Big Rice fan of course, also Brian Lumley (two very different vampire authors) but I’ve never heard of Hellsing. You’ll have to link me, but I expect it’s more recent, and I’m starting from the eighteenth century so, you know, might take some time…

Meet the Ancestors (sort of)…

So to return to the question I asked at the beginning, and never answered, who or what was the first vampire? I didn’t answer because it’s pretty hard to say. Where does the line between blood-drinking demons or evil spirits and actual vampires lie? Are they both the same? Is one the progenitor of the other? We can look to the Bible, or further, as much of what is in that Holy Book is based on earlier legend anyway, and there we find one of the candidates for the first vampire, who is, rather ironically, a woman.

Lilith, or Lilitu

Perhaps marking one of the first, but enduring, beliefs that women cause all the trouble (thank you, Book of Genesis!) Lilith crops up in Hebrew belief as the first wife of Adam, but is originally based on figures from ancient Assyrian and Babylonian myth, where she is known as Lilitu, which means night hag, night demon, night monster etc. Unlike the Christian Eve, who is said to have been created from one of Adam’s ribs, Lilith is depicted as having been made from the same clay as him, so technically while Eve would be seen, from the moment of her creation, as a part of and therefore inferior to Adam, Lilith can be seen to be all but equal to him. Nevertheless, according to Hebrew scripture, having refused to be subservient to Adam she ran off and got it on with an angel, said to be Sammael, the Jewish figure of Satan himself, afterwards refusing to return to the Garden of Eden.

Although it’s hard to confirm, with such ancient religions leaving behind few written accounts and ideas and opinions changing as time continues its inexorable march, Lilith in Sumerian belief seems to have been a demon who flew around the underworld bringing nightmares, and is seen as a hateful figure who can, something like a succubus, transform herself into the likeness of a man’s wife and conceive a child with him. Later, Lilith would seek revenge upon the true children of the man and woman, making her a thing to be feared by children and parents alike. This legend would survive into Hebrew times, where the words “lilith-abi” would be inscribed on four amulets hung in a child’s bedroom by Jewish mothers, meaning “Lilith - begone!” and give us our present-day word lullaby.

From the stories told about her, it’s probably fair to demote, or promote, Lilith to the level of a witch - perhaps the first witch - rather than a vampire, but she is said to have drank the blood of infants and to have stirred the desire of men, whereas the vampire, particularly the romantic variation, certainly directed his sexual power at women, or occasionally, if female, at men. There are instances of homosexual or at least bisexual vampires in the writings of Rice and Lee, but they don’t seem to be based on any legend and are surely just there for the advancement of their stories and the development of their characters.

Lamia

Essentially another incarnation of Lilith, Lamia was changed into a bestial being by the Greek goddess Hera after all her children had been destroyed by Zeus’s wife (or she had compelled Lamia to do so herself) in retaliation for Lamia sleeping with her husband. Alternatively, she was a Libyan queen who ordered infants snatched, Herod-like, from their mothers and killed, her savagery affecting her appearance and turning her into a monster. More horribly, the Greek philosopher Aristotle spoke of a ravening beast which tore open the bellies of pregnant mothers and devoured the fetuses. Lamia is the first of these beings to be given shape-shifting abilities, something that would become attached to the vampire myth.

Because of the above, the Lamia became a name used to frighten children into good behaviour, a kind of ancient bogeyman, and she began to be depicted as half-woman, half-serpent. This possibly removes her from the running for being a true vampire, but there are references to her and her kind sucking and drinking blood as well as seducing sleeping men, so some aspects are definitely there. Intelligence and gentility, however, attributes given to the modern vampire, are not: Lamia and her fellow creatures are said to be stupid, and to stink.

A similar creature, called the empousa, was known to target young men for the quality and purity of their blood, and would fatten up her victims before killing and devouring them. This is not necessarily something that translated to the later vampire myths, though Dracula is seen encouraging Jonathan Harker to eat at his castle, while he, the Count, partakes of no food, and it is later revealed that there are three hungry female acolyte vampires in the cellars or dungeon of the castle who wish to feed on him. Other features of the empousa, such as having a foot made of bronze or cow dung, and being frightened away by loud noises, certainly do not conform to our stereotype of the vampire.

Strix

Perhaps leading to the involvement of the vampire bat in the legend, the strix was a bird of antiquity said to feed on the blood and flesh of humans. Description of it as a “nocturnally crying creature which positioned its feet upwards and head below” lends more weight to this possibility. The strix is the first case where we hear of the efficacy of garlic against the beast, which might help explain why it’s seen as being useful in warding off vampires. Strix were also said to be the transformed Polyphontes, in retribution by the gods of she and her sons’ cannibalistic tendencies (this also explaining why these strange birds craved human flesh and blood). Striges (plural of strix) have been called “vampire owls”, which certainly fits the description of their behaviour. Later, it was believed that striges transformed into witches, and vice versa, lending more credence to the myth of their association with vampires and creatures of darkness.

Vetala

Really more a precursor to the Haiitian zombie, the vetala comes from Indian legend, where it would inhabit the corpse of a recently-buried person and reanimate it, though it does not seem to have been to any evil end, more for mischief. Additionally, vetala are not said to have drank blood, though they did hang upside-down like bats.

Shtriga and dhampir

Dhampir sounds very close, doesn’t it? But let’s deal with shtriga first. Basically witches in Albanian folklore, they were said to possess the evil eye and could curse people, being the only ones who could lift the curse. It was feared they sucked the blood of infants at night, and transformed into flying insects once they had had their fill. One explanation offered for their being evil is that they were childless women, who were jealous of the offspring of others. Again, garlic was used to ward against them or banish them. The crucifix and holy water comes in here too, perhaps for the first time, though as usual it’s the Catholic Church trying to assert its power over the pagan monsters.

Despite what I said about the name though, dhampirs can’t be considered as forebears of the vampire, as they appear to be the result of a union between a vampire and a human. In fact, Slavic tradition has it that dhampirs could see vampires who were invisible to other eyes, and this led to many of them pursuing a career as vampire hunters. Dhampirs were supposed to have no shadow - a handy attribute if you are a vampire hunter - and no bones (not quite so handy), making them seem “slippery and jelly-like”. Uh-huh. Some of the more famous fictional dhampirs are Blade, Connor from the series Angel and Rayne from the movie Bloodrayne.

Moroi and Strigoi

One of almost the birthplaces of the vampire, at least the romantic, novellised one, is Romania, and Stoker set his seminal novel near here, in the Carpathian Mountains. Not too surprising, when you hear the tales and beliefs that emanated from that area. Moroi were basically ghosts which left the grave to trouble the living, while strigoi were witches with two hearts and two souls, which could send out their spirits at night to meet up with others of their kind and attack and consume the blood of animals and humans. After death, strigoi would roam the night, attacking their living family, drinking their blood. Interestingly, in Romanian folklore there were several ways people could become vampires, and some were born fated to be nightcrawlers. A living strigoi would, when she passed away, become a revenant, a dead (or undead) strigoi, but any unbaptised child, anyone who was born with a caul, an extra nipple, a tail or extra hair was also doomed to become a vampire.

If you happened to be the seventh boy or seventh girl in a family of all the same sex, that was it for you: vampire in the making. Similarly, if your mother had the bad luck to have a black cat cross her path, if you were born too early, out of wedlock or had blue eyes and red hair your fate was sealed. A pregnant woman who didn’t eat salt, or one considered a strigoi was liable to give birth to a vampire, and anyone who died an unnatural death was also at risk.

__________________|

Born to Darkness: Recipe for a Vampire

Following on from the above, the Slavic countries seem to have held very firm ideas about how one became a vampire, so let’s have a look at some of them here.

Dabbling in the black arts, being a conjurer or magician

Being a person of poor moral fibre

Unnatural death

Untimely death

Suicide

Born with a caul

Born with a tail

Improperly buried

Animal jumping or bird flying over the corpse or the empty grave

Incest between mother and son

Living a life that was not pious

Dying alone or unseen

Corpse swelling or turning black before burial

Some Slavic regions believed the genesis or birth of the vampire was a gradual event which went in stages. In the first forty days the vampire was most vulnerable, as it started out as an invisible shadow (?) and then as it fed gradually got stronger, forming an invisible (again) boneless, jelly-like mass before finally taking on a full human body. It was then free to roam, even visiting its widow or other women and having children by them. These children had the special sight that resulted in their being the dhampirs as noted above, preparing them for a life as vampire hunters. Not quite following in father’s footsteps, then!

So much for “real” vampires, so far at least. We’ve explored how vampires are supposed to be created, how they can be killed or thwarted, we’ve looked into some of the beliefs surrounding them (and will again later, going a little deeper) and we’ve theorised about who or what the very first vampires were, where they came from. We’ve outlined the characteristics, powers and the various Achilles heels of vampires, and seen the role religion, especially Christianity plays or played in keeping them at bay or destroying them.

But where vampires really started to come to life, so to speak, was in the pages of eighteenth and nineteenth century literature. Gothic fantasies, horror stories, even romances as humans began to have encounters with these evil but fascinating beings. In fact, were it not for the various stories and novels written about them, it’s likely the vampire would be forgotten now as an ancient remnant of an ignorant belief, the name Dracula would mean nothing to us, and Hollywood would have had to look elsewhere for its big moneyspinners.

So let’s look next at vampire literature, and media later, but written material first. And if I can, I want to try to do this chronologically. Which means we begin with this.

Timeline: 18th century

Note: It seems that somehow I missed out some of the earlier, indeed, earliest references to vampires when I started this, so let me amend that now. Oddly enough, my many books of vampire lore tend to be quite mute on the early material, only mentioning the more well-known ones, so I have to trust Wiki and then search out examples, or extracts, or if I’m lucky, whole texts, if they’re available.

In the light of this, we now have starting off our history of vampire literature the very first ever mention of the breed in fiction, this honour going to another, different German poet from the eighteenth century.

Title: Der Vampir

Format: Poem

Author: Heinrich August Ossenfelder

Nationality: German

Written:* 1748

Published: 1748

Impact:** ? but given it’s in German probably not much

* Unless I have information to the contrary, I’m going to suppose the piece was published in the same year as it was written. This may not always be the case, but the composition date is seldom shown, just the publication one.

** Refers to not only the impact on vampire and gothic literature, but also on the wider world. Scored from 1 to 10. This will begin to fade out as vampire literature (and later, movies) becomes more widespread, but it’s important with the early works to show how they affected society and literature in general. In the case of works not in English, it’s likely I won’t be able to gauge its effect on its readership, unless it’s mentioned.

Synposis: None really. It’s written as a kind of threat, warning or even dark promise to a woman called Christine (not sure what the attraction of this name is, Coleridge uses a similar one for his poem: maybe the similarity to Christ?) that she will fall victim to a vampire. It does mention the drinking of blood, so therefore the first time this is broached in literature, though Ossenfelder refers to vampires as unmortal, rather than immortal or undead. He also seems to begin the trope - surely taken from the folk beliefs - of a vampire coming in upon a sleeping victim and draining their blood, I assume this always being due to people being most off their guard while asleep, as the Major in Fawlty Towers once remarked. The power of the vampire to hold sway over its victims is described in the final lines of the poem:

“And last shall I thee question

Compared to such instruction

What are a mother’s charms?”

Intriguing to see he uses the couplet “sleeping/creeping”, which would become part of Poe’s famous The Raven almost a hundred years later. Yes, they’re common words, but I find it noteworthy that they’re used here in another gothic, nightmarish poem which also references death and has an implacable enemy as its protagonist, who seems destined to triumph at the close of the poem.

But back to this one. It would appear the vampire is exulting in his power over Christine, and basically telling her nobody can protect her, least of all her mother, who is powerless against his magic. The poem doesn’t always rhyme, but then I’m reading the translation from German, and it surely loses something in the conversion to English. Not all poetry, of course, has to rhyme, but some of the lines here seem out of place, though again I imagine that’s due to their being translated and the German version probably flows much better.

It’s unclear here whether the narrator is actually a vampire, or is just comparing himself to one to frighten and terrorise the girl, who has apparently jilted him. Hard to be sure: he talks of “draining your life blood away”, but whether that’s just a fancy way of saying he’s going to murder her or whether he actually intends to drink her blood, is left fairly ambiguous. Then he speaks of “crossing death’s threshold” with her “in my cold arms”. So is he going to kill himself too (otherwise why the description of his arms as cold?) or is he really a vampire?

The poem is very short - only twenty-two lines - but it raises a whole host of questions. Who is this guy? Was she betrothed to him? Was he an unwelcome suitor, what we would call today a stalker? Was she/is she afraid of him? What did she do to incur his wrath, or did she in fact do anything, and is this all in his twisted imagination? Perhaps it’s because she won’t even look at him that he considers murderous revenge. Maybe it’s something to do with the mother: did she advise her daughter against starting a relationship with him, or convince her to break off the one she had, if she had one? Is he intending to punish the mother by taking her daughter? Is it even (pause for gasp of horror) possible this is her father, intent on raping and killing her?

Although it’s not by any means made clear that he is a vampire - maybe he thinks or wishes he was one, maybe he just wants to frighten her by using the local legends, or maybe he’s just likening what he’s going to do to her to what a vampire would do (“to a vampire’s health a-drinking”) - it’s still the first mention of the term in literature, the word only mentioned twice in the poem, with blood drinking once and death once. Few texts would specify a vampire, their authors preferring to let the reader make up his or her own mind, but the seed had been planted and the very idea of vampires had begun its slow and indomitable stalk through the pages of literature, a presence that would only increase and become more prevalent down the next hundred years or so.

Title: Lenore

Format: Poem

Author: Gottfried August Bürger (mmm… burger!)

Nationality: German

Written: 1773

Published: 1774

Impact: 10

Although neither the first real reference to vampiric beings in literature, nor strictly speaking a vampire piece, Lenore is accepted as one of the first poems to actively portray someone ostensibly coming back from the dead, and was a huge influence on the later genre of vampire and gothic fiction. A product of its time, it also cautions against pissing God off, as we’ll see.

Synopsis: A woman, upset at the failure of her husband to return from the wars in Prussia, rails against God for taking him. Her mother tells Lenore to repent, or God will punish her and she will go to Hell, but she will not. She says God has never done her any good. Some time later she is visited by a stranger who takes her on horseback by night to where he says is their marriage bed. Lenore, thinking that this is her husband returned, is happy until, at sunrise, they arrive at the cemetery gates and it’s clear that the figure is in fact Death. He takes her to her husband’s grave and she realises she is dead, Death telling her she should not have spoken out against God.

Again, although this is not considered a vampire story, the nascent elements of what would become vampire and gothic fiction are here. A figure, not standing by the foot of the bed or over the sleeping girl, as would become the motif for vampire fiction, but nevertheless arriving mysteriously at night, offering her a choice: come with him and discover what he has to show her or remain where she is, and remain ignorant of the fate of her husband. A fascination with death and the unknown, a veiled threat of death, gothic images such as dancing skeletons, moonlight, black horses and graveyards, all to become features of vampire books, stories and later films.

Bürger uses a phrase here that will crop up again and again in not only vampire or gothic literature, but in other genres too, even used by Dickens a hundred years later, when Lenore asks Death, riding before her on the horse, why they are galloping so swiftly, and he replies “the dead travel fast.” The phrase is also used in the opening chapter of what must surely be the seminal vampire novel, Bram Stoker’s Dracula

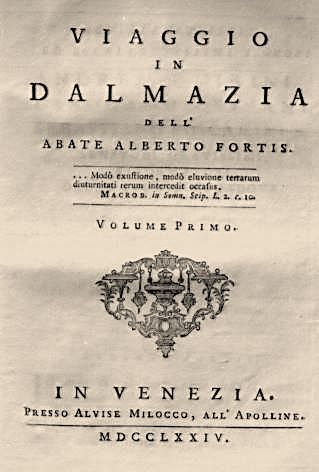

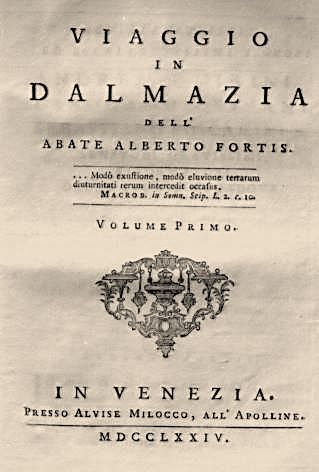

Title: Travels into Dalmatia; containing general observations on the natural history of that country and the neighboring islands; the natural productions, arts, manners and customs of the inhabitants: in a series of letters from Abbe Alberto Fortis

Format: Travelogue

Author: Alberto Fortis

Nationality: Italian

Written: 1774

Published: 1774

Impact: ?

Synopsis: After exhaustive research I’ve been unable to track down a copy (unless I’m a member of various libraries, which I ain’t) or even an extract from this. All I can tell you is what Wiki tells me, that it features a fight against vampires, which really makes me wish I could get it, but I can’t, so we move on. Must be noted as the first Italian vampire story anyway.

Title: The Bride of Corinth ( Die Braut von Korinth)

Format: Poem

Author: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Nationality: German

Written: 1797

Published: 1797

Impact: ?

Synopsis: A youth comes to Corinth seeking his bride, but tired he beholds instead a beautiful young woman who “in-hies through the door with silent tread” (which I think is meant to mean she sort of floats in?) and he of course falls in love with her. But she is distressed, and tells him she is the sister of the girl he is to marry, and she herself has been locked away, with the intimation that she is dead. Nevertheless, stricken by her beauty the youth pledges himself to her, and they exchange tokens, she giving him a golden chain and asking for a lock of his hair. Midnight strikes, and she seems happy at the sound; she drinks the wine (“blood-red”) but won’t touch the food no matter how much he tries to persuade her.

He sinks into despair and she comforts him, but again seems to intimate that she is dead, or dying (Yes! the maid, whom thou/Call’st thy loved one now,/Is as cold as ice, though white as snow”) and he embraces her, sharing his breath with her (as if he believes she is dead). Just then the mother appears, and shocked at seeing her dead child there she realises - if she hadn’t already - that she is a vampire. Sort of. I mean, it’s not actually said, and the word is never used once here, the only draining going on being breath to breath and not even a mention of blood, other than the wine, but she does tell the young fellah that he’s doomed now that he’s shared her kiss, and will die tomorrow. Well, that’s just wonderful, isn’t it? Come here all the way to meet my bride, take pity on (read, get horny for) her sister and then I have to die. What a world!

Goethe does a pretty good job here taking on the Church (presumably Catholic but it seems to refer to all Christianity, and given that the poem is based on an ancient Greek myth, it’s probably the new religion of Jesus they’re getting at). He has the (never named; in fact, nobody is named at all) girl complain that

“From the house, so silent now, are driven

All the gods who reign’d supreme of yore;

One Invisible now rules in heaven,

On the cross a Saviour they adore.

Victims slay they here,

Neither lamb nor steer,

But the altars reek with human gore.”

Later, facing her mother, she either laments or gloats at the efforts of the priests to help her, as she wanders from her coffin.

“But from out my coffin’s prison-bounds

By a wond’rous fate I’m forced to rove,

While the blessings and the chaunting sounds

That your priests delight in, useless prove.”

I suppose it’s the classic tale of doomed love, and though it’s not confirmed, the possession of the lock of his hair gives the girl power over the youth I guess, and damns him to her fate. Given that this is based on an ancient Greek legend which predates Christ, technically it could be said to be the very first vampire story, and certainly the first with a female vampire. Though is she a vampire, or just some unquiet spirit who can’t find rest? It’s not made clear, and in the ancient world were such things as vampires even known about or believed in? More likely she would have been seen as a revenant, or some evil spirit, even if she wasn’t necessarily what we would term evil.

Title: Christabel

Format: Poem

Author: Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Nationality: English

Written: 1797/1800

Published: 1816

Impact: 7

Note: Although only published in 1816, and therefore really a nineteenth-century piece, I’ve left this here in the eighteenth as it was written then. Plus, I forgot.

Said to have been a possible influence on what is generally regarded as one of the first proper vampires novels, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla as well as Edgar Allen Poe’s poem The Sleeper. Also, as an aside, possibly (though I have no idea) the first inference of lesbianism in Gothic - or indeed, any - fiction. Maybe.

Synopsis: Having gone into the woods to pray, Christabel finds a woman hiding behind a tree, who says she has been abducted and left there. Christabel offers to pray with her, but the woman, whose name is given as Geraldine, refuses, but agrees to accompany her rescuer back to her house, where they spend the night together. Though not actually confirmed as a vampire, she is barked at a by a dog, finds it impossible to cross an iron gate and has, when she disrobes, undefined but obviously worrying marks on her back which seem to mark her as a child of the devil. The poem, though written in two parts, was never finished, so unfortunately we never learn if Coleridge had intended for her to be taken as a vampire.

Timeline: 19th Century

Title: Thalaba the Destroyer

Format: Poem

Author: Robert Southey

Nationality: English

Written: 1800

Published: 1801

Impact: 3

Noted here only because it’s said to be the first time an English author/poet references vampires, “Thalaba the Destroyer” is a long, epic, Arabian Nights-style saga set in the Middle East, and the only point at which a vampire is mentioned is during one of the hero’s adventures, as detailed below. Other than that, I can’t see that it’s of any interest to us.

Synopsis: I have no intention of summarising the entire, twelve-book (!) poem, as ninety-nine percent of it has nothing to do with vampires. But the part that does concern us is when the hero, Thalaba, stands by his wife’s graveside, mourning her passing. A spirit appears and chides him, telling him God is not happy with him. But Thalaba recognises the spirit as a vampire, and kills it. Yeah, that’s it. Hardly worth it, huh?

Title: The Vampyre

Format: Poem

Author: John Stagg

Nationality: English

Written: 1810

Published: 1810

Impact: ?

Synopsis: Before we get to that, let’s just give this guy props, as he was blind, known in England as “the blind bard.” He’s also only the second English author to write about vampires, beating Lord Byron by three years. His poem concerns the worry of a wife for her husband, who is not looking the ticket. "Why looks my lord so deadly pale?/Why fades the crimson from his cheek?”

Midnight seems to exert its mystical power over the husband, too, as his wife bemoans how at that time “You sadly pant and tug for breath,/As if some supernat’ral pow’r/Were pulling you away to death?/Restless, tho’ sleeping, still you groan/And with convulsive horror start.”

The husband tries to explain: "Young Sigismund, my once dear friend,/ But now my persecutor foul,/Doth his malevolence extend/ E’en to the torture of my soul.” He tells his wife that his old friend is haunting him, visiting him at night, draining his blood. That’s not the worst though, as he sorrowfully tells her she’s next. “When dead, I too shall seek thy life,/Thy blood by Herman shall be drain’d!” But he tells her of a way to prevent this, basically by staking him when he dies. She stays by his side till he does pass, and then uses a lamp to frighten off the bloodthirsty Sigismund.

The next day, after she has told the town council what her husband has revealed to her, they break open Sigismund’s coffin and sure enough there he is: not decayed and full of blood. So they stake him and poor old Herman too, and the curse is broken.

I have some questions. First, if Herman knew how to get rid of that pesky Sigismund, why did he wait till he was at death’s door to tell his wife? Why not get himself released earlier, when he might still have regained his strength? And how did he come by this knowledge? Who told him how to break the curse? And while we’re at it, how did Sigismund get vampirised? All questions, it would seem, that will never be answered.

Title: The Giaour

Format: Poem

Author: Lord Byron

Nationality: English

Written: 1810/1811

Published: 1813

Impact: 4

Synopsis: The poem itself is an epic one, and deals with the Turkish practice of what I suppose we would refer to today as “honour killings”, and the Giaour of the title refers to an infidel or unbeliever. In the poem, having learned of the folklore during his Grand Tour of the east, Byron mentions the vampire, and alludes that the Giaour is condemned to the following fate for his crimes:

But first, on earth as vampire sent,

Thy corse shall from its tomb be rent:

Then ghastly haunt thy native place,

And suck the blood of all thy race;

There from thy daughter, sister, wife,

At midnight drain the stream of life;

Yet loathe the banquet which perforce

Must feed thy livid living corse:

Thy victims ere they yet expire

Shall know the demon for their sire,

As cursing thee, thou cursing them,

Thy flowers are withered on the stem.

Byron wrote in the notes his findings on vampire folklore while travelling through Europe:

The Vampire superstition is still general in the Levant. Honest Tournefort tells a long story about these ‘Vroucolachas’, as he calls them. The Romaic term is ‘Vardoulacha’. I recollect a whole family being terrified by the scream of a child, which they imagined must proceed from such a visitation. The Greeks never mention the word without horror. I find that ‘Broucolokas’ is an old legitimate Hellenic appellation—the moderns, however, use the word I mention. The stories told in Hungary and Greece of these foul feeders are singular, and some of them most incredibly attested.

The Author writes under the name of Trollheart.

To be continued…