the blood of Walter himself, reclined beside her.

Whenever she beheld some innocent child whose lovely face denoted the exuberance of infantine health and vigour, she would entice it by soothing words and fond caresses into her most secret apartment, where, lulling it to sleep in her arms, she would suck form its bosom the war, purple tide of life. Nor were youths of either sex safe from her horrid attack: having first breathed upon her unhappy victim, who never failed immediately to sink into a lengthened sleep, she would then in a similar manner drain his veins of the vital juice.

It might seem odd that, with all this mountain of evidence before him, as his staff and the villagers are wiped out regularly, old Walter doesn’t twig, but love is blind, and I feel that even if he had understood what was going on, he seems such a selfish bastard that he would have convinced himself to do nothing about it. But for the sake of argument let’s assume he’s under a spell, as he may very well have been. Okay, Raupach says he is. By day she would continually discourse with him on the bliss experienced by happy spirits beyond the grave, assuring him that, as his affection had recalled her from the tomb, they were now irrevocably united. Thus fascinated by a continual spell, it was not possible that he should perceive what was taking place around him.

Plus, he was a selfish cunt. (This is not a quote from the story).

Unseen by his eyes then, everyone around him vanishes as those who are not killed by his vampiric wife get the puck out of there, and the castle is left standing alone, nearly the model perhaps for later Castle Dracula.

Brunhilda though can see what’s happening, and worries that her source of food is drying up, so Swanhilda’s children are next on the menu. Gotta drain something, you know? When Walter laments the loss of his children, she is less than understanding: “Why dost thou lament so fondly,” said she, “for these little ones? What satisfaction could such unformed beings yield to thee unless thou wert still attached to their mother? Thy heart then is still hers? Or dost thou now regret her and them because thou art satiated with my fondness and weary of my endearments? Had these young ones grown up, would they not have attached thee, thy spirit and thy affections more closely to this earth of clay–to this dust and have alienated thee from that sphere to which I, who have already passed the grave, endeavour to raise thee? Say is thy spirit so heavy, or thy love so weak, or thy faith so hollow, that the hope of being mine for ever is unable to touch thee?” Thus did Brunhilda express her indignation at her consort’s grief, and forbade him her presence.

With everyone else dead, she turns to feeding on her husband, and he begins to weaken. She doesn’t care; if/when he dies, she intends to fuck off from the castle and go hunting for some takeaway food. But speaking of hunting, Walter takes to this in an effort to regain his strength, and while out one day he comes across a strange bird which drops a root at his feet. He eats it, but it tastes yucky and he throws it away. Unbeknownst to him, it’s a charm against his bloodsucking reanimated corpse of a wife. Catching her in the act, when her spectral breath suddenly no longer works on him, he realises (finally) what she is. She’s unrepentant, and has an odd accusation to make of him.

“Creature of blood!” continued Walter, “the delusion which has so long blinded me is at an end: thou are the fiend who hast destroyed my children–who hast murdered the offspring of my vassels.” Raising herself upwards and, at the same time, casting on him a glance that froze him to the spot with dread, she replied. “It is not I who have murdered them;–I was obliged to pamper myself with warm youthful blood, in order that I might satisfy thy furious desires–thou art the murderer!”–These dreadful words summoned, before Walter’s terrified conscience, the threatening shades of all those who had thus perished; while despair choked his voice.

You know, in ways, it’s hard to argue with that. If he hadn’t wanted to get it on with her after she’d died, if he’d left her where she was and been happy with Swanhilda, nobody else would have died. In a very real manner, all those deaths - including those of his children - are on his hands. Despite his attempts to get away from her, it seems they’re bound together as if they were tied by some magic elastic, and it will stretch but not break, so he is always recalled to her at night, against his will. He has, literally, made his bed and must lie in it now.

Going out of his mind, he remembers the words of the sorcerer and high-tails it to the crossroads, where the sorcerer, with a snide “I told you so” tells him the only way to be free of the vampire is to kill her during the night of the new moon, when she is helpless. He gives Walter a special dagger he must use, and warns him that once she is dead (again) he must never think with love of her, or she may come back again.

As time goes on and he keeps cursing Brunhilda’s memory, he realises sadly that nobody will talk to or come near him; he is as a phantom among the living, doomed, as his vampire wife swore, to perdition. In desperation he seeks out Swanhilda, and she seems to feel sorry for him, but when he is forced to reveal that the corpse bride ate their children, the deal is off and he is sent packing, back out into the lonely world to contemplate his folly, what he had and what he lost.

On his way home he meets a woman who looks like Swanhilda, and they become friends. As love begins to blossom again in his heart, though it isn’t specifically referred to as far as I can see, it must be that he thinks of Brunhilda without cursing her, or softens towards her memory. Then, as you do, the other woman (never named; only called “the unknown”) turns into a giant snake, which is the kind of thing that can really ruin your day, and crushes Walter in its coils, burning down his castle for good measure.

Two years after The Black Vampyre and almost forty-five after Leonore, there are similarities to both stories here. Yes, I know one is a poem, but it can be two things! In Leonore we have Death riding on a horse (can’t remember if it’s black but it probably is) and after Brunhilda is resurrected Walter finds “a coal-black steed of fiery eye” awaiting him to bear him and his newly-undead wife away, and in order to perform the resurrection, the sorcerer pours blood from a human skull into her coffin, much as the Moor prince poured blood in a golden goblet into the graves of the husbands of Euphemia in The Black Vampyre.

I like the attention to detail as they leave the cemetery; the sorcerer (or someone) has laid on clobber for Brunhilda, so she doesn’t have to ride off like an undead Lady Godiva, or in her corpse shroud, or whatever she was buried in. A girl appreciates these things. There’s a novel treatment here of the later accepted aversion of vampires to light or the sun. Brunhilda says her eyes cannot bear the light yet (being in a coffin for years will do that to you I suppose) and so they have to acclimate her by degrees, using first candles then slightly opening the curtains over the course of fourteen days, which is I imagine significant, seven being a powerful number in magic. There’s also a sense here of her slowly returning to life, kind of similar to how Johnny Smith, coming out of his coma in Stephen King’s The Dead Zone, couldn’t leap out of bed and go for a coffee: it took him weeks or even months to slowly drag himself back into the world of the living, having been asleep and so weak for so long.

The idea of forbidden love - very forbidden, virtually necrophilia! - is explored here, as even though he loves her, Walter can’t repress a shudder every time he’s near her; his own psychic sense or if you prefer, his soul, or even God, telling him how wrong this is, as the sorcerer tried and failed to do. Brunhilda is not aware of his aversion: “Here will we tarry,” she tells him, “until I can endure the light, and until thou canst look upon me without trembling as if struck with a cold chill.” She makes him forget the bad old days, that despite how he remembers it, everything was not rosy in their garden before she died. “while he listened to her siren strain, he entirely forgot how little blissful was the latter period of their union, when he had often sighed at her imperiousness, and at her harshness both to himself and all his household.” Indeed.

Incidentally, when Swanhilda leaves she is said to have “consecrated her children with the holy water of maternal love”, this being her tears. If she had splashed them with actual holy water, she might have protected them against the vampire. Intriguingly (I’m getting tired of saying interestingly, though it is) the author here seems to indicate that vampires can’t abide gold, as Brunhilda will wear no jewellery of that metal, though she can wear silver, which later - in some few instances - was said to be dangerous to vampires, their Kryptonite. I feel this got a little mixed up with the legend of werewolves, but however.

Seven crops up a lot here. Seven days Brunhilda waits in the castle with Walter, as related already, trying to get her eyes sorted, then another seven, then she makes him wait seven more before she’ll put out (and even THEN she won’t, unless he marries her again). Then when he goes to see the sorcerer he has to spend twice seven days in a cave hiding from his vampire wife till the night of the new moon. Again, seven days after declaring his love for “the unknown” woman he marries her. Seven and three, both important magical numbers. Three times the sorcerer warns him before raising Brunhilda from the dead, three times seven days before he can bring home his new vampire wife, and three wives in all, the last of which kills him, the snake.

This is really - what’s another word for interesting? No, I used intriguing already. Where’s my thesaurus? Let’s see: no help there either. Compelling? Well anyway, it’s the first time I can see that the actual origin of a vampire is attempted. Okay, the Moor prince, but we’re not told how he became a vampire, or maybe the child was one already - after all, he couldn’t be killed. No, I think this is the first - certainly the most well thought-out and detailed - example of a Wiki Howto on the creation of a vampire. It wouldn’t be used again much if at all: the idea of a vampire rising from the grave only worked once they had already been made one, and the most popular and usual way was for another vampire to make them. The modern, as it were, idea of a vampire seems to be that they never actually died (although Rice does have her vampires go through “the human death” before they can join up the nightcrawlers club) but possess, through their vampirism, lives extended to near immortality.

It’s also the first time a vampire is created either against its will or without its knowledge. Brunhilda is dead, happily waiting for eternal resurrection on Judgement Day, and doesn’t ask for or expect to be climbing out of her coffin, shaking the graveyard dirt from her hair and dislodging startled worms who had assumed they were in for the night. It’s all achieved through the agency of a mortal, one who can’t accept loss or death, and done for entirely selfish (and, let’s be honest, not very well considered) reasons. But Raupach doesn’t allow this to make us feel any sort of sympathy towards or pity for the vampire; she didn’t ask to be Born to Darkness (copyright Anne Rice, 1975) but now that she’s up and about, she isn’t going to be shy about using her powers, so there’s no “ah poor woman look what happened to her.” Oh no. She’s a monster, and must be destroyed.

The moral is good too, in that the one who started it all gets his comeuppance in the end, though to be honest living as a shadow among his fellow humans, eternal loneliness for the rest of his life should have been punishment enough, i think. The idea of the snake is just stupid, unless it’s meant to be a gigantic worm, in which case, well, it’s still stupid. Terrible ending to a really really good story.

One final point: about three times Brunhilda is described as “terrific”, but it’s clear that here the author is using the word in its original form, whose meaning was to terrify or be terrible. Odd to think how the meaning has changed so almost completely in reverse, so that now terrific means something good, or better than good, when back then it was a description of the worst kind of thing. How words change over time.

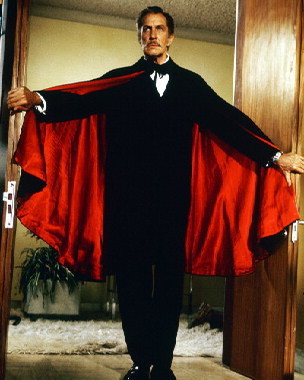

Throughout our history, one figure has lurked in the darkness of our collective hearts, haunted our nightmares, fired our imagination and fed our curiosity. For many of us, our first encounter with the creature known as a vampire was through the writing of Bram Stoker, or perhaps through Hollywood’s later interpretation of his horror classic Dracula, but this was written just over a century ago, and itself was partially based on a person who existed, who lived four hundred years previous to that.

Throughout our history, one figure has lurked in the darkness of our collective hearts, haunted our nightmares, fired our imagination and fed our curiosity. For many of us, our first encounter with the creature known as a vampire was through the writing of Bram Stoker, or perhaps through Hollywood’s later interpretation of his horror classic Dracula, but this was written just over a century ago, and itself was partially based on a person who existed, who lived four hundred years previous to that.