Epilogue II: Four Grey Fields: The End of Ireland?

No single event in Irish history has had such a devastating effect on the country. Not even the ravages of the Black Death five hundred years earlier could come so close to destroying our small island. During the Great Famine, over a million people emigrated and never came back, either dying on the voyage that took them away from their native land, or reaching their destination and, again, either dying there or prospering, building a new life in a new land. Of those who remained, it’s estimated about the same number perished, from hunger, exposure, infirmity or by falling prey to any of the many diseases mentioned above. With a population calculated at the time as being in the region of almost nine million prior to the arrival of the blight and the onset of the Famine, that means almost a quarter of the people in Ireland left or died by the time it was over.

This had a huge and lasting effect on the country, which still today only numbers its citizens at around five or six million (seven including Northern Ireland). Had the Famine not occurred, or had it been dealt with properly, it seems likely that we would now be approaching the eleven or twelve million mark. This is probably, to be fair, far too large for such a small island, so in some very cynical and cold way you could look on the Great Famine as having been a sort of forced depopulation or reduction of the numbers living in Ireland. But due to the massive emigration from necessity and to save lives, the idea soon took hold and even now, when the only real factors driving it are financial and social prospects, when it is certainly more voluntary to leave the country than it was then (and a lot safer) Ireland has embraced emigration, with mostly younger, skilled people seeking an outlet for their talents - and the appropriate reward in monetary and promotional terms - abroad, to the extent that there used to be a funny poster on sale here with a map of the country and the request “would the last person to leave Ireland please turn out the lights?”

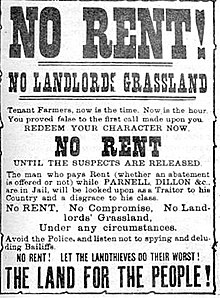

Another major effect the Famine had was to lead to the ending of smallholder leases on land, as landlords, many broken by the loss of their tenants and the cost of the Famine to them (oh boo hoo indeed!) gave up their lands and were replaced by Catholic farmers, who bought up the land and used it for pastureland, a practice that continues today, and has led to farmers becoming some of the richest men in Ireland (though they’ll tell you differently). Despite the abortive and mostly laughable “rising” of the Young Ireland movement spoken of briefly earlier, the country was so drained and exhausted that all thoughts of rebellion or independence died for about twenty years. There simply was no appetite (pun intended) for facing up to the almost-architects of the Great Famine, no strength and no spirit; the country was broken, though of course it would not remain so. For a long time, all people wanted to do was get back to some sort of normal, some sort of life, and give thanks that they had survived. Nobody wanted to push God on this one.

So despite 1848 being known across Europe as the “year of revolutions”, with particularly the Paris revolt that returned Napoleon to the head of the Second French Republic, and notwithstanding the efforts of Thomas Davis and Young Ireland, the country had been battered to its knees and had no fight left in it, and revolution, rebellion and rising all passed Ireland by. It would take the rise of the Fenians in 1860 before Ireland would again be able to stand up to its auld enemy and gird itself for battle. Needless to say, spoiler alert, such attempts would fail. It would in fact take another half a century before Ireland would finally be free, and even then, well, we’ll see when we get there, but let me just say that the course of independence never ran smoothly, nor did it with Irish freedom.

Politically, one thing the Famine did prove, even if the Irish were too bone-weary and heartsick to address it, was that the Act of Union was pure bollocks. The idea had been that Ireland would, as part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, enjoy the same patronage and protection England, Scotland and Wales did, but of course the cold and uncaring response to the Famine showed this was nowhere near the case. Ireland was treated more as a troublesome colony that had been reined in, in the same way America could not be, and was once again firmly ground under the heel of the British boot. Very little, as we have seen, was done to help the “new recruit”, and in fact largely the problems of Ireland were ignored, scorned, derided and pushed to one side. So though the body may have been weak, the spirit, in some ways, was willing, and the Irish would not forget the way they had been treated. Nationalist fervour, only held for now at arm’s length, would soon return with renewed fury.

Just let them catch their breath first, all right?

Another, sadder effect of the aftermath of the Famine was that many young girls who had been lucky enough to survive were now orphans and had no visible means of support. This led to the rise of prostitution in Ireland. Of course, no doubt there had been ladies of the night in the country before, but now once-respectable women were forced out onto the street in order to simply earn enough to feed their families. One of the major ports of call, so to speak, for these orphaned girls was Curragh Barracks in Co. Kildare. With a permanent British military presence established there, and soldiers always horny, the business was brisk for them, but because they were not allowed stay in the barracks they were reduced to sleeping in and around its environs, in bushes and ditches, leading to their becoming known as “the wrens of the Curragh”.

In general, it seems the army treated the women well, allowing them to buy supplies at the market and making sure they had water, and some of them even married, though due to army regulations they were not allowed to live at the base. Locally, they were shunned and called “morally repugnant” and such terms by people who believed they brought disease and were thieves, so I must say it’s certainly nice to see how shattered Ireland banded together in a common cause to help those who had suffered through the worst humanitarian disaster in their living memory. Catholic Ireland my arse. It wasn’t as if these women chose to be sex workers; they simply had no other choice.

Although not the final death knell for the Irish language, emigration and the death of many native Irish speakers (the effects of the Famine being of course hardest felt in the poorer, more rural and therefore more Irish-speaking areas of the country) certainly hastened its demise. Although a sort of reverse reaction occurred in the countries to which the emigrants moved, especially in America, where a reawakened interest in all things Irish, including the language, grew as more emigrants arrived, back home the language of choice was quickly becoming English, and today, as already mentioned, few if any people can speak proper Irish, nor really want to.

Another thing the emigrants exported with themselves was the idea of nationalism, and independence for the country they had left behind, leading to a growing groundswell of support for the “Irish cause” which would lead to finance for and interest in Irish republican paramilitary forces like the IRB, the Fenians and later the IRA. As some Irish immigrants rose to positions of power and standing in the USA, they would use their new influence to do all they could to support and endorse and help to bankroll the rebellions and risings against the British back home.

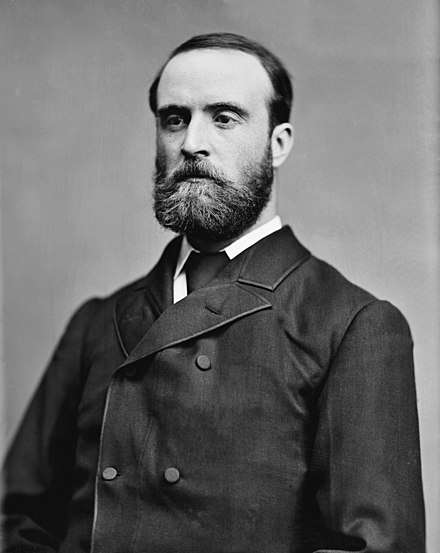

While it may certainly be a biased view - how could any contemporary source be otherwise, on one side or the other? - the final word should perhaps be left to the man whose quote opened this chapter, writer John Mitchell, editor of the nationalist paper The Nation, which would inspire the creation of the Fenian movement twenty years later. You can certainly hear, in his damning words, the voice of every Irish person who died needlessly, whether they dropped from starvation or perished on one of the coffin ships, or in a foreign land, far from home. More than perhaps anything they ever did, even the outrages perpetrated by Cromwell or the dissolution of the monasteries by King Henry VIII, Irish people look to the brutally indifferent response by the British government to the Great Famine to fuel and keep alive their hatred of the auld enemy.

”I have called it an artificial famine: that is to say, it was a famine which desolated a rich and fertile island that produced every year abundance and superabundance to sustain all her people and many more. The English, indeed, call the famine a “dispensation of Providence”; and ascribe it entirely to the blight on potatoes. But potatoes failed in like manner all over Europe, yet there was no famine save in Ireland. The British account of the matter, then, is first, a fraud; second, a blasphemy. The Almighty, indeed, sent the potato blight, but the English created the famine.”

No apology has ever been forthcoming from the British government, even now, almost 150 years later. In 1997 it seemed Tony Blair’s government had finally grasped the nettle, when his statement was read out by Gabriel Byrne at a Famine commemoration event. It said ”“those who governed in London at the time failed their people through standing by while a crop failure turned into a massive human tragedy”. The sincerity of the message was however dampened when, in 2021, it was confirmed that Blair had not written, nor approved the message, and it had come from his private secretary, as a personal gesture. That’s all well and good, but it’s the head of state - the real head of state - we want the apology from, not some secretary, flunky or underling.

Even now, in these enlightened times, when relations between Ireland and Britain seem to be at the strongest they ever have been, even now, it appears we are still seen as inferior, no excuse or apology needed, no responsibility taken, and quite possibly, the ghosts of two million Irish cry out for reparations which will never come, and two simple words which will never form on the lips of the leader of the British government: “We’re sorry”.