Cowboys. The word conjures up so many images, from playing cowboys and indians as kids, to western movies, cowboy play suits, and cowboy-themed events such as (shudder) line dancing. Most of us from a certain age have been brought up on the idea of desperados riding into town and causing trouble, the sheriff rounding up a posse and then giving chase, of gunfighters facing each other in the street - “Draw, you worthless son of a bitch!” - and trains being robbed. Most of what we have to go on comes of course from Hollywood, who made it their business to make what became known as the Wild West as romantic and adventurous, and as exciting and attractive as possible. John Wayne saves the swooning girl from the nasty Indians, when in fact John and his people should never have been there, but Americans don’t need Hollywood reminding them that their entire history is built on bloodshed, on rape and murder, on lies and betrayals, the forced resettlement of an entire race of people, ethnic cleansing on a vast scale before the phrase was even coined.

And one thing Hollywood doesn’t give the punters is that which they don’t want. So a false, rosy picture of the Old West was created at MGM, Warner Bros and other studios, and men who knew nothing about the history of the time they were paid to portray grinned, spat, shot and glowered their way through countless western movies, always eager to assure the American public that they were God’s chosen, they were in the right, and the enemy had to be defeated. So what if the Indians - now called Native Americans in these times of political correctness, a bit late if you ask me - had lived on these lands for generations? So what if by mining and building and hunting the white man was destroying the very livelihood of a people, angering their gods and condemning them to live on reservations for the rest of their lives, and those of their descendants? America was all about progress, and he who got in its way could expect no mercy.

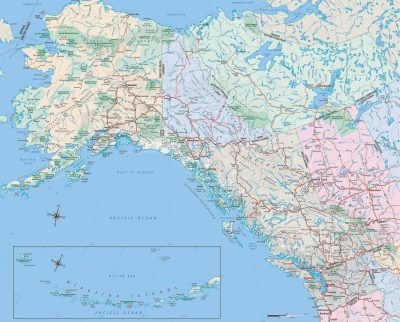

But this isn’t just a dig at the way we white folks treated the Indians, though that will form much of the framework of certain parts of this history. I mention it only because, while I will be recounting and paying tribute to the courage and daring of the men and women who opened up the West, those who explored and discovered, those who settled, those who built towns and railroads and those who kept law and order, I want it understood that all of this development of a country came at a price, a high price, and it should be borne in mind that, like, I suppose, any real conquest or colonisation, the American West (as opposed, let’s say, to the Indian West, or if you prefer, the White Man’s West as opposed to that of the Red Man) is built on the bones of men and women who feared the arrival of the White Man, and with good reason; they knew dark things were presaged the first time moving clouds of dust resolved into caravans of covered wagons, bringing the new settlers into the West, the men and women who would take their lands, destroy their holy places, and reduce them to a footnote in the country’s history.

Like most boys at the time, I was always interested in and fascinated by cowboys and the Wild West, and like most boys at the time, I swallowed the lies Hollywood and TV shows fed us, believing the “brave” cowboys were defending the towns against the “savage” Indians, and that really, as ever has been the case, white was right. It was only later, as I began to grow up and question things, that the true state of affairs began to make itself known to me, and then as now, a deep dark shame has always stayed with me over what my race did in the name of expansion, politics and power, and of course, greed. It’s a familiar and oft-repeated tale in the history of exploration - which often goes hand in hand with conquest - and a good reason why strangers always spell trouble for the natives.

But before anyone misunderstands me, I don’t hold the Indians blameless. They were savage, they were cruel, some of them were warlike, though not by any means all. Mostly, of course, when and if they they warred it was among each other, tribe against tribe, but when their lands were threatened by the new invaders from the east, most - though not all - banded together to fight the common enemy. This was not good news for homesteaders, cattle barons or railroad workers, and in time of course led to the infamous Indian Wars, where there were certainly enough atocities on both sides to go around. But if anyone was the aggressor, it was us (unless you’re an Indian/Native American reading, and if so, apologies) - left alone, surely, the Red Man would have caused no trouble to the colonists of the east: he probably couldn’t have. Even then, the technology, to say nothing of the sheer weight of numbers in the many cities along the eastern seaboard of America would have made it impossible for an Indian invasion. Nor, really, do I believe they would have wanted to have attempted such a campaign. Why would they? Their lands, the lands of their ancestors, their shrines and holy places, the very mountains and rivers they revered, all the resources they needed, the game they hunted for food and clothing were all abundant in the West. What would have been the point of riding east, to take on a far superior and well entrenched foe?

But when your land is under attack, most men and women fight back. Unfortunately, when your enemy vastly outnumbers you, has superior weapons and the technology and resources of a continent, you’re bound to lose. America may once have been the land of the free and the home of the brave(s), but no longer. How the West was won was through all but total annihilation of the other side. Hitler would have been proud.

So this is what it’s going to be like, is it? Moan, moan, moan, America murdered the Indians, grabbed their land, built on deceit, home of the brave etc etc? Nah. I try not to preach in my journals (can’t really find room for the pulpit, you see) and all I wanted to do in this introduction was outline the fact that I will be, so far as possible, looking at this from both sides, not just that of my own race. Among the books I’m using to research this is one called The Harlem Renaissance in the American West: the New Negro’s Western Experience by Cary D. Wintz and Bruce A. Glasrud and Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West by Dee Brown, as well as selections from the series Legends of the Old West including biographies of such Indian figures as Sitting Bull (Ronald A. Reis) and Geronimo and Crazy Horse (Jon Sterngass). I hope, with some luck, to also delve deeper into the Indian story and unearth some lesser-known figures I can tell you about.

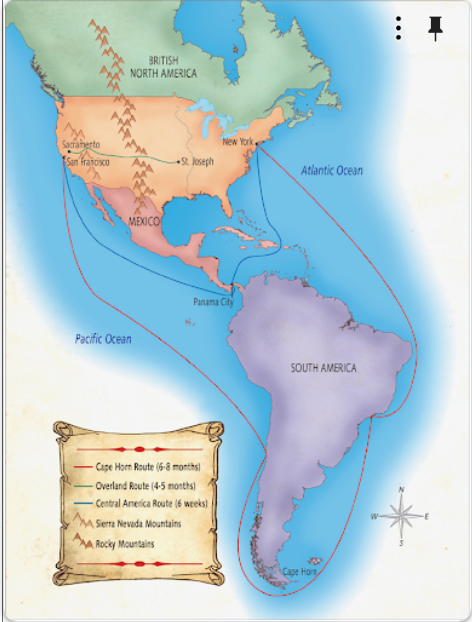

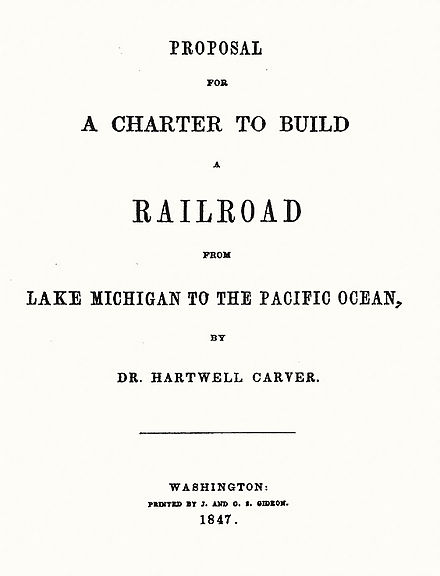

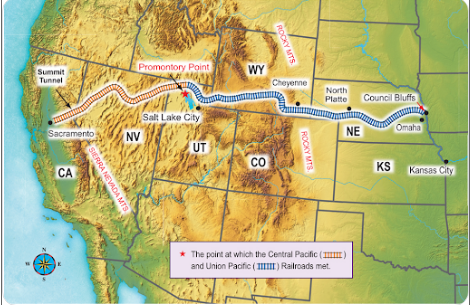

But mainly I’m going to be exploring the Old West, not as Hollywood would have us believe it was, but as it actually happened. I’ll be reading - and writing about - the lives of people both ordinary and extraordinary, those who “built the West” and were feted for it in history, and those who were perhaps ignored. I’ll be looking into relationships between not only the Indians and the settlers/army, but also the various Indian tribes, the Chinese, Irish and other workers who slaved (and many of whom gave their lives) to build the transcontinental railroads that would link up America, helping east meet west and finally and once and for all creating the United States of America in its fullest sense. I’ll of course be sketching profiles of the gunfighters, train and bank robbers, cattle barons and the men who kept, or tried to keep law in a lawless land.

I’ll be delving into the major battles - but only barely skirting the Civil War, as that’s too huge a subject to tackle here - feuds, trade wars, rivalries and ventures such as gold mining and of course railroad building, examining the changing landscape as new routes were discovered and settlements became towns, then cities, and how major firms such as Colt and Jack Daniels made their name in this period. What was it really like to be a cowboy? Or a rodeo rider? Or a woman in these perilous times? What role, what importance was education given? How about religion? How bad was racism, and how blurred were the lines between “good” and “evil”, on both sides of the divide? We’ve all heard of the US Cavalry massacring “innocent” Indians: what about the vile deeds perpetrated against the ordinary folk who came to settle the land? Did Indians really scalp people? Did showdowns take place out in the dusty streets after some bust-up about a card game? How much of what we know is fact, and how much made-up Hollywood fiction?

Saddle up, pardner, and make sure that horse you got is fresh, you hear? We got us a long trail ahead, and the prairie don’t have no mercy for those who don’t lay their plans mighty careful.

) I was disappointed when visiting the State of Texas not to see horse riders downtown on the main roads.

) I was disappointed when visiting the State of Texas not to see horse riders downtown on the main roads.