Chapter VI: The Book of Invasions, Part Four: Terra Incognita, Treachery and The Fall of Ireland

Timeline: 1512-1607

Papal Enemy Number One: Henry VIII and the English Reformation

Having, as I mentioned earlier, only won our independence in 1923, the history and destiny of Ireland has been throughout our long history controlled by outside forces, most notably of course by England, who held sway over us for over eight hundred years. It’s therefore necessary, I feel, to look at the major figures who orchestrated the invasion, occupation and governance of Ireland, and as the timeline progresses this is what I will be doing.

Many kings and queens of England of course had a hand in the subjugation of Ireland, and we’ve already heard about Henry VII and the Normans, but to my mind there’s one figure who typifies the antagonism that would come to define the relationship between Irish and English, which would lead to a schism in Irish belief, and to the very sectarianism that plagues our island even today.

When the Celts were under the sway of the Druids, they worshipped gods, but more importantly goddesses; Ireland, though controlled by a patriarchy, was a matriarchal theocracy, or something. Goddesses were big in Ireland, is what I mean, and through the intercession of the Druids laid down the laws by which the Celts lived. When the druids, along with their deities, were driven out of Ireland, the Irish looked to a new mother figure: the Catholic Church. She protected and nurtured them all through the Dark Ages, even into Tudor times, and when one king took on the Pope, it spelled trouble for Ireland, and began a hated and enmity that has existed to this day.

Henry VIII (1491-1547)

Even those of you with zero interest in history know Henry VIII, if only from the famous portrait that shows him as a fat, lame corpulent man scowling out of the picture. Of course, he wasn’t always like this - witness his many marriages, few if any ones of convenience - but this is the popular image we have left of him, just as Shakespeare was also obviously young and handsome at one point, but we now picture him as a balding, oldish man in a high Elizabethan ruff. If we know Henry for anything though, it’s likely one of two things (or both): firstly, for having six wives, two of whom were beheaded at his command, and secondly for his spat with the Pope and the formation of the Church of England. None of this would of course endear him to the fiercely Catholic Irish, and his actions during his reign would not help that cause. For those who may have the sketchiest knowledge of one of the most famous and written about English kings, here’s a very quick potted history.

Only one of four to survive from the six children born to his father, Henry VII, Henry was already appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland at the tender age of three. What this actually meant was that his father, Henry VII, retained control over Ireland and no other noble could request or even demand the position. Nevertheless, though it may have been nothing more than a nominal or symbolic position, the fact remains that from his infancy right through to his death, King Henry VIII’s fate would be inextricably and irrevocably linked with that of Ireland. The youngest of the surviving royal children, he was never expected to ascend to the throne, this honour to befall his elder brother Arthur. However Arthur did not reach his sixteenth birthday, dying before he could claim his heritage, and as the two other children were girls, it was Henry who became heir to the throne of England.

Catherine of Aragon

When his father died in 1507 Henry realised his destiny, taking the wife, well, widow, of his late brother Arthur, Catherine, youngest child of the rulers of two powerful Spanish kingdoms, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile, but when she failed to provide him a son (all of her children, boys and girls, being stillborn, and the last one to survive being a girl) he decided to look further afield. Having had an affair with Catherine’s lady-in-waiting, Mary Boleyn, he then took a fancy to her sister. But Anne was not content to be a mere king’s mistress, and demanded marriage. This meant that Henry’s marriage to Catherine had to be annulled, and the only one who could do that was the Pope. There was, however, a problem.

Catherine was aunt to one of the most powerful Spanish rulers, the Holy Roman Emperor himself, Charles V, and Pope Clement VII, reluctant to get on his bad side by sanctioning what would be seen as the public dishonour of Catherine, demurred. Annoyed at this seeming refusal (which it pretty much was) to grant him the freedom to marry again, Henry decided to dissolve the power of the Catholic Church in England, setting himself up as supreme head of the Church, and thereby making an enemy of the Pope. This is curious in a historical context, as the previous Pope, Leo X, had conferred upon Henry the title of “Defender of the Faith” for his defence of papal authority! I guess sentiments like that are fine as long as they fit in with your own requirements.

Henry married Anne Boleyn in 1533 (though technically she had been unofficial queen since 1531, Catherine having been banished from the royal apartments, stripped of her title and no longer recognised as the king’s consort) and she gave him one child. It was a girl, which was surely disappointing to Henry at the time, though she would grow up to become one of the greatest rulers England had ever seen. Elizabeth was born on September 7 1533, a mere three months after Anne had been officially crowned as Queen Consort. For his temerity in going against Rome and setting up the Church of England, Pope Clement excommunicated Henry. This meant he was forbidden to attend mass, have his sins forgiven and his soul was damned to Hell for eternity. Henry wasn’t worried.

He was worried, however, about the line of royal succession. If there was one duty a king took as seriously as protecting his realm it was securing an heir to continue his dynasty. Not for another six years would a woman sit on the English throne, the only one to ever do so up to that point, other than Matilda, whose monarchy is hotly disputed even now, the line of succession always falling to the male heir. If a king were to die without a son therefore, there would be no legitimate king, and infighting would result as those next in line to the throne would all vie for the position. This could lead to civil or even outright war, as in the War of the Roses, as already related, although the king in that case did have an heir, but he was allegedly murdered.

So producing a successor to his reign was of paramount importance to Henry, and while this was the task of the queen, if successive wives failed him then it would be hard to continue pointing the finger at the woman, and suspicion might fall upon the king himself. Apart from the ignominy of being talked of as impotent, the strategic and historical imperatives were clear here: die without an heir and risk plunging England into bloody conflict, in the process leaving her at the mercy of her enemies, who would surely capitalise on her weakness.

Henry’s desire to ditch Catherine and take up with Anne however was not purely motivated by regnal duty; he was also a randy old sod, and as king he could have as many mistresses as he liked, but any progeny from such unions would be illegitimate, and therefore ineligible for the throne. To produce a proper, legitimate heir who would be supported by all and whom the law would recognise, Henry had to have a son by his queen.

But that didn’t mean it had to be this queen.

When Anne failed to satisfy his need for an heir, Henry had - perhaps trumped-up - charges of infidelity and adultery levelled against her, branding her a traitor and allowing him to have her executed. He then moved on to Jane Seymour, whom he had been seeing more of (sorry) even as Anne Boleyn awaited her trial and execution. Jane finally gave him the heir he had craved, and which England needed, and Prince Edward was born on October 12 1537. However Henry’s joy was cut short as his wife and queen of only a year died twelve days later of complications from the birth. It could be said that though she was the wife who lasted the shortest time, she was also the most loyal, giving him his heir and also her life, though the latter hardly willingly.

Anne of Cleeves

For the first time since ascending the throne of England, Henry needed but did not necessarily desire a new wife, which is to say he was in mourning for Jane, not bored of or frustrated with her, but as king he knew he had to have a queen, and this time one was chosen for him - well, let’s say suggested to him: I doubt anyone ever told King Henry VIII what to do. But on the advice of Thomas Cromwell, he married Anne of Cleeves, who then became his fourth wife. But already Henry’s eye was wandering, and this time it fixed on a seventeen-year-old niece of the Duke of Norfolk, Catherine Howard, much to Cromwell’s annoyance, as her father was a political opponent of his. He was right to be worried, as on the very day of the king’s fifth marriage he was accused of treason and executed. No doubt the good Duke had a hand in that.

Catherine would not survive him long though. Embroiled in adulterous affairs, she was caught out and though Henry initially refused to believe his new wife had been unfaithful to him, he was forced to accept the evidence, especially when it came from her own mouth, and Catherine Howard became the second of Henry’s so-far five wives to literally lose her head over the king. His final marriage would see him attracted to yet another Catherine, this time Catherine Parr, who had already had three husbands before Henry. She helped him reconcile with his daughters Mary and Elizabeth, resulting in an Act of Parliament that allowed both the girls to join the royal line of succession, paving the way for England’s first two queens.

So that’s Henry VIII and his famous six wives, but why did the Irish hate him so? Well, clearly when you defied the authority of the Pope you were going to make no friends in a country that, while ruled by English nobles (Normans) was still staunchly and defiantly Catholic, and who after all wants to swear fealty to a heretic? But it wasn’t just that. Henry had demanded loyalty to the Crown from Ireland, and this put the Irish nobles in a very tough and unenviable position. Fiercely loyal to the Pope, they did not want to be seen to be going against the wishes of the Holy Father, but Rome was a long way away, much more distant than England, and when Henry declared that all of Ireland must follow “the English way”, including worship, he found stiff opposition from the Irish against his plans.

Here I want to pause for a moment, and explain in basic terms how the massive split occurred in the Catholic Church, how that affected Europe, Rome and later England, and by extension Ireland, and how it continues to do so even today, dividing our island along geographical as well as religious lines of orthodoxy, giving rise to conflict, hatred, prejudice and our own horrible version of holy war.

The Rise of Protestantism: Martin Luther goes head-to-head with the Pope

There can be no argument that in the time before, and even during the Renaissance, the Catholic Church was not only a major world power, almost the major world power, a huge player in politics, maker and breaker of kings, and the agency that called for retribution against the heathen with the Crusades, but one of the most corrupt organisations in the world. Successive popes set themselves up as kings, emperors or warlords (or all three), keeping standing armies and enriching their own coffers, more concerned with material wealth than spiritual salvation, while their priests and bishops preached exactly the opposite message to the faithful from the pulpits every Sunday.

A young German monk named Martin Luther had been watching all this misuse of power for some time, but the final straw for him came in 1516, when the Pope at the time, Leo X, sent an envoy to Germany to sell indulgences in order to finance the rebuilding of the church of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Indulgences were, essentially, get-out-of-jail-free cards for Christians, though scrub out the word free. For a payment, large or small depending on the sin to be expunged, penitents could purchase a letter signed by Leo which would then allow a soul held in Purgatory (transient state between Heaven and Hell) to be released into Heaven. Basically you were paying for the soul of your mother, father, child, wife, whoever, who had died, to be sprung from Limbo.

The phrase “As soon as the coin in the coffer rings,The soul from Purgatory springs” so enraged Luther that he wrote to the Pope, decrying the practice of indulgences, and asking, quite reasonably really, why a man so incredibly wealthy as Leo X, reckoned at the time to be one of the richest men in the world, if not the richest, had to rely on the contributions of the poor to rebuild a church when he had the money to do so out of his own pocket? Instead of answering this accusation, the Pope decided to brand Luther a heretic and excommunicated him, in the same way as he would deal with England’s upstart king a decade later.

But Luther would not be so easily silenced. He saw the rot in the Catholic Church, most especially at its venerated head, and the disrespect that the man supposedly chosen by God as His agent on Earth paid to the office, and he and his followers broke with Rome, splintering into their own religion, which though still Christian would be rabidly opposed to Catholicism. It was, of course, called Protestantism. As already noted, the later heretic King Henry VIII initially defended the Pope against this blasphemer, only to find himself, perhaps not allied with Luther’s ideals so much as using them for his own expediency, but certainly on the same side as the German reformer.

This of course put the king of England on a collision course, theologically and ideologically with the Irish, but it wasn’t just esoteric concerns that upset them. Having broken with Rome, Henry now felt entitled to break up the monasteries, which were of course run by Catholic monks and abbots, and seize their assets for the Crown. This became known as “the dissolution of the monasteries”, and this was bad enough, but, perhaps unsurprisingly, he then ordered the same fate for the monasteries in Ireland. These had existed, more or less unbothered by the Crown, for centuries, and had survived invasions both Viking and Norman. The dissolution of the monasteries was a direct and very public middle finger from England to Rome, and shocked and angered the Irish, who still considered themselves mostly the Pope’s subjects. Although the dissolution of the monasteries represented a seismic shift in English royal policies, Henry’s action was neither unprecedented nor unique throughout Europe.

As the rise of Protestantism and Anglicanism, both versions of Lutheran teachings, gripped Germany and expanded outside its borders to places such as Switzerland, Holland, Scotland and even fiercely Catholic France, the idea of monasteries was slowly being eroded. Monasteries were quintessentially a Catholic, or as some preferred to call them, papist idea, and those who no longer wanted anything to do with Rome wanted all trace of their power removed from their countries. In that context, then, it’s not at all to be wondered at that Henry wished to reinforce his own power as the new Supreme Head of the Church of England, and remove the agents of the Pope. Of course, the fact that these monasteries stood on choice land and contained valuable artifacts that could be sold, or melted down, and used to fill the king’s coffers, didn’t hurt either.

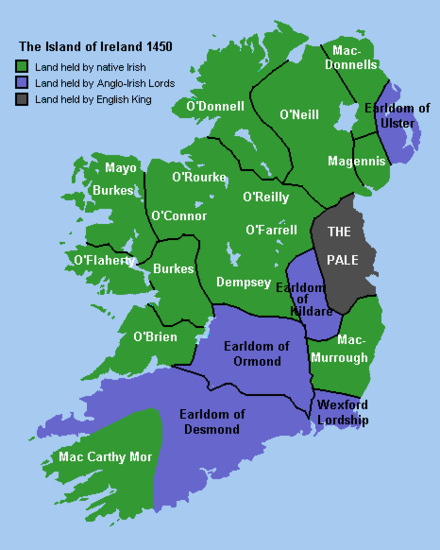

However in Ireland things were different, and Henry had a much harder time putting his plan into operation. For one thing, having been for a very long time the centre of Catholicism, even when the Roman Empire held sway over the Eternal City, Ireland had a lot more monasteries, convents and friaries than England did. About twice as many, in fact. Henry’s authority in Ireland was quite nominal; though he was officially declared King of Ireland, in reality his power only extended to the area around the Pale (as discussed in a previous entry) and so in order to work his will he had to make deals with local Irish lords. This meant that the land, and the wealth of the monasteries mostly went to these compliant lords as compensation, so the Crown saw little return for its efforts. In fact, up to the time of the accession of Elizabeth, Henry’s daughter, half of the monasteries in Ireland had not been dissolved.

) and therefore we are not seen as an oppressive nation, unlike Britain, Germany and the USA among others. We have only been an independent, free country for less than a century, which makes us a very young country in comparison to most of the rest of the world, and we have been on the receiving end of occupation, oppression, injustice and discrimination.

) and therefore we are not seen as an oppressive nation, unlike Britain, Germany and the USA among others. We have only been an independent, free country for less than a century, which makes us a very young country in comparison to most of the rest of the world, and we have been on the receiving end of occupation, oppression, injustice and discrimination.

Newgrange is therefore more or less accepted as one of the oldest monuments in the world today. It is probably well known (but I’ll tell you anyway in case you aren’t aware) that it is more than just a simple burial chamber. It is of the type known as a “passage tomb”, due to its long narrow approach to the burial chamber itself.

Newgrange is therefore more or less accepted as one of the oldest monuments in the world today. It is probably well known (but I’ll tell you anyway in case you aren’t aware) that it is more than just a simple burial chamber. It is of the type known as a “passage tomb”, due to its long narrow approach to the burial chamber itself.

But seriously, it’s a hard concept to get: how can you have one god who has a son and another part of him, each separate yet of the same being? Patrick explained this by picking a shamrock, and showing that though it has three leaves, they all rise from the one stalk. And so the people finally got it, and the shamrock became one of our most treasured plants, and indeed the emblem of our country.

But seriously, it’s a hard concept to get: how can you have one god who has a son and another part of him, each separate yet of the same being? Patrick explained this by picking a shamrock, and showing that though it has three leaves, they all rise from the one stalk. And so the people finally got it, and the shamrock became one of our most treasured plants, and indeed the emblem of our country.

are actually Scottish by ancestry…

are actually Scottish by ancestry…