Fail of the Century - The Great Famine (1315 - 1317)

It really must have sucked living in the first half of the fourteenth century in Europe. Not just because of the conditions, the poverty and the really poor wifi signal, but from halfway through the second decade up to more than halfway through the century famine and plague ravaged the land. As already related, the horror of the Black Death swept through Europe like, well, a plague from about 1347 to nearly 1352, wiping out over 200 million people, and this on the back of an already weakened Europe which had succumbed to a series of famines that raged from 1315 onwards. It’s amazing anyone survived.

Not that famines were new or unknown. France suffered from three separate ones before “the big one”, and a staggering six after it, some of them occurring during, and after, the time of the Black Death, while in England - yes, famine in England! - there were three. Life expectancy in Europe had dropped by 1345 to a mere seventeen years (though admittedly that was at the height of the Plague) from a relative high in 1276 of thirty-five. A spate of unseasonably cold and wet weather, coupled with poor harvests and climbing food prices, to say nothing of an explosion in population and the poor being confined to working on land that was hardly arable, all the best land kept for the nobility, pushed Europe along a steadily-descending spiral into almost constant and perpetual hunger. Nobody had enough to eat, and those who did did not care about those who had nothing. No social welfare, no land reclamation projects, no mechanical assistance to farming, and no mercy from the vagaries of fate.

It all led, in 1315, to what became known as The Great Famine (not to be confused with the infamous Irish Great Famine, which was confined mostly to Ireland and was five hundred years later), which was to last for two years and cover all of Europe. Heavy rain in the spring and summer of that year led to bad or in some cases no harvests, no fodder for livestock, and, market forces doing what market forces do, the scarcity of food pushed the price of any that was available beyond the reach of the ordinary worker. In fact, in France, the price of a simple loaf rose so steeply (increasing by, wait for it, three hundred and twenty percent!) that bread could not be purchased, in a stark future echo of events that would lead to revolution there four hundred and fifty years later. England didn’t fare any better, with reports from Bristol in 1315 speaking with horror of people being so hungry they ate their children, and new arrivals in the local gaol being fallen upon and devoured by the starving prisoners already there. Don’t believe me? Don’t blame you. But here.

(From the Bristol Annal: Bristol Archives)

there was: 'a great Famine of Dearth with such mortality that the living coud scarce suffice to Bury the dead, horse flesh and Dogs flesh was accounted good meat, and some eat their own Children. The Thieves that were in Prison did pluck and tear in pieces, such as were newly put into Prison and devoured them half alive.

See? Even Edward II found it hard to find bread, and you know there’s a problem when the royal bakery is empty! The year dragged wearily by, but its successor brought no relief, as the rain continued to fall, harvests continued to fail, and some families, unable to sustain their own children, turned them loose to fend for themselves. The horrid word was whispered throughout the continent, though who can say if cannibalism was actually practiced? Then again, who can say it wasn’t? If you’re hungry and desperate enough…

And on it persisted, with 1317 as wet as the two previous years, though finally in the summer the rain stopped, but by then most of the damage had been done. It would take another eight years before things would begin to stabilise, and another ten after that the rats would arrive. Ironically, in some ways the famine could be seen as a necessary tool that reduced the overpopulation of Europe and allowed the meagre food supply eventually to stretch further, having to feed fewer people. An anonymous poem penned in 1321 probably said it best:

When God saw that the world was so over proud,

He sent a dearth on earth, and made it full hard.

A bushel of wheat was at four shillings or more,

Of which men might have had a quarter before…

And then they turned pale who had laughed so loud,

And they became all docile who before were so proud.

A man’s heart might bleed for to hear the cry

Of poor men who called out, “Alas! For hunger I die …!”

Poem on the Evil Times of Edward II, Anon.

The Great Famine and, later, the Black Death, served to weaken the power of the Catholic Church for, although in the latter (and presumably the former too) the plagues were blamed on man’s sins and pride, the Church was unable to deliver its flock from the wrath of God, and so became something of a clay idol; people had before placed all their trust in the priests, the Pope and his ministers, expecting to be saved if they only repented. But in the face of famine and the Black Death the Church was as powerless as the lowest commoner, and Popes died as easily as paupers, and people began to see the Church was not, after all, the all-powerful, indefatigable entity it claimed to be.

The arrival of the Great Famine began to turn the tide against Edward, as his troops began to succumb to the disease and food ran out, and his own general impatience for battle would lead to his and his brother’s defeat and death in the Battle of Faughart. Sadly there is no real account of what should have been one of the most important battles of Bruce’s career and of the Scottish Wars of Independence, but it seems that Edward took on a much larger force than he could cope with - reckoned around 20,000 - without waiting for reinforcements to arrive from Scotland, and perhaps like the Grand Old Duke of York in the song, he marched them up to the top of the hill at Faughart but did not get a chance to march them down again, as he was slain with most of his men by the English. In possibly an ironic twist, the battle took place close to the town which had been the site of one of the greatest massacres by the Scots, Dundalk.

Despite the defeat of his armies and the death of his brother, Robert the Bruce did manage one victory - two if you include outliving not only Edward I but his son too - in having the Pope formally recognise the independence of Scotland (even if England did no such thing) in 1324 and affirming Robert as King of Scots. Edward II died in 1327 and was replaced by his son Edward III. Robert continued invading and harrying England, and in 1328 the two kings met for the battle which would decide the first War of Scottish Independence.

The Battle of Stanhope Park

The power behind the throne: waiting in the shadows

Edward II’s marriage was not good. His wife, Isabella, known as the She-Wolf of France, had had enough of the king and taken a lover, the exiled Roger Mortimer, who had risen against him. While on a diplomatic mission to her native France it is believed Isabella hooked up with Mortimer and the two began to plot the downfall of her husband. Returning to England with a small army, and threatening to disinherit his son Edward III, then only thirteen, Isabella and Mortimer forced Edward II to abdicate, later, according to some accounts, having him murdered, and then taking the crown for themselves, nominally naming the young prince as the new king.

In June 1327 a large Scottish force led by Thomas Earl of Moray, Black Douglas and the Earl of Mar raided across the border into England, and Mortimer along with the young prince raised a large army to meet them. Typical disagreements arose within the English ranks, especially with some mercenaries from the country of Hainault (modern France/Belgium border) which depleted the English ranks as they fought among each other. Having sorted out their differences, Mortimer moved to intercept the Scots.

Except, he didn’t.

The Scottish army would not be pinned down; like ravaging ghosts they plundered and burned and pillaged the countryside, their passage marked by towering plumes of smoke that rose into the summer sky, but they never engaged the English force and wherever Mortimer went, there the Scots were not. As a result of this somewhat retreading of William Wallace’s original guerilla war supplies began to run low in the English camp and the mood soured. Finally an English scout was captured by the Scots, and sent back with a message to Mortimer that they were ready to do battle. After all the uncrowned king of England had done to try to take his enemy by surprise and catch them at a disadvantage, it was now the Scots who were dictating the terms of the battle, and they met him as directed on the banks of the Wear river, near Stanhope Park.

Apparently all of what follows is true!

The Scots had occupied the high ground, and therefore had the advantage over their enemy. The English sent longbowmen up the river to try to ford it and attack Bruce’s men but they were scattered by cavalry. The English next asked the Scots if they didn’t agree that it really wasn’t cricket, you know, their having the advantage of the higher ground, and wouldn’t they be terrific chaps and just come on down onto the plains where everyone would be equal, and the armies could battle it out, man to man? Unsurprisingly, the Scots yelled back “Nae thanks son, we’re braw here lad!” And stayed where they were.

Unbelievable.

I can imagine the Tommie at the Somme shouting over to the Germans in their machine-gun nests: “Now look chaps, this really isn’t fair is it? Why not climb out of those trenches and we’ll duke it out here in No-Man’s Land to see who deserves to be the masters of Europe?” Or Osama being told he was being a really bad sport, hiding up there in the mountains where the Americans couldn’t catch him, and would he not just do the decent thing and come out and take what was coming to him like a man? Oh, the hilarity of these chivalrous English!

Anyway, unprepared to maintain the traditional stiff upper lip and charge into a hopeless cause in a blaze of very brief glory, the English remained where they were, the Scots remained where they were, and nobody attacked anyone for three days. Bor-ing! I thought they told me when I joined up that it would be non-stop fighting, burning, attacking, cheering, with maybe the odd spot of raping thrown in! Anyone want a game of cards? What do you mean, you didn’t bring cards? Now I’m really depressed! When are we going to see some action?

Well, kind of never, lad. The king did get something of a surprise - nearly died of terror really (well he was only a teenager, and barely that) when the Scots slipped down in the night and - wait for it! - cut the guy ropes of his tent, collapsing it, then sodded off back up the mountain! While the English then slept in full body armour, expecting an attack, the Scots buggered off back across the border, negotiating bogs the English had thought impassable, and when they woke up in the morning the English army was alone. D’oh! The discomfort of tossing and turning in armour all night, for nothing! I need to scratch so bad!

The strangest battle I ever read of, I must say. You can’t say not a shot was fired or that nobody died (consider the luckless archers of Edward III) but in general there was a three-day do-nothing, where the Scots grinned down at the English and the English glared up at the Scots, and then the Scots went home. And yet, this battle - or, to be fair, the combined effect of the Bruce rampaging throughout northern England - was the final nail in the coffin of Edward’s resistance to the idea of Scottish independence. All but bankrupted by the war and the constant invasions, hardly able to pay even the mercenaries mentioned above, and humiliated and smarting from his treatment, he, or rather, Mortimer and Isabella, had no option but to accept King Robert’s terms and the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton was ratified in 1328, making Scotland an independent and sovereign kingdom and Robert its rightful king. This drew to a close 32 years of fighting, invasion, counter-invasion and pillage which constituted the First Scottish War of Independence, and a year later King Robert died, leaving Scotland in the hands of his young son, David.

But Edward had never agreed with the terms of the treaty (he had been excluded from the negotiations and from the signing by Mortimer and Isabella) and by the time he had grown to his majority and properly established his royal power he had Mortimer arrested, imprisoned in the Tower of London and later executed without trial, being hanged at Tyburn.

Two years later, the Second War of Scottish Independence began. This would last another quarter of a century.

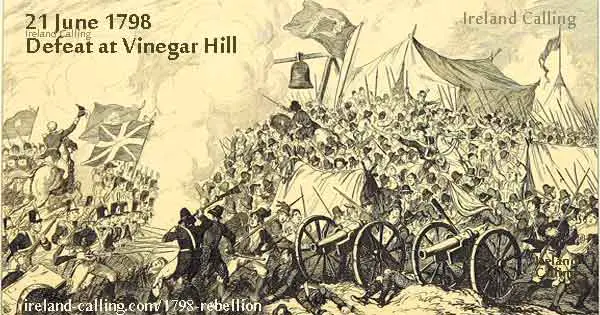

) they eventually bowed to pressure and allowed some of the prisoners to be shot, however that wasn’t enough and the barn was torched, those trying to flee shot, stabbed, beaten to death or forced back into the flames. All but two of the prisoners perished. The event horrified General Thomas Cloney, who reported “The wretches who burned Scullabogue Barn did not at least profane the sacred name of justice by alleging that they were offering her a propitiatory sacrifice. The highly criminal and atrocious immolation of the victims at Scullabogue was, by no means, premeditated by the guard left in charge of the prisoners; it was excited and promoted by the cowardly ruffians who ran away from the Ross battle, and conveyed the intelligence (which was too true) that several wounded men had been burned in a house in Ross by the military.”

) they eventually bowed to pressure and allowed some of the prisoners to be shot, however that wasn’t enough and the barn was torched, those trying to flee shot, stabbed, beaten to death or forced back into the flames. All but two of the prisoners perished. The event horrified General Thomas Cloney, who reported “The wretches who burned Scullabogue Barn did not at least profane the sacred name of justice by alleging that they were offering her a propitiatory sacrifice. The highly criminal and atrocious immolation of the victims at Scullabogue was, by no means, premeditated by the guard left in charge of the prisoners; it was excited and promoted by the cowardly ruffians who ran away from the Ross battle, and conveyed the intelligence (which was too true) that several wounded men had been burned in a house in Ross by the military.”