Emergence of a Kingdom: From Britannia to England

It was under the Anglo-Saxons that England was born, as various chieftains claimed areas of the country and renamed them, giving rise to the first English kingdoms, the names of many of which survive today in English counties.

The Kingdom of Kent

It might be hard for English people to contemplate a small, market county like the so-called “Garden of England” forming the first proper post-Roman settlement in the country, but it is said to have been the first real English kingdom. Settled by two of the very first Saxon chieftains, Hengist and Horsa, two brothers who, finding their native Germany a little overrun with warlords and would-be kings, answered the call in 449 or 450 from Britain for assistance against the marauding Picts and Scots. Warriors born, the Saxons were easily able to defeat the northern invaders, bringing 1,600 men with them. This however turned out to be a two-edged sword, and the Britons soon had reason to regret having sought help from abroad.

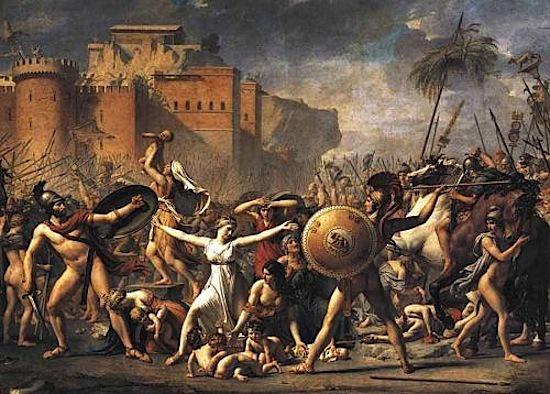

The Picts and Scots had been so easy to defeat, and yet the Britons so unable to fight them before the arrival of the Saxons, that Hengist and Horsa looked at each other, looked at England, nodded and said “We’ll have some of that” and proceeded to relay details of how puny and ripe for conquest these Britons were. So in the event, Britain swapped one occupying force for another, and the Saxons came over in their droves. They were clever though, careful not to reveal their true intentions at once; coming as saviours, defenders, paid mercenaries to protect the Britons from the wild Scots, they quickly found a way to quarrel with their erstwhile allies, claiming they had not been paid, and made alliances with the far more warlike Picts and Scots, joining them in oppression of the Britons.

Vortigern

The man who had inadvertently opened the door to invaders was the so-called King of Britain, Vortigern. He does not seem to have been overly popular, accused of incest - he is said to have had a son by his own daughter - faithlessness (though that might be due to his being essentially tricked by Hengist and Horsa) and, well, unlucky, which would be for the same reason I assume. He is linked to the myth of Dinas Emrys, recounted in another of my journals, which states that when a great lord (presumably meant to be him) wished to build his castle at this rocky hillock but it kept collapsing, Merlin (yeah, that’s how much we can rely on this tale - a fictional wizard. But it gets better…) advised him to have the foundations excavated, and they found two dragons asleep there, one red, one white. When the dragons were disturbed from their sleep they fought, the white triumphing, showing that England, the white dragon, would prevail against the red one of Wales.

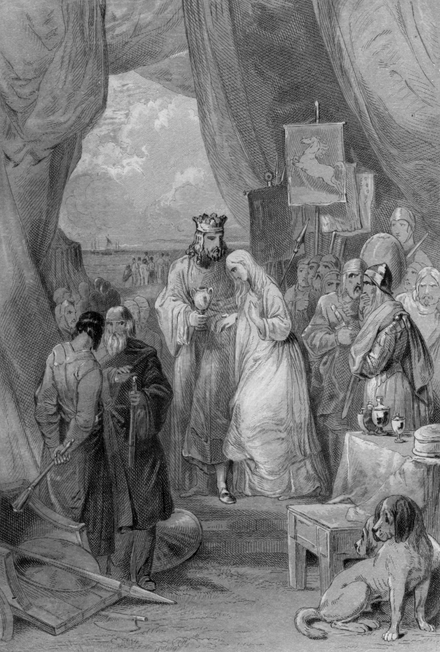

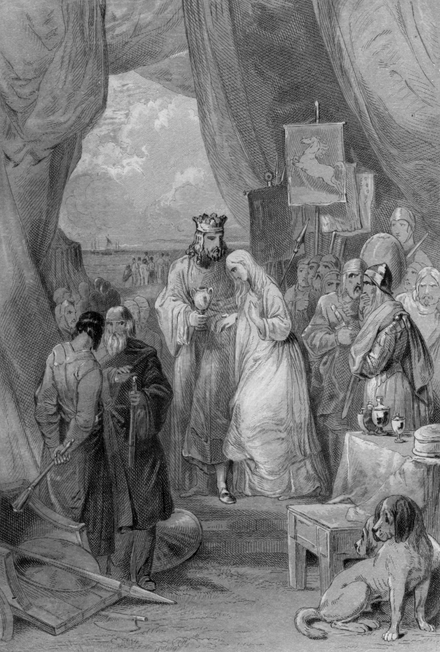

Vortigern is supposed to have married Hengest’s daughter, Rowena, giving him most of Kent in exchange (hope she was worth it!) and is said to have perished in “fire from heaven” brought down by the prayers of the monk Germanus (later Saint Germanus) of Auxerre, because sure why not? I imagine incest doesn’t go down too well with holy men, but as usual there’s no real way to verify these things, and he could have been hit by lightning, or died by the sword, or who knows? Nobody seems to have a good word for the guy though. Here’s what the foremost English historian of the twelfth century, William of Malmesbury, had to say about the first King of the Britons:

At this time Vortigern was King of Britain; a man calculated neither for the field nor the council, but wholly given up to the lusts of the flesh, the slave of every vice: a character of insatiable avarice, ungovernable pride, and polluted by his lusts. To complete the picture, he had defiled his own daughter, who was lured to the participation of such a crime by the hope of sharing his kingdom, and she had borne him a son. Regardless of his treasures at this dreadful juncture, and wasting the resources of the kingdom in riotous living, he was awake only to the blandishments of abandoned women.

I guess the Britons were still getting the hang of this king lark, but it seems odd that Vortigern was king, then succeeded by his son Vortimer (sounds like something out of Harry Potter, doesn’t it?) and when he was killed, dad snatched back the throne. I’ve never heard before of a line of royal re-succession, but that seems to be how they did it back then. Not that it mattered much, as Vortigern was defeated and replaced by Hengist, the throne (I guess basically of Kent) passing from father to son to father to father-in-law. Hey, there are even historians who think the name Vortigern doesn’t even refer to an actual individual, but stands as a sort of honorific or title. If he was real, I bet he’s rolling in his grave now. Well, rattling. Well, probably gone to dust by now. But I bet those dust particles are agitated.

Horsa didn’t last too long in merry old England, going down at the Battle of Aylesford (455), as related in the ninth-century Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: This year Hengest and Horsa fought with Wurtgern the king on the spot that is called Aylesford. His brother Horsa being there slain, Hengest afterwards took to the kingdom with his son Esc.

Press escape, huh? Sorry. Hengist is said then to have enlisted help from Saxony from his son, Octa (no, as far as I know he only had the two arms) who settled in Northumberland while Hengist ravaged the southeast, sparing “neither age nor condition nor sex”, which I think we can take to mean men, women and children, old and young, sick and well. He established the Kingdom of Kent, comprising Middlesex, Essex and parts of Surrey, and fixed his royal seat at Canterbury, from where he ruled for forty years until his death in 488 or thereabouts.

News of his success soon spread back home, and the Saxons, Angles and Jutes - all more or less the same and going under the one title of either Saxons or Angles - began arriving in numbers. The next kingdom to be set up was that of South Saxony. The Angles were so eager to come to Britain that they all did, leaving their country all but deserted and settling in (anyone?) Anglia, as well as Northumbria and Mercia.

Esc seems not to have been the greatest of kings, nothing like his father anyhow, and under his son Octa part of Kent was lost, taken or acceded to the East Saxons, who took Middlesex and Essex and formed the kingdom of East Saxon, or Essex. To some degree, under successive kings it seems that Kent could indeed have been called “the sleeping kingdom”. Esc’s son reigned for twenty-two years but seems to have done nothing of note, while his son reigned for ten years less but did as much, or as little, all leading up to AEthelbert, who appears to have been the first king of Kent to actually get his arse off the throne and do something for his kingdom.

What this was initially was to make war upon Ceawlin, king of Wessex, in 568, but his army was defeated and he retreated home to Kent. He then had to acknowledge Ceawlin’s authority over not only his but all the Saxon kingdoms, affording him the title of bretwalda, or Britain-ruler. Later (it isn’t clear when) he led the armies of other Saxon states (again, no information but we can assume East Anglia and Sussex were part of his “association”, as it is described) and this time Ceawilin was defeated, Aethelbert taking the title and also helping himself to the throne of Mercia. Aware that his allies might turn against him though, he cleverly returned the Mercian throne to Webba, son of its founder, Crida, but more or less as a puppet king.

More to the point, he almost single-handed converted his people to Christianity. This was due to several factors. The Saxons were a warrior people, loyal to their god Woden, god of war, and Thor, god of thunder, hoping to win valour in battle and enter Valhalla. But as their enemies diminished (despite still regional skirmishes, battles and even small wars among the kingdoms) and the Saxons began to settle down, like the Vikings who would follow them in three or four centuries’ time, and consider more the benefits of farming and commerce than war and plunder, the idea of paying homage to a god of blood and violence began to appeal less. Also, their people back home had mostly already been converted by missionaries sent out from Ireland and Rome, and they might have felt sort of like the poor relations or the backwards brothers in clinging to old, outmoded beliefs. Maybe it was time to change.

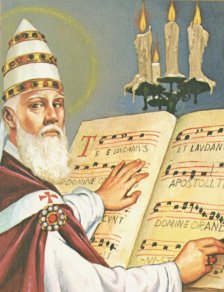

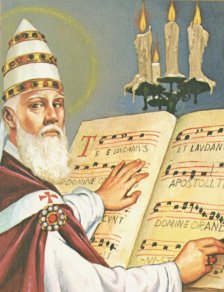

There is also the story told of a kind of epiphany had by the Pope: “Gregory, named the Great, then Roman pontiff, began to entertain hopes of effecting a project which he himself, before he mounted the papal throne, had once embraced, of converting the British Saxons.

It happened, that this prelate, at that time in a private station, had observed in the market-place of Rome some Saxon youth exposed to sale, whom the Roman merchants, in their trading voyages to Britain, had bought of their mercenary parents. Struck with the beauty of their fair complexions and blooming countenances, Gregory asked to what country they belonged; and being told they were Angles, he replied, that they ought more properly to be denominated angels: It were a pity that the Prince of Darkness should enjoy so fair a prey, and that so beautiful a frontispiece should cover a mind destitute of internal grace and righteousness. Enquiring farther concerning the name of their province, he was informed, that it was Deïri, a district of Northumberland: Deïri! replied he, that is good! They are called to the mercy of God from his anger, De ira. But what is the name of the king of that province? He was told it was Aella or Alla". Alleluiah!" cried he: “We must endeavour, that the praises of God be sung in their country.”

Moved by these allusions, which appeared to him so happy, he determined to undertake, himself, a mission into Britain; and having obtained the Pope’s approbation, he prepared for that perilous journey: But his popularity at home was so great, that the Romans, unwilling to expose him to such dangers, opposed his design; and he was obliged for the present to lay aside all farther thoughts of executing that pious purpose.

Well, you have to admire the old guy’s cheek, making so much out of so little. Had it not been for those pesky Romans though (what did they ever do for us?) he probably would have been on the next galley or trireme or whatever, on his way to England, accompanied by a heavenly host, or at least a whole shitload of monks, bishops, priests and clerics. Not sure what kind of reception he would have got in then-Pagan Northumberland though!

Instead he chose his shock-troops, led by a Roman monk called Augustine, later to be canonised as Saint Augustine, but they were so fearful of the Pagans that they decided to layover in France for a while, and sent their leader back to the Pope asking if he was sure it was safe. Gregory basically chased them out of France with a broom, telling them to go do their job, and duly admonished they landed in England and met with Aethelbert. Their first impression must have been “damn rainy here” (though being holy men and not wanting to profane the name of the Lord they probably said something like “Has God not in his wisdom blessed this land with an abundance of his bounteous rain, that the crops may grow and the land be fertile?” Possibly adding sotto voce, “but thank Christ he hasn’t seen fit to endow our eternal land with the same gifts, as I like to take the air in the gardens of my Italian monasteries, and there’s nothing as certain to ruin a nice walk as a heavy fucking shower of rain, beg your pardon Lord, pardon my English.” ) That was a long bracket! Get used it it: I do that all the time.

Their second though may have been “this isn’t such a bad place is it?” and when monsters completely failed to rise up out of the ground and swallow them whole, fire did not rain down on them (though rain surely did) and the approaching contingent of Saxons, led by Aethelbert, were only normal size and had the standard number of heads each, they must have breathed a sigh of relief. Aethelbert, for his part, was still suspicious, expecting magic and sorcery (being an ignorant pagan and all) and so had ensured he met the Christian missionaries in the open air, as if that somehow negated any magic they were perceived to have.

Finding, possibly to his own relief, that these unbelievers also possessed only the regulation number of heads and did not try to suck the soul from his living body, Aethelbert may have grumbled “Look, I still don’t know about you guys… Hey!” Turning on one of them fiercely who had begun muttering a prayer. “No trying to convert me when I’m not looking!” And back to Augustine as their leader “I suppose you can have the Isle of Thanet. It’s not very big and we’re not doing anything with it at the moment. Kind of a dumping ground for old weapons and odds and sods. Kick back there and we’ll see how you go. But no,” again turning with a fierce eye, “sneaky trying to steal my soul behind my back, you!” I’m sure Bede himself would back up such a conversation. Oh no wait, he’s dust now. Oh well, you’ll just have to take my word for it I guess.