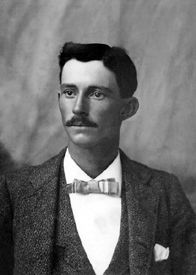

John B. Jones (1834 - 1881)

Another who fought for the South in the war, Jones was born in South Carolina but moved with his family when four years old to Texas, where he would spend the rest of his life. He achieved great fame in the Civil War, rising to the rank of Adjutant in only a month and later Adjutant-General. He took defeat hard, not surprisingly, as his service was now seen more or less as an act of treachery and rebellion, and there was neither thanks nor glory awaiting him at the war’s end. He left America, travelling to Mexico and Brazil with some half-baked idea of setting up a colony for Confederates, but it of course came to nothing and he returned to Texas, where he was elected to the State Legislature. As Texas was by now in the process of being returned to the Union, he refused to take the seat.

His chance to shine though came in 1874, when he was appointed by the governor as Major of a battalion of the Texas Rangers, and with six companies under his command he led attacks on Native American tribes such as the Apache, Comanche and Kiowa before being sent to Lampasas to try to deal with the Higgins-Horrell feud which had been going on for nearly four years at that point. Managing, in a sneak attack, to catch all the gang and arrest them, Jones then proved to be more than just a hard-headed tough old soldier, as he successfully negotiated a truce between the two clans. He next turned his attention to the apprehension of the notorious train robber Sam Bass and his gang, and after a four month chase he finally ran them to ground at Round Rock, where he shot and wounded Bass, who would die of the injury a few days later.

Jones died of natural causes in July of 1881, still in command of his Texas Rangers battalion, his exploits earning him a place in the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame.

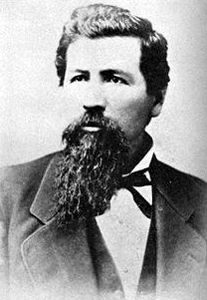

“Big” Dave Updyke (c. 1830 - 1866)

Another bad lawman, Updyke was the black sheep of his family, and after a stint driving stagecoaches and another spent in Columbia, he returned to the USA to join in the gold rush that had sprung up in Idaho state. He was successful here, earning enough from his claim to allow him to buy a livery stable in Boise, which is where his life, which had up until now been law-abiding, took very much a left turn. His stable began to become a meeting place for all the local desperadoes - whether he courted them or just fell in with them I don’t know - and before long he was consorting with some of the baddest men in that part of the country. His election to the post of Sheriff in 1864 did nothing to arrest (sorry) his slide towards criminality, in fact it had the opposite effect, as it put him in a position to turn a blind eye to, or often even participate in robberies orchestrated by his new friends.

So well known was his connection to the outlaws that they began to be known as “Updyke’s Gang”, though there was no proof that he was part of their enterprise. Realising that the only real threat to his power was a recently-formed vigilante group out of Payette River, about thirty miles outside of Boise, he vowed to disband it, to the anger of the citizens of Ada, who relied upon them - as they could not trust the sheriff to look after their interests - to keep them safe from robbers and murderers. Going completely against the wishes of the people he was supposed to protect, he in fact planned to have the members of the vigilante group (or vigilance committee, as they were often known) shot, claiming they had resisted arrest.

Word however was sent to the Payette folk of the planned treachery and they were ready for Updyke and his men, outnumbering them two to one. Forced to negotiate, the corrupt sheriff allowed the Payettes to return to town to answer the charges against them, and allowed them to keep their weapons. The charges were dismissed, and the vigilantes went free, but Sheriff Updyke had, in the words of Charles Montgomery Burns, made a powerful enemy, and the Payettes, who had long suspected Updyke’s involvement in the crimes that took place in the county, began to watch him closely.

They didn’t have to wait for very long, as Updyke and his criminal buddies were always on the lookout for easy prey, and they didn’t come much easier than the local stagecoach, passing through Pontneuf Canyon on its way from Montana to Utah, which was known to transport gold as well as passengers. The gang was co-led by Updyke with a desperado called Brockie Jack, who was actually on the run, having broken out of an Oregon prison, while the third member of their gang, Fred Williams, had been detailed to ride along with the stage to ensure there were no slip-ups, and to make certain it carried the big strongboxes of gold that were being shipped down from the Montana mines. He would desert the coach when it stopped near the spot where later it would be ambushed. No doubt Updyke’s experience as a stage driver in his younger days helped the gang plan their strategy.

The raid did not quite go according to plan, unless the gang intended killing everyone on the stage, and I have to believe they were more interested in getting the gold than slaughtering the passengers, but one of them was armed and put up a fight, leading to a sudden explosion of gunfire and when the smoke cleared all the passengers were dead. Nonplussed, the thieves collected their loot and headed off, but were pursued by the Payette vigilantes, who caught two of them, one shot down when he resisted arrest, the other hanged. Both men were said to have been almost penniless at the time, leading me to believe either that they had received a smaller share of the haul or had spent it very quickly, as this was only weeks after the raid.

Updyke evaded arrest, skipping town and heading to Boise City, but he had no power here and the citizens were organising their own vigilance committee. He stayed there until spring but eventually fled, along with another outlaw, John Dixon. Unaware that a posse was hot on their heels, the men stopped to rest at a cabin along the way. Taking them by surprise in the night, the vigilantes took the two men prisoner and the next morning they were hanged. No trace of the stolen gold was ever found - Updyke had a mere fifty dollars on him when he swung - and its whereabouts remains a mystery to this day.

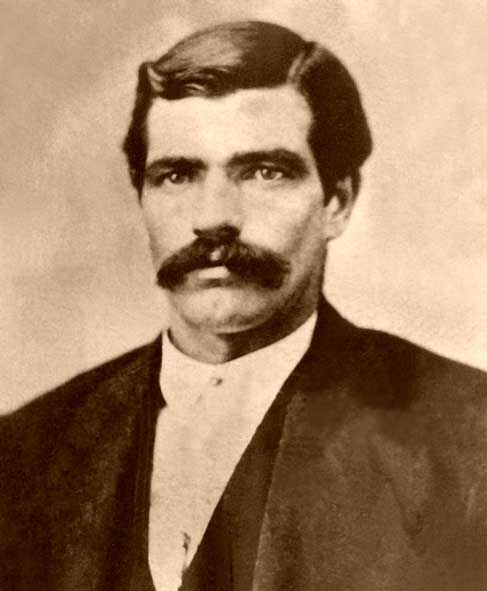

Seth Bullock (1849 - 1919)

Canadian born, with an English father and Scottish mother, Bullock ran away from home at sixteen and went to live with his sister in Montana, but not for long, as she sent him back home to his parents. Two years later he was gone again, and this time to stay. Two years after that he was elected to the Montana Senate, and helped create the famous Yellowstone National Park. Elected sheriff of Lewis and Clark County in 1874, he went into business with another man as a hardware merchant, and though he married the next year he sent his wife home to Michigan when he and his partner headed to Deadwood, South Dakota, to try their luck there.

And here we see that, despite my contention as to the unlikelihood of some stranger riding into town and becoming the local law enforcement official, this seems to have been exactly what happened to Bullock and his partner. Shows what I know!

Arriving in Deadwood, the two men discovered it to be a lawless place, with rowdy miners, cowboys, outlaws and prostitutes running wild, and nobody in charge. On the day they arrived, the famous Wild Bill Hickok was killed, and the townsfolk were demanding someone pay. Law and order needed to be established in Deadwood, and so their first marshal was appointed, but he did not last long, gunned down in an ambush less than two weeks later. Deadwood was really just a mining camp at this point, but when it was incorporated into the newly-formed Lawrence County, Bullock was elected as its sheriff, with authority too over the territory of South Dakota.

Bullock proved to be different to most sheriffs of the time. Though he appointed fearless deputies who helped him clean up Deadwood, it’s reported that he never shot a man during his time there, being able to, according to his grandson, “outstare a mad cobra or rogue elephant”, and his calm, brooding manner usually unnerved most gunhands who surrendered without firing a shot. As Deadwood began to settle down, Bullock sent for his wife and daughter, meanwhile he was promoted to US Deputy Marshal, and in 1884 met future President Theodore Roosevelt for the first time. The two men got on great, and would remain lifelong friends. When his hardware store burned down ten years later, Bullock took the opportunity to replace it with Deadwood’s first hotel, and the humbly-named Bullock Hotel quickly became the place to stay. It was certainly luxurious for the time, with three floors with a bathroom on each, steam heat throughout its sixty-four rooms. It still stands today.

Given his friendship with Roosevelt, it was no surprise that Bullock signed up with the Rough Riders when the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, but the war was over so quickly that he never got to see service. He did however ride in Roosevelt’s inaugural parade in 1905 along with a group of fifty cowboys, including the legendary Tom Mix. Following his taking office, the new president promoted Bullock to the post of US Marshal for South Dakota. The two men would die within months of each other, both passing away before 1919 was out. Seth Bullock was buried alongside Wild Bill and Calamity Jane, in Mount Moriah Cemetery.