Folk singer and social justice advocate Buffy Sainte-Marie has denied allegations that she misled the public about her Indigenous ancestry, after a Canadian documentary questioned the “shifting narrative” surrounding her Cree roots.

On Friday, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s investigative wing, the Fifth Estate, published an investigation into the singer’s ancestry, alleging her life story is part of a broader narrative “full of inconsistencies and inaccuracies”.

The controversial report from the national broadcaster comes after a string of high-profile “pretendian” allegations that raise broader questions about the appropriation of Indigenous identity.

Sainte-Marie’s website describes herself as a “Cree singer-songwriter” who is “believed to have been born” in 1941 on the Piapot First Nation reserve in Saskatchewan. She was reportedly taken from her biological parents when she was an infant and raised by a white family in the US. The singer has previously said that a hospital fire destroyed her birth records.

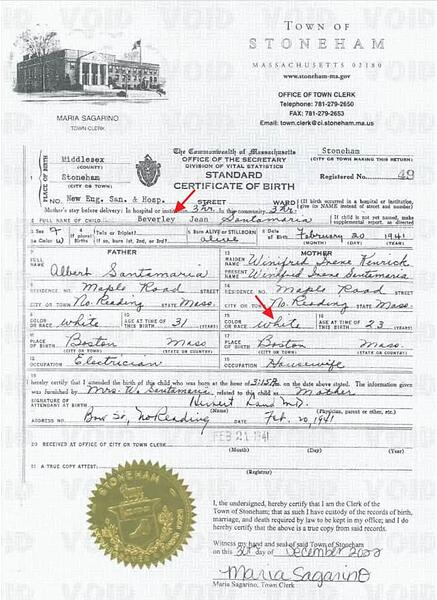

But the CBC, citing interviews with Sainte-Marie’s family and a birth certificate, suggests there is evidence she was born in Stoneham, Massachusetts, and has no Indigenous ancestry.“She wasn’t born in Canada … She’s clearly born in the United States,” Heidi St. Marie, daughter of Sainte-Marie’s older brother, Alan, told the CBC. “She’s clearly not Indigenous or Native American.”

Ahead of the report, Sainte-Marie released a statement on Thursday, calling the allegations “deeply hurtful”.

“I have always struggled to answer questions about who I am,” she said. “Through that research what became clear, and what I’ve always been honest about, is that I don’t know where I’m from or who my birth parents were, and I will never know.”

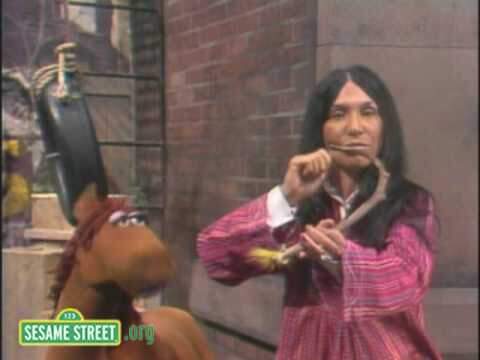

Buffy Sainte-Marie, CC is an American–Canadian singer-songwriter, musician, composer, visual artist, educator, pacifist, and social activist. While working in these areas, her work has focused on issues facing Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Her singing and writing repertoire also includes subjects of love, war, religion, and mysticism. She has won recognition, awards and honours for her music as well as her work in education and social activism. In 1983, her song “Up Where We Belong”, co-written for the film An Officer and a Gentleman, won the Academy Award for Best Original Song at the 55th Academy Awards. The song also won the Golden Globe Award for Best Original Song that same year. In 1997, she founded the Cradleboard Teaching Project, an educational curriculum devoted to better understanding Native Americans.

In her early twenties she spent a considerable amount of time in the coffeehouses of downtown Toronto’s old Yorkville district, and New York City’s Greenwich Village as part of the early to mid-1960s folk scene, often alongside other emerging Canadian contemporaries, such as Leonard Cohen, Neil Young, and Joni Mitchell.

In 1963, recovering from a throat infection, Sainte-Marie became addicted to codeine and recovering from the experience became the basis of her song “Cod’ine”, later covered by Donovan, Janis Joplin, the Charlatans, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Man, and Gram Parsons. Also in 1963, she witnessed wounded soldiers returning from the Vietnam War at a time when the U.S. government was denying involvement – which inspired her protest song “Universal Soldier”, released on her debut album It’s My Way on Vanguard Records in 1964, and later became a hit for both Donovan and Glen Campbell.

Sainte-Marie was subsequently named Billboard magazine’s Best New Artist. Some of her songs addressing the mistreatment of Native Americans, such as “Now That the Buffalo’s Gone” (1964) and “My Country 'Tis of Thy People You’re Dying” (1964, included on her 1966 album), created controversy at the time. She sang the theme song of the movie Soldier Blue (1970) and sang the opening song “The Circle Game” (written by Joni Mitchell in Stuart Hagmann’s film The Strawberry Statement (1970).

To say that I am astounded at the allegations is an understatement. Buffy Sainte-Marie’s activities and music of the 1960’s were part of my alternative “tertiary education” … sex, drugs, rock’n’roll … and protest … ![]()

Maintaining a lifetime of “pretence” and achievement is probably more common than I know but the only example that springs to my mind is “Grey Owl”: