The Men Who Sold the World: The Movers, Shakers, Givers and Takers of World War II

Part I: Deutschland Uber Allies

From Apathy to Apotheosis: The Making of a Monster

The Rise of Hitler and the Ensorcellment of Germany

Although there were many contributing factors to the war, and although Germany was ripe for revolution and revenge, it’s probably fair to say that, on the whole, the Second World War would never have broken out had it not been for its principal architect. Various science fiction stories have been written where someone goes back in time and kills Hitler, or the idea has merely been floated (“if you had a time machine and could go back to Germany in the 1930s would you kill Hitler?”) and it does seem likely that had he not been born, or had his life tended in other directions, the main impetus for what became the most massive global conflict in human history would not have been there, or if it had, nobody would have been willing to push it as he did.

So, while it may seem trite and cliched to say “without Hitler there would have been no World War II”, on balance it can be said to be the case. Which means that if we are to look for the reasons and the ideas that led to the war, we have to trace the life story of the man who would grow up resentful at his own government, ashamed of his country, and hungry for both power and a chance to set the scales straight, if not overload them on the side of his country.

But of course, one man cannot change history on his own, no matter how dedicated or insane he may be. Osama bin Laden could have done nothing without his Al Qaeda, Genghis Khan would have cut a pretty lonely and forlorn figure sweeping across the Mongolian Steppe on his own, and Vlad the Impaler? Well, he sure didn’t impale all those hundreds or thousands of victims by himself, now did he?

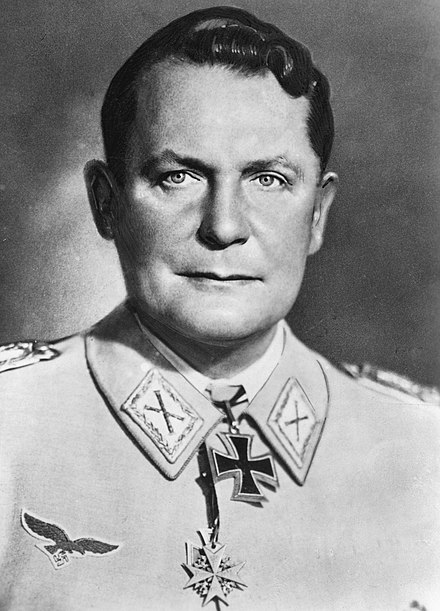

Just my typically oblique way of pointing out that even a demagogue like Hitler needed others to carry out his plans and execute (often literally) his orders, and as shown in, among others, History’s programme Hitler’s Circle of Evil, the man who would be ruler of the world made sure to surround himself not only with sycophants and like-minded killers, but men who were - in the context of the Reich - good at their jobs. Men without morals, scruples or the slightest shred of pity for their victims. Men who thought only of themselves and their Fuhrer. Men who pledged their undying loyalty to Hitler, even if almost all of them deserted him in the end. Men like Goebbels, Himmler, Goring and Bormann, Speer and Heydrich and Hess, all of whom helped, to one degree or another, bring about and prosecute the Second World War. We will be looking into their lives too as part of this feature.

But right now, it’s the top madman we’re checking out, to see how he grew from being a quiet, reticent boy into the man who would become forever synonymous with the word evil.

Adolf Hitler (1889-1945)

I: A Loser From Linz

It’s always been mildly amusing to me that Hitler, the archetypal fascist who demanded all Germans be “pure-bred Aryans” was nothing of the sort. Born in Austria, not Germany, he did not come from any noble family, in fact his father, Alois Hitler (originally Heidler) was a bastard, only legitimised (how? Do not ask me: I assumed an illegitimate child was always so) in 1876 at the age of 39. Adolf was born on April 20 1889, the fourth of six children, three of which did not survive. He was the issue of his father’s third wife, and lived with also two of Alois’s children by his second.

After his father had failed as a farmer, moving around from Austria to Germany and back, Adolf lost his younger brother Edmund to measles in 1900, and from that point his attitude changed; from being a conscientious, likeable child he turned inwards, becoming moody and fractious and withdrawn, constantly picking fights with his father and his teachers. When Alois scorned his son’s dream of becoming an artist and sent him not to the classical school Adolf wished to attend, but a bog-standard secondary school, (he later claimed) he deliberately did poorly there, in order to force his father to give it up and let him go to the art school. This never happened, even when his father died in 1903 and his mother allowed him to leave the school.

A German nationalist from an early age, Hitler refused to recognise or pay homage to the Hapsburg Empire, which controlled Germany and Austria, among other countries, at the time, already using the greeting “Heil”. In 1907 he wandered to Vienna where he tried to enrol at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, but was rejected on two occasions. His work was deemed “mediocre”, mostly in that he tended to draw or paint buildings but was unable to draw people, and it was suggested he instead apply to the Academy of Architecture, but as he had left school without finishing his term he did not have sufficient academic credits to allow this.

Perhaps the biggest blow to him in his young life was the sudden death of his mother, whom he had idolised, at the age of 47. Two years later, without her financial support he ran out of money and had to live in homeless shelters. While in Vienna he became what we would probably today call radicalised, as he listened to the hateful anti-Semitic rhetoric and ravings of certain figures who we will now discuss.

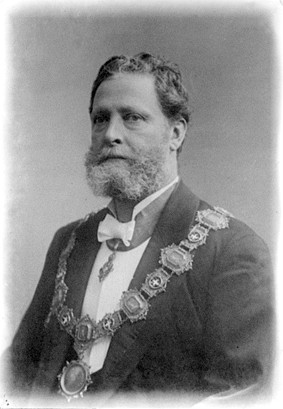

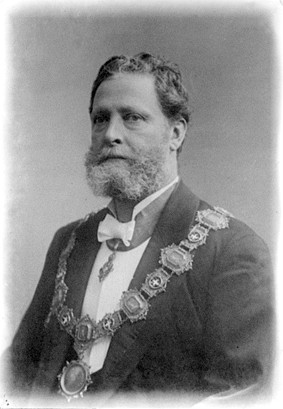

Karl Leuger (1844-1910)

Like many anti-Semites, Lueger was not above taking work from, and inspiration and patronage from a Jew, Dr. Igmaz Mandl, who was in fact his role model and advocate when he set up his lawyer’s practice in 1874. The fact that the man whom he would inspire to the greatest national and international hatreds and crimes against his people would mean that les than fifty years later Mandl would have been not only banned from practicing law, but would have been deported, killed or imprisoned, was never to be brought home to Lueger, as he died before Hitler came to power. A rabid Catholic who had no time for other religions and frowned on non-German speakers, he rose to become leader of the Unite Christian party and was elected mayor of Vienna no less than five times, four times of which he was thwarted by the emperor, Franz Josef, who did not like him and feared his revolutionary and anti-Semitic rhetoric, refusing to confirm him until finally his powerful party appealed to the Pope, who granted his mayorship (presumably over the protests of His Excellency) in 1897.

He proved a popular mayor, and indeed held the post (once confirmed) up until his death in 1910. He was credited with beautifying the city and improving its infrastructure, though his membership in the German National Party, which was notoriously anti-Semitic, seems to be where his views began to either change on, or harden against Jews. He courted the popular vote by raising “the Jewish Question”, a phrase which would return to haunt the Jews of Europe in the late 1930s and 1940s, and throw the shadow of the concentration camp across the continent, bringing the word holocaust, if not into our dictionaries then forever linked to the massacre of millions of innocents. An interesting parallel with Hitler’s later ideology, surely not coincidental, was that Lueger was very popular with Viennese women who, though they could not vote, were seen as the best method to indoctrinate their children into the party way of thinking, and also to influence their husbands how to cast their votes. He did not marry, and declared himself essentially married to Vienna, in a chilling future echo of how Hitler would characterise himself, despite being linked with one or two women during his life, one of whom he would marry just before committing suicide.

There is, however, evidence to suggest that either Hitler was chasing the wrong prey, or that he knew this, and cherry-picked the facts he wanted, the ones which were useful to him, from Lueger’s life. Historian William L. Shirer has gone on record to say that “his opponents, including the Jews, readily conceded that he was at heart a decent, chivalrous, generous and tolerant man.”[7] According to Amos Elon, "Lueger’s anti-Semitism was of a homespun, flexible variety—one might almost say gemütlich. Asked to explain the fact that many of his friends were Jews, Lueger famously replied, ‘I decide who is a Jew.’ If Lueger did indeed use the prevalent hatred for and anger against Jews to further his own position, this tactic was ignored by the man who would later look to him as an inspiration and quote his policies in his most famous book.

Whether intentionally or not, Hitler was not the only one influenced by Lueger’s views to push towards the advance of fascism. In Austria, Ignaz Seipal, Engelbert Dollfuss and Kurt Schuschnigg, all prominent politicians, would drive the country in a direction which would later serve Hitler’s need as he, at a single stroke, “liberated” Austria as one of his first pre-war acts.

Georg Ritter Von Schönerer (1842-1921)

Another of the hypocrisies of Hitler’s logic is that a man who was born into wealth and influence, and who worked for some of the richest and most powerful Jews in Austria, the Rothschilds, should have such an effect on him and help him shape his worldview. Where is the “ordinary German (or Austrian I guess) man” here? Where is the poor, oppressed, disenfranchised and downtrodden son of Germany? Not in Georg Ritter von Schönerer, that’s for sure! His father knighted by the same emperor who four times refused to confirm Karl Lueger as mayor, Georg’s early manhood did parallel Hitler’s in a way, in that the defeat of Austria in the Austro-Prussian War disillusioned him and set him on a course of political radicalism, railing against both the Jews and the Catholics (at least, I guess, he could be said to be an equal opportunities bigot!) and clamouring for the absorption of Austria into the German Reich.

More future echoes of Hitler when Schönerer’s party only accepted true Germans, forbade any sort of association of its members with Jews, and only allowed marriages if both could prove to be of true Aryan descent. In chilling addition, Schönerer was called Fuhrer by his followers, who saluted him with the phrase “Heil”! Schönerer laid the groundwork for a battle against the Jews, claiming that if they (Germans) did not kick the Jews out they would be ousted themselves. In a mini-foreshadowing of Kristallnacht, the night of rampant violence and murder that saw hundreds of Jewish properties burned or wrecked and many dead and injured in 1939, Schönerer ransacked the offices of a Jewish newspaper and assaulted its staff, in 1888, while a few hundred miles to the west Jack the Ripper was stalking the streets of London’s East End. Two dark presences, indeed, cloaking the emergence of a third, far worse, each spreading evil in their own way, one under cover of darkness and subterfuge, the other openly, and with general approval.

Interestingly, given that both were later favourites of Hitler, Schönerer and Lueger were rivals, the latter taking the chance to fill the power vacuum left behind when the former was imprisoned after the raid on the Jewish newspaper.

Martin Luther (1483-1546)

(Here, I’m just going to transcribe my account of the father of Protestantism from my History of Ireland journal, as I see no need to rewrite it in full. It may not all be relevant to this journal, but bear with me, as Luther is very much a minor player in the makeup of Adolf Hitler, but needs to be mentioned nonetheless.)

There can be no argument that in the time before, and even during the Renaissance, the Catholic Church was not only a major world power, almost the major world power, a huge player in politics, maker and breaker of kings, and the agency that called for retribution against the heathen with the Crusades, but one of the most corrupt organisations in the world. Successive popes set themselves up as kings, emperors or warlords (or all three), keeping standing armies and enriching their own coffers, more concerned with material wealth than spiritual salvation, while their priests and bishops preached exactly the opposite message to the faithful from the pulpits every Sunday.

A young German monk named Martin Luther had been watching all this misuse of power for some time, but the final straw for him came in 1516, when the Pope at the time, Leo X, sent an envoy to Germany to sell indulgences in order to finance the rebuilding of the church of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Indulgences were, essentially, get-out-of-jail-free cards for Christians, though scrub out the word free. For a payment, large or small depending on the sin to be expunged, penitents could purchase a letter signed by Leo which would then allow a soul held in Purgatory (transient state between Heaven and Hell) to be released into Heaven. Basically you were paying for the soul of your mother, father, child, wife, whoever, who had died, to be sprung from Limbo.

The phrase “As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from Purgatory springs” so enraged Luther that he wrote to the Pope, decrying the practice of indulgences, and asking, quite reasonably really, why a man so incredibly wealthy as Leo X, reckoned at the time to be one of the richest men in the world, if not the richest, had to rely on the contributions of the poor to rebuild a church when he had the money to do so out of his own pocket? Instead of answering this accusation, the Pope decided to brand Luther a heretic and excommunicated him, in the same way as he would deal with England’s upstart king a decade later.

But Luther would not be so easily silenced. He saw the rot in the Catholic Church, most especially at its venerated head, and the disrespect that the man supposedly chosen by God as His agent on Earth paid to the office, and he and his followers broke with Rome, splintering into their own religion, which though still Christian would be rabidly opposed to Catholicism. It was, of course, called Protestantism.

I’m not entirely clear what Hitler learned or used from his readings about Luther, whether it was merely a case of discrediting the Catholic Church, speaking truth to power and showing that absolute power corrupts absolutely (how very ironic if he should have taken that tack!) or whether he wanted to show how a poor - and most importantly, German - monk could rise to challenge the established order and essentially win, as even today the Christian Church is divided along deeply sectarian lines.

It’s also possible that he learned from Luther’s example how relatively easy it is to spread and disseminate a new idea, a radical idea. While arming Germany for another war, claiming the Fatherland was the pinnacle of human achievement and even anti-Semitism could hardly, in the context of history, be called radical, handing over power to one man, essentially abolishing the government and creating a dictatorship in a previously nominally democratic country surely was, and perhaps here is where Hitler learned the lesson already taken on board by Luther: get people angry enough - either against a real or imagined enemy - and you can take complete control of them. They will follow you to the ends of the earth, even if the final destination is a maelstrom of fire and destruction.

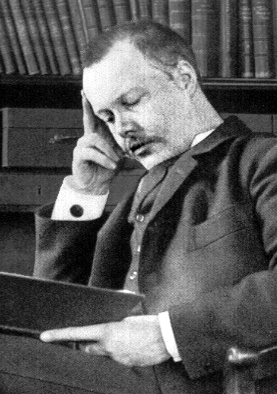

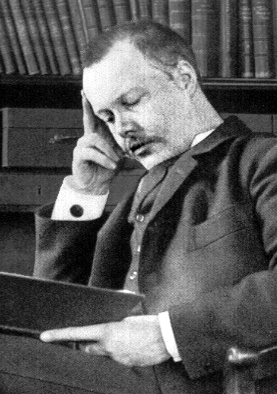

Houston Stewart Chamberlain (1855-1927)

Sure, there are many coincidences in history, and particularly in World War II, but it’s still interesting that he would be influenced favourably (in his view) by a man who a) was British (born, if actually lived most of his life in Germany) and b) possessed the same surname as the Prime Minister who virtually inadvertently helped him to power by refusing to believe Hitler would lie, that he wanted war, and that his word was worth about as much as, as the Americans say so charmingly, a plugged nickel. But Chamberlain (this one, not Neville) has been described as “Hitler’s John the Baptist” and so it is incumbent upon us to investigate him.

So let’s do that now.

Again born into power and influence, Chamberlain was the son of Rear-Admiral William Charles, but was a sickly child and sent to foreign climes for his health, starting in France and moving on to Spain and Italy. Influenced by people like Otto Kuntze and Carl Vogt, he became interested both in German culture and the idea of anti-Semitism, disowning England as having no place in his life, and even siding with the Irish in 1881 by describing the tyrannical land lords who oppressed the Irish peasantry (and whose intractability and naked greed had led indirectly to the Great Famine of 1848) as “blood sucking Jews”, even though they were Irish Protestants, and no more Jewish than I am. Although he had been a scientist - in particular a botanist - Chamberlain denied much science, theorising, for instance, that all the planets and heavenly bodies were covered by ice, and rejecting Darwinism (another dichotomy, as Hitler accepted and espoused Darwin’s theories and thinking) and the theory of evolution.

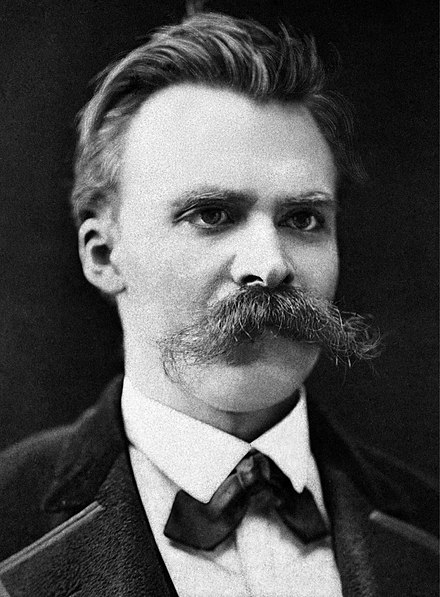

Richard Wagner (who we will be also looking into) seems to have been one of the biggest influences on Chamberlain’s life, his music causing him to change from speaking French (he detested everything about England, including the language) and start using the German tongue exclusively. In addition, he met a German woman, Anna Horst, whom he married, and his English upper class family’s objection to his marrying beneath his class only widened the divide between their country and what he now considered his; his failure to succeed in playing the stock market while living with her in Paris in 1883 further solidified his hatred of capitalism. You have to wonder, had he been successful would he had been so critical of the system? Becoming an author, he embraced the idea of “blood and soil”, the German racist idea of purity, and read Nietsczhe (again, we’ll look into him; we have to really) as well as writing of his joy that the emperor Friedrich III was dead, succeeded by his anti-Semite son, WIllem II, later to become Kasier Wilhelm.

Where he and Hitler may have diverged was that Chamberlain longed for and believed in an idealised, mythic view of a Germany that had never existed, basically one out of story books and fairy tales, and mythologised in Wagner’s music, much of which was based on Teutonic fables and sagas, while Hitler actually looked to history, to the great German kings and emperors of the past, wishing to emulate them. Chamberlain’s association with Wagner’s wife, Cosima, whom she came to consider as her surrogate son, did nothing to stem his anti-Semitic views, in fact it strengthened them considerably. Despite her patronage, though, Chamberlain could never escape from the reality that he was not German born, and so overcompensated by trying to make himself as German as he possibly could. To some extent, this could be said of Hitler too, though it seems after he rose to power his Austrian origins were conveniently fudged over and forgotten, though of course by then Austria was part of the Reich anyway.

Another divergence seems to come when Chamberlain discovered Hinduism and the “Aryan gods” (aryan literally “the light ones”), quickly concluding these were German, and adopting one of their symbols, the swastika; whereas Hitler would conveniently (to my knowledge anyway) discount Indians and blacks as inferior races of no value, Chamberlain believed there was much to learn from the Hindu gods, and the ancient caste system practiced by Hinduism, which “kept social inferiors firmly locked into their place” and fused humanity and nature, denying the hold of materialism. Right. Tell that to the Nazis as they were loading up half-tracks full of stolen artworks and jewels!

Chamberlain declared his preference for a dictatorship when he visited Bosnia and Herzegovina, under the control of the Austrian Empire, in 1891, believing dictatorship was the perfect equation of Wagner’s philosophy, “absolute monarch = happy people!” Not quite what the French thought, my friend, a century before this, and see how that worked out! His anti-Semitism growing like a cancer, and spreading like one, he had this cheery note about his house: However, we shall have to move soon anyway, for our house having been sold to a Jew … it will soon be impossible for decent people to live in it … Already the house being almost quite full of Jews, we have to live in a state of continual warfare with the vermin which is a constant and invariable follower of this chosen people even in the most well-to-do classes.

Interestingly, as Chamberlain moaned about the Boer War, with “whites killing whites as the great Yellow Danger” arose in the east, Cosima Wagner agreed thus: "This extermination of one of the most excellent Germanic races is so horrible that I know of nothing I have experienced which is comparable to it.” Well, her countrymen would soon change that, wouldn’t they? More confusion about what exactly was an Aryan, as Chamberlain included Celts, Slavs, Greeks, Latins and even some North Africans, whereas later Hitler and the Nazi party would define Aryan as German or Austrian, or German-born only. Bloody Nazis couldn’t even get straight who exactly they hated. Russians and French were out of the Aryan club though, polluted by foreign influences, while Jesus Christ was given a pass, as he could - according to our friendly neighbourhood anti-Semite Wagnerian, not be a Jew. He published all this nonsense as the century turned, in his Die Grundlagen des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts, or to give it its less wordy English name, The Foundations, a supposed history of the world, glorifying, not surprisingly, Germans and the Aryan race, and crediting them with every advance humanity has made.

Not to forget women, Chamberlain had no time for feminism, and preferred submissive women and believed they should know their place at the feet of their husbands and masters. He also claimed all the great writers, poets and artists as Ayan, including Shakespeare, Goethe, Da Vinci, Dante, Rembrandt, Homer and Martin Luther. Building on the writings of the French philosopher Arthur de Gobin****e, sorry Gobineau, he tasked the Jew with all the world’s wars, going all the way back to the Punic Wars in 146 BC and praising “Aryan Rome” for destroying (eventually) “Semitic Carthage”; blaming the Jews for their manipulation and control of the world’s financial institutions, and declared that the Jew wanted to “put his foot upon the neck of all nations of the world and be lord and possessor of all the earth.” This of course would be another of his ideas Hitler would take to heart, or at least use in his prosecution both of ethnic cleansing and the implementation of the Final Solution to the Jewish Question thirty years later.

Jewish conspiracies abounded in Chamberlain’s writings, including the idea that the Jew wanted to enslave all other races and be the master race (sound familiar?), that they had invented the Catholic Church as a “front” for Judaism, and that they had also invented both democracy and capitalism - both of which he despised - as well as, oddly, socialism, though this last was seen to be merely a diversionary tactic to funnel attention away from the damage wrought by Jewish financiers. Oh yes, and they had founded China as well. He even went further than Wagner, who believed Jews could gain redemption by converting to Christianity; Chamberlain was having none of this. For him, the solution to the Jewish question was simple and final, very final: all Jews everywhere must be utterly annihilated. No wonder Hitler loved reading his crap.

Nevertheless, it seems, to quote Louis in Interview With the Vampire, Chamberlain did not even have the courage of his convictions, as he did not actually advocate genocide against the Jews, but left the solution up to his reader, thereby abrogating responsibility for the coming Holocaust. It was in fact an admirer of his, building on his theories, who pushed the “Jewish Question” to what would have been seen by anti-Semitists as its logical conclusion. Josef Reimer propounded in his Ein Pangermanisches Deutschland (A Pan-Germanic Germany) in 1905 that Germany should invade and annex Russia, categorising the population into three separate classes - ethnic Germans, those capable of being “Germanised” and the hopeless cases, including Slavs and of course Jews, who were to be exterminated. Rather chillingly, much of this would come to pass before another four decades had passed.

When Chamberlain visited Britain in 1900, he was even more disillusioned with the land of his birth than he had been while away from it, accusing the Jews of having control of everything, abhorring the practice of raising “common folk” into the peerage and thus polluting (whatever remained of) the noble blood of England, and laying much of the blame for England’s, in his eyes, negative transformation at the feet of the then Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli, whom he vilified as “that Jew”, though Disraeli, while born into the Jewish faith, had become an Anglican from age twelve. Chamberlain’s racist and anti-Semitic and expansionist views brought him to the attention of Kaiser Wilhelm, with whom he became great friends, and whose ideas must have been shaped, at least in part, by Chamberlain’s views when Germany went to war just over a decade later. By the time World War I began though, and perhaps frustrated at being rejected from the German Army (he was 58 and in very poor health, partially paralysed: what did he expect?) Chamberlain declared that the Reich must “for the next hundred years or more” strengthen all things German and carry out “the determined extermination of the un-German”, believing that a German victory - which he fully expected - was the only possibility Britain had of being saved from the Jewish-controlled mire it had sunk into.

A man who seemed to want to have everything both ways, he advocated a return to his imagined “Merry old England” idea in Germany, an agrarian society where people worked happily while at the same time wishing Germany to become a huge industrial power and to exist under an iron dictatorship, having no time for democracy and believing, as already mentioned, it to have been an invention of the Jews. He despised the idea of a republic and wanted a monarchy to remain in control, though a militarist one answering to the army. He did not create, but helped get started, the “stab-in-the-back” legend/lie upon which so much of Hitler and the Nazi party’s self-justification for World War II would be based, by claiming there was a cadre of traitors within Germany, the “inner enemy” (which under Hitler would be referred to as “fifth column”) who were either Jews or were working with Jews to bring about the end of the war and Germany’s defeat and surrender.

And as is ever the case, evil attracts evil, and the dark circle closes, the ravenous and insatiable Ouroboros chewing on its own tail…

Shattered by Germany’s unthinkable, to him, defeat in the First World War, and increasingly paralysed (and unhinged), mostly confined to his bed, Chamberlain watched with interest the rise and progress through the ranks of an Austrian politician who had come to his notice. In 1923 Chamberlain and Hitler met, and later Chamberlain joined the Nazi party, becoming one of Hitler’s biggest supporters and endorsers. The admiration was mutual; Hitler proclaimed The Foundations as “the gospel of the National Socialist Movement”, while Chamberlain had this to say about der Fuhrer:

Because he [Hitler] is no mere phrasemonger, but consistently pursues his thought to an end and draws his conclusions from it, he recognizes and proclaims that one cannot simultaneously embrace Jesus and those that crucified him. That is the splendid thing about Hitler—his courage! … In this respect he reminds one of Luther. And whence come the courage of these two men? It derives from the holy seriousness each has for the cause! Hitler utters no word he does not mean in earnest; his speeches contain no padding or vague, provisional statements … but the result of this is that he is decried as a visionary dreamer. People consider Hitler a dreamer whose head is full of impossible schemes and yet a renowned and original historian called him “the most creative mind since Bismarck in the area of statecraft.” I believe … we are all inclined to view those things as impractical that we do not already see accomplished before us. He, for example, finds it impossible to share our conviction about the pernicious, even murderous influence of Jewry on the German Volk and not to take action; if one sees the danger, then steps must be taken against it with utter dispatch. I daresay everyone recognizes this, but nobody risks speaking out; nobody ventures to extract the consequences of his thoughts for his actions; nobody except Hitler. … This man has worked like a divine blessing, cheering hearts, opening men’s eyes to clearly seen goals, enlivening their spirits, kindling their capacity for love and for indignation, hardening their courage and resoluteness. Yet we still need him badly: May God who sent him to us preserve him for many years as a "blessing for the German Fatherland!

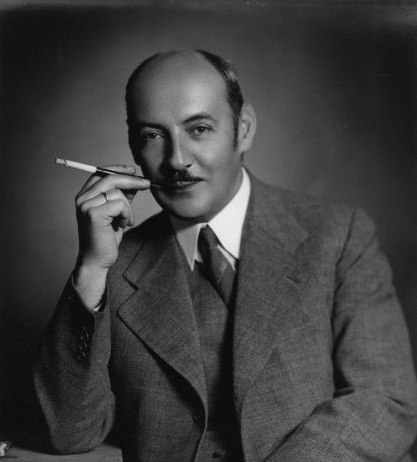

Even when Hitler was imprisoned (yeah) as a result of the failure of the 1923 Munich Putsch, Chamberlain did not lose faith in him, and campaigned vigorously for his pardon and release. In the event, Hitler served only seven months of what was supposed to be a two year sentence before being freed into an atmosphere of general disinterest. Houston Stewart Chamberlain died in 1927, having made, among others, Hitler and an impressionable Josef Goebbels fans, and the former was present at his funeral.

Five years later, as Nazism began its inexorable rise to power, a worried Carl Von Ossietzky, journalist wrote “Today there is a strong smell of blood in the air. Literary anti-Semitism forges the moral weapon for murder. Sturdy and honest lads will take care of the rest.”

It wouldn’t take long for that prediction to come true.