Winter is coming: the Year Without a Summer

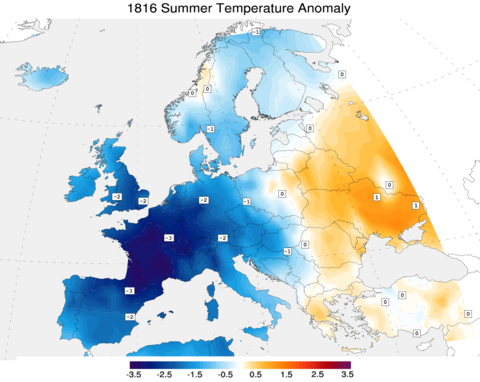

In 1816, one single year after the Corn Laws had been signed into operation, Mount Tambora in Indonesia erupted. The volcano threw huge clouds of ash and smoke into the air, cutting off sunlight and plunging the world into deep cold. In fact, over the last eight years there had been no less than five massive volcanic eruptions around the world, a comparable one to Mount Tambora being the eruption two years previous of Mount Mayon in the Philippines, causing the world to undergo a catastrophic change in climate. The image above shows how cold it got in that year, compared to normal average temperatures. The whole planet was affected as crops failed everywhere. China found itself in the grip of a massive famine, torrential floods and snow in Taiwan, while India was battered by rain which exacerbated an outbreak of cholera across the country.

The newly-struggling independent colonies did not fare much better. Though there was no famine, and they were used to colder temperatures as the norm, seasons seemed reversed in areas of America such as Massachusetts, New York and Vermont, and crops again failed. William G. Atkins, in The History of Hawley, West Massachusetts wrote “Severe frosts occurred every month; June 7th and 8th snow fell, and it was so cold that crops were cut down, even freezing the roots … In the early Autumn when corn was in the milk it was so thoroughly frozen that it never ripened and was scarcely worth harvesting. Breadstuffs were scarce and prices high and the poorer class of people were often in straits for want of food. It must be remembered that the granaries of the great west had not then been opened to us by railroad communication, and people were obliged to rely upon their own resources or upon others in their immediate locality.”

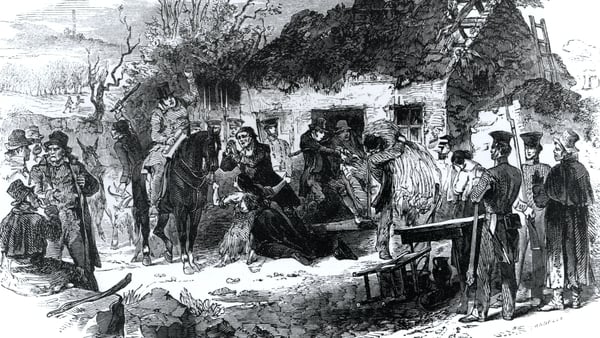

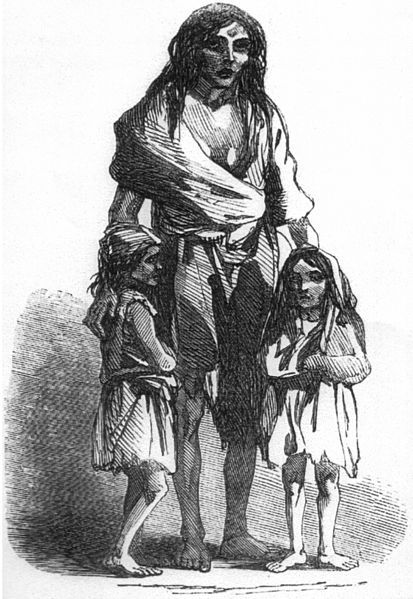

And in Europe, as rain pelted down and freezing frost killed the crops, starvation and disease spread all over the continent. Typhus claimed hundreds of thousands of lives, people roamed the streets begging for food, other people took the law into their own hands and rioted, demanding “bread or blood”, while strange phenomena were recorded in Hungary, where brown snow (a result of the volcanic ash in the air) fell, and Italy, where it seemed to rain blood, though again this was snow tinged red by the eruption’s ejecta. As in the time of the Black Death, people must have thought the end of days had come. For some, of course, this would prove to be true, and as always, the awful weather and failure of crops would disproportionately affect the poor.

I suppose at this point you couldn’t really blame the British for not having lowered the ceiling to import corn - where were they going to import it from, after all? - but the real damage the Corn Laws would wreak would of course be seen in its legacy with regard to the Great Famine. There were some amendments made to the laws, but they were impractical, restricting the price of corn to be imported to the extent that it never had any chance of reaching that level, and things stayed as they were. Many British politicians and industrialists, though, had had enough.

The Anti-Corn Laws League

In 1838 a confederation of these men got together and formed the Anti-Corn Laws League (well, it had been formed two years earlier, but only gained nationwide appeal in this year) in an attempt to force the repeal of the unpopular laws, which, they said, strangled Britain’s trade and were unfair and biased. It’s probably likely that not one of these people considered the Irish in their speeches and the pamphlets they wrote, or mentioned them at the many meetings held; these men were all about protecting British interests, though eventually repeal of the Corn Laws would have a positive effect on Ireland.

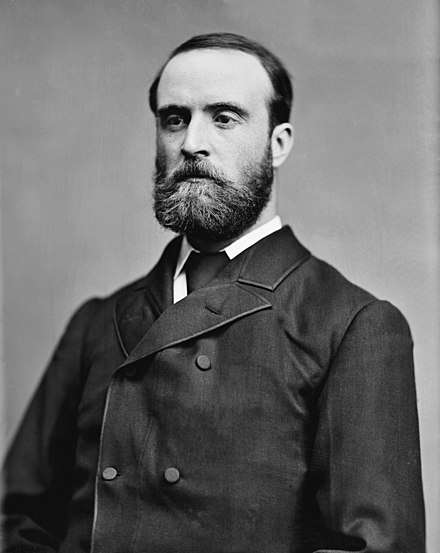

Richard Cobden (1804 - 1865)

(All right, is there not something ironically funny about a guy whose name contains the word “cob” opposing the Corn Laws? No, you’re right: this is no place for jokes. Over there, that’s the place…)

One of the leaders of the League, Cobden was a Liberal, a Radical and would later be instrumental in securing free trade with France, in the 1860 Cobden-Chevalier Treaty. The son of a poor farmer, his sympathies of course then came to lie with the tenant farmers, but he was determined to better himself and not live as his father had done. A man to whom nothing was handed on a plate, he worked in his uncle’s business until that failed, while at the same time trying to improve on the meagre education his family had been able to afford for him, and eventually set up his own printing business, and soon got into politics, standing for the seat of Stockport in 1837, though he did not win it till four years later. He quickly established himself as an expert and authority on the Corn Laws, and in 1843 took Prime Minister Robert Peel so to task on the subject that he was accused of inciting to violence.

Peel. however, was changing his stance and, swayed partially at least by Cobden’s passionate rhetoric, became a supporter of repeal and in 1846 accomplished this, finally removing the hated laws. Though he had wished to rest after his exertions, which had taken considerable reserves not only of his time and money but also his health, and travelled extensively in Europe, he soon found that his fame had preceded him, and he was something of a celebrity. Bowing to the inevitable, he declared “Well, I will, with God’s assistance during the next twelve months, visit all the large states of Europe, see their potentates or statesmen, and endeavour to enforce those truths which have been irresistible at home. Why should I rust in inactivity? If the public spirit of my countrymen affords me the means of travelling as their missionary, I will be the first ambassador from the people of this country to the nations of the continent. I am impelled to this by an instinctive emotion such as has never deceived me. I feel that I could succeed in making out a stronger case for the prohibitive nations of Europe to compel them to adopt a freer system than I had here to overturn our protection policy.”

A great ambassador for peace, Cobden argued that as “in the slave trade we [the British] had surpassed in guilt the world, so in foreign wars we have the most aggressive, quarelsome, warlike and bloody nation under the sun.” He also thundered “you will find that we have been incomparably the most sanguinary nation on earth… in China, in Burma, in India, New Zealand, the Cape, Syria, Spain, Portugal, Greece, etc, there is hardly a country, however remote, in which we have not been waging war or dictating our terms at the point of a bayonet.” Cobden believed the British, “the greatest blood-shedders of all”

This could not have made him popular back home. Nobody likes to be reminded of their mistakes, or what might be seen as the excesses of youth, in terms of empire, and the late Queen Victoria would most certainly not have been amused. He was proven correct however in his assessment of the seemingly insatiable British thirst for war, conquest and the need to “show other nations who was boss” when they declared war on Burma (now Myanmar) for the specious reason that they took exception to how the government there had treated two of their captains. Cobden wrote in disbelief:

“I blush for my country, and the very blood in my veins tingled with indignation at the wanton disregard of all justice and decency without our proceedings towards that country exhibited. The violence and wrongs perpetrated by Pizarro or Cortez were scarcely veiled in a more transparent pretence of right than our own.” The Burmese, Cobden continued, had “no more chance against our 64 pound red-hot shot and other infernal improvement in the art of war than they would in running a race on their roads against our railways… the day on which we commenced the war with a bombardment of shot, shell and rockets…that the natives must have thought it an onslaught of devils, was Easter Sunday!”

John Bright (1811 - 1889)

The other leading light in the Anti-Corn Law League was a Lancashire man, the son of a miller and a Quaker by religion, and acknowledged as one of the great orators of his generation. He learned this through giving speeches for the local temperance association, and later, after meeting Richard Cobden, formed the League with him. When his wife died in 1841 it gave him a greater incentive to have the Corn Laws repealed, so that no other person need die of hunger or neglect or poverty, and feel the pain he did at the passing of his wife from tuberculosis. In 1843 Bright was elected to the seat at Durham, and so sat in the House of Commons with his friend, who had been there two years before him.

Bright was responsible for two famous phrases, the first being “flogging a dead horse”, which he used as a way to illustrate how unwilling parliament was to pass the Reform Act of 1867, the other when he called England “The Mother of Parliaments”. He went on to become MP for Birmingham, a position he held for thirty years. Originally a supporter of the Irish Tenant Right League and Irish land reform, Bright changed his stance when the sectarian divide began to grow, and refused to support Home Rule for Ireland, calling the Irish “disloyal”. An odd phrase, I think, to use, considering we were never really willing subjects of the Crown, but there you go. This what what he had to say about an hour-long meeting he had with then-Prime Minister William Gladstone:

“He gave me a long memorandum, historical in character, on the past Irish story, which seemed to be somewhat one-sided, leaving out of view the important minority and the views and feelings of the Protestant and loyal portion of the people. He explained much of his policy as to a Dublin Parliament, and as to Land purchase. I objected to the Land policy as unnecessary—the Act of 1881 had done all that was reasonable for the tenants—why adopt the policy of the rebel party, and get rid of landholders, and thus evict the English garrison as the rebels call them? I denied the value of the security for repayment. Mr G. argued that his finance arrangements would be better than present system of purchase, and that we were bound in honour to succour the landlords, which I contested. Why not go to the help of other interests in Belfast and Dublin? As to Dublin Parliament, I argued that he was making a surrender all along the line—a Dublin Parliament would work with constant friction, and would press against any barrier he might create to keep up the unity of the three Kingdoms. What of a volunteer force, and what of import duties and protection as against British goods? … I thought he placed far too much confidence in the leaders of the rebel party. I could place none in them, and the general feeling was and is that any terms made with them would not be kept, and that through them I could not hope for reconciliation with discontented and disloyal Ireland.”

He was less than impressed when Gladstone signed the Home Rule Bill into law only two weeks later. Returning from the funeral of his brother-in-law, and in response to a request to visit the PM, he wrote: “I cannot consent to a measure which is so offensive to the whole Protestant population of Ireland, and to the whole sentiment of the province of Ulster so far as its loyal and Protestant people are concerned. I cannot agree to exclude them from the protection of the Imperial Parliament. I would do much to clear the rebel party from Westminster, and do not sympathise with those who wish to retain them—but admit there is much force in the arguments on this point which are opposed to my views upon it. … As to the Land Bill, if it comes to a second reading, I fear I must vote against it. It may be that my hostility to the rebel party, looking at their conduct since your Government was formed six years ago, disables me from taking an impartial view of this great question. If I could believe them honorable and truthful men, I could yield much—but I suspect that your policy of surrender to them will only place more power in their hands to war with greater effect against the unity of the 3 Kingdoms with no increase of good to the Irish people. … Parliament is not ready for it, and the intelligence of the country is not ready for it. If it be possible, I should wish that no Division should be taken upon the Bill.”

It’s therefore clear to see that, though these two men fought for the working poor, it was the English working poor they championed, and that neither had the slightest interest in the plight of the Irish tenant farmer. In fact, as we can see above, Bright positively loathed the Irish south of the border. But what about the man at the top? No, not the king: any real power the monarchy had held disappeared with about six inches of King Charles I. England - Britain - was and is a constitutional monarchy, and the head of state is more a figurehead than anything else. He or she possesses no influence over the government, and exists mainly as a sort of rubber-stamp for parliament’s policies. What the king thought of the Irish situation - if indeed he thought of it at all - I don’t know, and it doesn’t matter. English kings had been sympathetic - either covertly or brazenly - to the Irish cause (or at least the Catholic cause, which was not always by any means the same thing, but the two did sometimes dovetail) and it had been the ruin of them. Remember James II? No, I’m talking about the real power, the man who led the country, the man who had the mandate to get things done.

This guy.

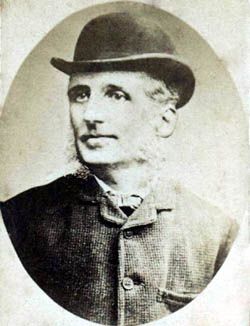

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd baronet (1788 - 1850)

Although his tenure as Prime Minister (the second time he held the post) would in fact end one year before the Great Famine began - and although he himself would die during the famine years, though obviously not of hunger) Peel was the man in whose hands the fate of Ireland lay, as he was the only one capable of repealing the hated Corn Laws. As we’ve read above, this would in fact happen far too late to save the millions that died or were forced to emigrate in the Great Famine, but throughout his term as Prime Minister he wrestled with the question, trying to keep his own people onside, and eventually more or less fudged the issue. More about that in due course, but for now, what about the man behind the title? Well, everyone will surely know he was responsible for setting up London’s first proper police force, the Metropolitan Police, the precursor of today’s modern police force, and which were known colloquially at the time as “Peelers”, for obvious reasons. Also “bobbies”, again due to his name.

Like John Bright, Peel was born in Lancashire, but there the similarities end. Peel came from a rich family, one of the richest in the country. His father was a textile magnate, and Robert was sent to Harrow Public School (always amazes me how the English system of exclusive, expensive education is called public rather than private - I think the “common” schools were - and may still be - called grammar schools?) where he hung out with the poet and writer Lord Byron. At the age of 21 he entered politics, sponsored for a “rotten borough” (read, controlled by the landowner, so who they wanted to get the seat got the seat) in Cashel, Co. Tipperary by the Duke of Wellington, who would become a great friend and ally of his.

Though he served as Chief Secretary of Ireland (a post previously held by the Duke) and laid the basis for the Royal Ulster Constabulary by bringing in some of his “peelers”, he was no friend to Ireland, opposing Catholic emancipation and defeating Henry Grattan’s bill in parliament. For a time, his anti-Catholic stance told against him, as, given the post of Home Secretary in 1822, he had to resign when the PM did, his successor an advocate of Catholic emancipation. He didn’t last long in the post though, and when the Duke of Wellington became Prime Minister, Peel was made Home Secretary again in 1827, believed to be the Duke’s right-hand man and second, as it were, in line to the throne.

As we’ve already seen, Peel’s change of heart on the issue of Catholic emancipation was not due to any softening in his position, but to the unexpected and quite unwelcome election of Daniel O’Connell to the Clare seat, and the potential for civil war in Ireland should he not, as per the Penal Laws then in force, be allowed to take his seat. As a matter of pragmatism, then, and in order to avoid civil unrest or even outright war in Ireland, he pushed through the Roman Catholic Relief Bill, helped in the House of Lords by his mate the Duke of Wellington, who threatened to resign if the king did not sign it into law, despite furious opposition by his own party. Thus were the Penal Laws removed and Catholics a step closer to equality with their Protestant neighbours.

Peel of course also set up the Metropolitan Police Force, as I mentioned in his introduction. Originally a force of 1,000 constables, they were based out of Scotland Yard, and took over from the unpaid parish constables who had, until then, overseen law and order (and, it has to be said, with varying degrees of success and indeed interest - after all, if you’re not being paid for your work, why throw yourself into the line of fire?) and supplementing the Bow Street Runners, the city’s first detective force, created in 1753. The deployment of the Metropolitan Police (later, and even now, known as the Met) saw greater prosecution of crime, a more zealous sense of service to the community, and a more organised approach to fighting lawlessness in the streets.

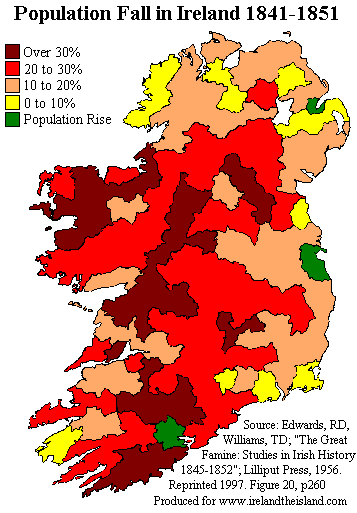

His first term as Prime Minister in 1834/5 ended badly, all his policies frustrated by the opposition Whigs in collusion with Daniel O’Connell and his Radical Irish Party, and after 100 days Peel resigned. He returned to power in 1841, giving him the opportunity, which he took - and which brought down his government - to repeal the Corn Laws. Having previously noted that the scale of the problem was likely much less severe than reported: "There is such a tendency to exaggeration and inaccuracy in Irish reports that delay in acting on them is always desirable” - he perhaps in hindsight worried that history might judge him as partially, or even fully responsible for the Great Famine (which he kind of was, as the Prime Minister who did nothing to help the starving Irish, though he was by no means alone) and so got the repeal through, with the help of his friend and ally in the House of Lords. It came, of course, too little too late, but he was probably more concerned with his place in the history books than how he could actually save lives.

His Irish Coercion Bill - a request for greater powers to suppress revolutionary elements (and this was taken mostly to mean in Ireland) - presented to the House on the same night, shows he was no friend to the Irish. The bill, however, was defeated and he resigned a few days later.