I have posted this before, but I make no apologies for doing so again.

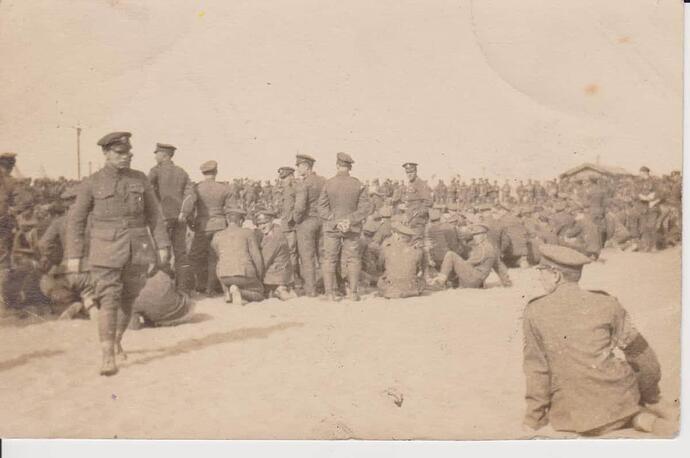

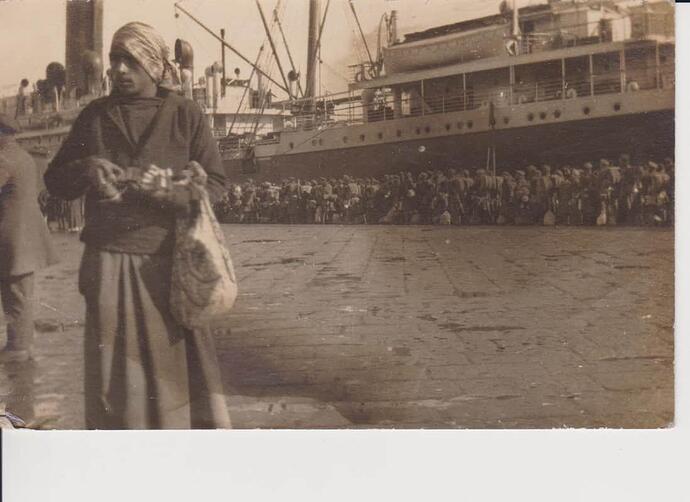

The men from my Mum’s side of the family were farming stock from the West Country of England, and many served in West Country regiments during WW1. They didn’t all come home.

The men from my Dad’s side of the family were builders and labourers. Two of them were pacifists. My great uncle Vic refused to fight, yet won a medal for bravery as a stretcher bearer. My granddad was a Quaker, yet I remember seeing a photo’ of him in an army uniform. Perhaps he too was a non-fighting hero, but nobody in our family ever spoke of The Great War.

Thanks to an old photo album, old letters, and the internet, I have pieced together some of their stories.

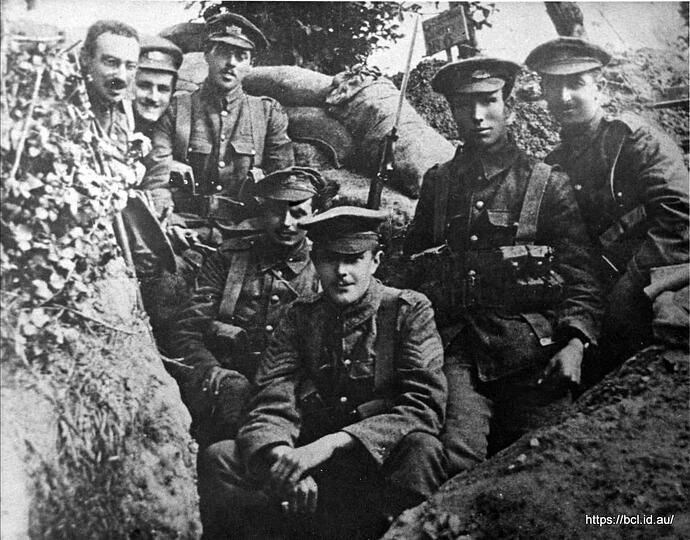

My great uncle William, Somerset Light Infantry, aged eighteen. Taken before he went to war. He looks nervous.

Aged nineteen, having been wounded and sent back to England to recover. Battle hardened and confident he looks now.

He died at Passchendaele, aged twenty, and has no known grave.

Today, I shall cry

Khaki cloth and Sam Brown belt,

Puttees caked in mud,

Men and shrapnel scream through the air,

The stench of death and blood.

Poised upon the firing step,

Where flowers once grew wild,

An old man’s eyes wearily look out,

From a soldier who is still but a child.

Wounded once, yet returned to battle,

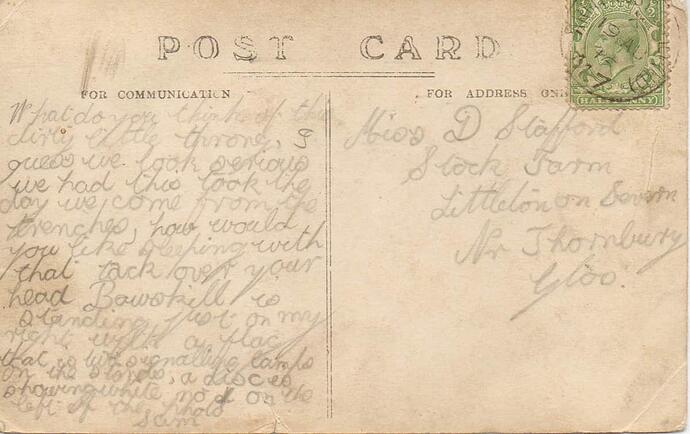

Post cards home that he wrote,

Old enough to die in battle,

Yet not old enough to vote.

His brothers never speak of horrors seen,

Memories of their young brother grow dim,

Back home on the family farm,

No known grave to visit him.

His face upon an old postcard,

“By ‘eck Ma, I do look grim.”

Next the clock on mantlepiece,

Only my family remember him.

All across this land of ours,

Flags at half-mast fly,

Poppy red upon my breast,

For him today, I shall cry

The Blacksmith’s Song

The wind soughs through a broken window,

Cobwebs wave in the gentle breeze,

Dust motes float and sparkle in the air,

As white-hot iron once gleamed.

Birds fly in and out,

A missing roof tile their front door,

Mice on the floor sharing their world,

Scurrying and flapping adding soft sounds.

Tools hang lifeless on nails in old dry wood,

Tongs for holding, giant pliers for twisting,

Swages, sledges, and wedges,

Waiting for the hand that will never come.

Bars of wrought iron,

A broken iron gate awaiting repair,

A pile of coke, with shovel standing by,

Like a soldier waiting for orders it will never hear.

Leather bellows, split and cracked,

Lifeless like the hearth,

The fierce roar silenced,

No one now to stoke the fire.

The anvil lies cold and dead,

Like the man who once worked it,

His name on a plaque in a foreign land,

Along with the words, “No known grave.”

The forge now lies silent,

But if you listen hard,

You might hear a faint sound,

Like a music box playing in the next room.

If you listen harder still,

You might just hear the Blacksmith’s song,

Ringing clear and true like a bell,

The ringing song of hammer on iron.

Red for the blood that was spilled.

Black for mourning of those that died.

Green for the new growth followed on the battlefields after the fighting stopped.

The leaf set at the eleven o’clock position for the time when the guns fell silent.

More to follow.