Did she keep a straight face?

Nah. She’s got to squint to see it ![]()

I thought I knew the name.I had a framed print of that but had to leave it behind. ![]()

Well actually it put her in between a rock and a hard place…

How could she argue if I was her first love?

![]()

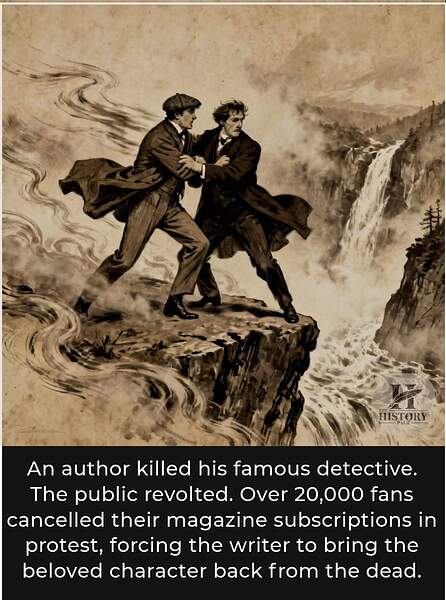

In 1893, when author Arthur Conan Doyle killed off Sherlock Holmes, the public outcry was so immense that many called it a ‘literary crime.’

Doyle wrote “The Final Problem,” a story where Holmes and his nemesis, Professor Moriarty, fall to their deaths at the Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland.

He wanted to end the series for a simple reason. He felt the detective stories were a distraction from what he saw as his more important work, historical novels.

The public did not agree. The reaction was immediate and passionate.

Readers of The Strand Magazine, where the stories were published, sent a flood of angry letters. An estimated 20,000 people cancelled their subscriptions in protest.

Legends from the time say that young men in London were so distraught they wore black mourning bands on their arms for the fictional detective. Even Doyle’s own mother apparently wrote to him, saying “You can’t. You mustn’t. You won’t.”

Under immense pressure, Doyle eventually gave in. In 1901, he published “The Hound of the Baskervilles,” a story set before Holmes’s death.

Then, in 1903, he fully revived the character in “The Adventure of the Empty House,” revealing that Holmes had faked his own death to escape his enemies.

The public’s love for the character was so strong it literally brought him back from the grave, cementing Sherlock Holmes as one of the most enduring figures in all of literature.

Thanks Minx, I knew feelings were strong about his death, but not that strong…

It seems you can’t keep a good detective down…It’s just ‘Elementary’

![]()

When I was at Uni, I went to see a play which was the character Dr Watson telling stories around the time of the disappearance on Holmes & Moriarty. It was one actor, with the stage set up as 221B Bakers Street. It was so good, I went to watch it a couple more times.

I know a very rude joke about the “elementary” part of that. But it’s somewhat homophobic and I don’t think the boss would really allow it. Fair enough.

![]() Did you know Japanese curry isn’t actually Japanese? This incredible culinary journey will blow your mind! The dish that millions of Japanese families eat weekly has a shocking origin story that spans three continents and involves the British Empire.

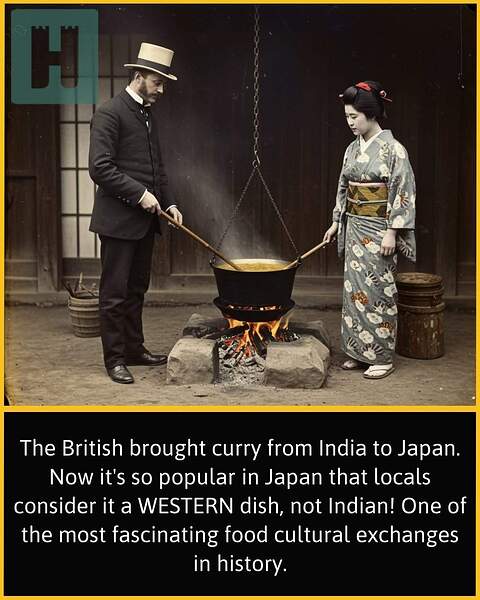

Did you know Japanese curry isn’t actually Japanese? This incredible culinary journey will blow your mind! The dish that millions of Japanese families eat weekly has a shocking origin story that spans three continents and involves the British Empire.

This is one of history’s most fascinating examples of cultural culinary exchange! When Japan ended its isolationist sakoku policy in 1854, the country opened up to Western influence and trade. British merchants and diplomats, who had acquired a taste for curry during their time in colonial India, introduced the spiced dish to Japan in the late 1800s.

What makes this story incredible is how curry evolved in Japan. The Japanese adapted the recipe to local tastes, making it milder, thicker, and sweeter than traditional Indian curry. They added ingredients like potatoes, carrots, and onions, creating what became known as ‘kare raisu’ (curry rice). By the early 1900s, curry had become so integrated into Japanese cuisine that it was served in school lunches and naval ships.

The most ironic twist? Because curry came to Japan through British channels during the Meiji period’s Westernization movement, Japanese people began categorizing it as ‘yoshoku’ or Western-style cuisine, completely separate from its Indian origins. Today, curry is one of Japan’s most popular dishes, with the average Japanese person eating it 84 times per year, yet most still consider it Western food rather than Indian.

Sources: ‘The Curry Chronicles’ by Lizzie Collingham, ‘Japanese Foodways Past and Present’ edited by Eric C. Rath and Stephanie Assmann, and research from the Japanese Curry Association historical archives.

An unfortunate name when discussing curry…

![]()

Interesting post though Minx…

![]()

Wasn’t curry invented in Birmingham?

Johnny Cash visited Brums Balti Triangle, and left with a Ring of Fire.

![]() Sharp, very sharp … you don’t miss a thing do you Foxy!

Sharp, very sharp … you don’t miss a thing do you Foxy!

He IS a sharp cookie !

In 1946, a frustrated mother cut up her shower curtain and accidentally invented something that would change parenthood forever. Marion Donovan was exhausted. Not the kind of tired that comes from a hard day—the kind that accumulates from endless, repetitive labor that no one sees, acknowledges, or thinks to improve.

She had two young children, and like every mother of her era, she was drowning in laundry. Cloth diapers were all that existed. They leaked constantly, soaking through clothing, bedding, and furniture. Babies developed rashes from sitting in dampness. Mothers spent hours every single day washing, boiling, and drying stacks of soiled diapers, only to start again the next morning. Everyone simply accepted this as "how things were. "But Marion looked at the problem and thought: Why?

One night, instead of resigning herself to another load of laundry, she grabbed a shower curtain from her bathroom. She sat down at her sewing machine and began cutting and stitching, creating a waterproof cover that could go over cloth diapers. But here was her genius: unlike rubber pants that trapped moisture and caused rashes, her design had snap fasteners instead of pins (safer) and allowed air circulation (healthier for baby’s skin).She called it “The Boater” because it kept babies afloat and dry.

Marion knew immediately she’d created something transformative. This wasn’t just about keeping babies dry—it was about giving mothers back hours of their day. It was about dignity. About acknowledging that women’s time and sanity mattered. She tried to sell her invention to manufacturers. Their response was unanimous and dismissive: unnecessary. Mothers don’t need this. They’ve managed for centuries with cloth diapers. Why would they want something different?

But Marion understood something those businessmen didn’t: just because women had endured something for centuries didn’t mean they should have to continue enduring it. She refused to give up. If manufacturers wouldn’t help her, she’d do it herself. She took The Boater to Saks Fifth Avenue in New York, convinced them to carry it, and watched as it flew off the shelves. Mothers who tried it once became loyal customers instantly. Word spread not through advertising, but through the exhausted, grateful whispers of women who finally had a solution to a problem they’d been told didn’t matter. In 1951, Marion patented The Boater.

That same year, she sold the patent to Ke ko Corporation for one million dollars—approximately $12 million in today’s money. She wasn’t just an inventor. She was a savvy businesswoman who understood the value of what she’d created. But Marion still wasn’t satisfied. She looked at the waterproof cover and thought: We can do better. She began designing a fully disposable diaper—one that parents wouldn’t need to wash, dry, pin, or cover. They could simply throw it away and move on with their day. It was revolutionary. It was practical. It was, to Marion, obvious. Businessmen called it “absurd.” They insisted mothers would never throw diapers away, that it was wasteful, impractical, and would never catch on. They fundamentally misunderstood what Marion was actually inventing: not just a product, but freedom. Time. The ability to be present with your child instead of being enslaved to endless laundry.

Though manufacturers rejected her disposable diaper design in the 1950s, her concept laid critical groundwork. Years later, when Victor Mills developed Pampers in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the disposable diaper finally entered mass production. Marion’s vision had been vindicated—the industry had just needed time to catch up to her thinking. Marion didn’t stop inventing.

Over her lifetime, she held more than twenty patents for innovations large and small: a dental floss dispenser, a better facial tissue box, closet organizers, and countless other solutions to everyday problems that most people never thought to fix. She wasn’t inventing for glory or fame. She was inventing because she noticed problems and refused to accept them as unchangeable. Because she believed that making life easier—especially for women—was worth pursuing, even when others dismissed it as trivial.

Marion Donovan died in 2014 at the age of 92. By then, the world she’d helped create was almost unrecognizable from the one she’d entered. Disposable diapers were a multi-billion-dollar global industry. Millions of parents had hours of freedom she’d envisioned decades earlier. The endless cycle of diaper laundry had been broken. Her story matters not just because she invented something useful, but because she represents every person—especially every woman—who looked at accepted burdens and asked: "Why do we have to live this way? "Innovation isn’t always about grand technological leaps. Sometimes it’s about noticing the small, daily struggles that shape people’s lives and having the audacity to believe those struggles deserve solutions.

Marion Donovan saw invisible labor and made it visible. She saw exhausted mothers and gave them time. She saw an accepted burden and refused to accept it. And in doing so, she proved that changing the world doesn’t always require a laboratory or a fortune—sometimes it just requires a shower curtain, a sewing machine, and the stubborn belief that life can be better.

Truly “necessity is the mother of invention”

I wonder why Brits call them nappies?

Wonder no more…

“Nappy” is short for napkin, the older British term for a cloth used to wrap babies before disposable diapers existed.

In the mid-20th century, British English kept nappy while American English adopted diaper, a word that originally referred to a patterned fabric used for the same purpose.

So both terms mean the same thing—just different linguistic evolutions:

• British English: nappy (from napkin)

• American English: diaper (from diaper cloth)

In 2015 a new species of tarantula was found close to Fulsom Prison in California. Tarantulas are sexually dimorphic. And in the new species, the males are largely dressed in black. Thus, the new species was named Aphonopelma jonnycashi.

Johnny Cache, hid his light under a bushel!

Historically, the USA are not very good at generating codewords. Take Gulf War 1 for instance.

The UK codename was Operation Granby.

The US codename was Desert Storm. Oh what a giveaway.

The five D-Day invasion beaches were: -

Gold

Sword

Juno

Omaha

Utah

Can you spot which ones were generated by the US?

The UK invasion beaches were named after fish; Gold(fish) and Sword(fish), and the Canadian beach was originally going to be called Jelly(fish).

The Canadian forces quite rightly objected to storming Jelly beach. Instead, they chose Juno, the mother of Mars, the Roman god of war.

The codename Star(fish) couldn’t be used as it was already in use. Decoy dummy airfields were called Q-Sites, and one particular decoy dummy town was called Starfish. This name stuck, so all dummy towns became known as Starfish sites.