What makes someone kill? I’ll be damned if I know, and in this journal this is something we will not be investigating. I’m no psychiatrist, or psychologist, or anything else beginning with psy, and I have really no actual interest in finding out what makes these monsters tick. This will be the history of serial killers, from the earliest I can track down right up to, sadly, today. Given that we’re dealing with real people here, who may still have relatives who remember either the victims or the murderers, or we could also be talking about people who survived serial killers, it’s important, I feel, to take this a lot more seriously than I tend to with my other journals. So in respect and deference to the dead - and even the incarcerated, to some degree - I’ll be reining in my usual off-colour humour and making few if any jokes. Well, maybe. We’ll see. Sometimes a bit of light among the darkness is what’s needed. We’ll take it on a case by case basis, almost literally.

What I will be doing will be cataloguing the whole history of men and women who have, down through the decades and even the centuries, found it permissible to kill, and to kill again, and again. I’ll be running a timeline as usual, looking into not only the killers but their victims, the investigation into their crimes, and the men and women who finally brought them to justice, if brought to justice they were. As the logo says, beware if you are squeamish, as there will be no holds barred here, either graphically or in words: to understand the often horrifying nature of some of the killers here it will be necessary to describe in detail mutilations, abuses, tortures and so on, and I won’t be shying from those, and while I won’t be gratuitously putting up gory pictures for the purposes of titillation, where deemed necessary or appropriate I will use crime scene photos and other material available to me.

It should be clear - but I’ll make the point anyway - that I am in no way intending to glamourise or afford celebrity to these people, though in terms of the latter most of them will have attained that anyway during their murder spree, their trial or their execution. I can’t quite approach this with a totally dispassionate eye though either, but will do my best to avoid commenting on or moralising upon any of the crimes. I can’t promise to stick to that - some of them will be very harrowing, I have no doubt, and I may have to speak about them, editorialise as it were, but I will try to keep it brief. (Yeah, some chance, I know…)

Why have I suddenly become interested in serial killers? Blame my sister Karen. She’s always been fascinated by forensics and I’ve lost count of the amount of times I have had to read her accounts of this murder or that murder, and eventually I just thought it might be an interesting subject to research in depth.

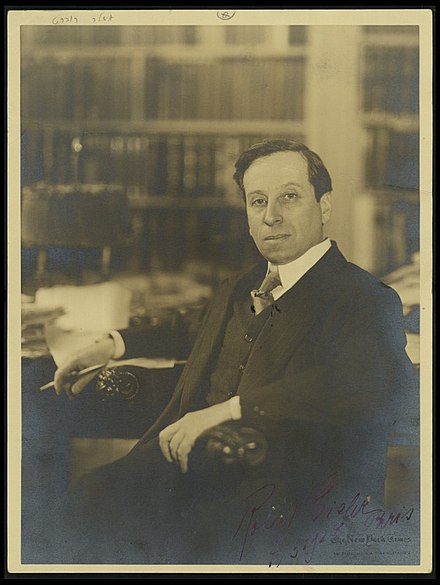

Robert Ressler (1937-2013)

Before we get into the timeline however, and start plumbing the darkness, let’s look at some of the pioneers who ensured serial killers would be easier to catch, or at least that they could be identified as same.

This is FBI agent Robert Ressler, who is generally credited with the coining of the term serial killer, although he called it serial homicide in a lecture given in 1974 at the Police Academy in Hampshire, UK. Now, I should make it clear that there is disagreement on whether he was the first to use the phrase, and we will be looking at the other candidates shortly. But whether he is responsible or not, he certainly developed and honed the idea of a criminal profiler, so prevalent today in real life and also in crime fiction. Already as a child he was interested in serial killers, and when posted with the US Army to Aschaffenburg in Germany from 1957 to 1962 he solved many crimes as head of a Military Police (MP) unit.

In 1970 he joined the FBI’s Behavioural Sciences Unit, which became the model for the department in the TV crime series Criminal Minds, with a slight change of name. He helped set up Vi-CAP, the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program, which is a database of unsolved homicides cross-referenced with the m.o (Modus Operandi, or method of operation) of known serial killers, to allow police to identify possible serial killers striking in new territories where their crimes may not be known. Having interviewed thirty-six serial killers himself, Ressler was pretty familiar with their methods, and had worked on the cases of famous (or infamous) murderers such as Jeffrey Dahmer, Ted Bundy and Richard Chase, known as the Vampire of Sacramento.

Ressler retired from the FBI in 1990, though he continued to consult and help in the cases of serial killers in the UK and South Africa, wrote books on the subject and also lectured at police academies, affording the new recruits his considerable expertise in their continuing fight against crime. He died in 2013 at the age of 76.

Pierce Brooks (1923-1998)

A legendary figure in the LAPD, Brooks set up the NCAVC - The National Centre for the Analysis of Violent Crime - and was instrumental in developing Vi-CAP. He worked on the “Onion Field” case, the kidnapping of two police officers in Hollywood in 1963, and the subsequent killing of one, and was described by his partner, Dan Bowser, as the “closest thing I ever saw to Sherlock Holmes.” Brooks joined the LAPD in 1948 and after serving with vice, narcotics and homicide he petitioned the department in 1958 to buy a computer to help him in his identification of the crimes of serial killers, having inherited the interest from his father, who had scoured the newspapers looking for similar crimes as the ones he had read about, believing “there’s no way this guy only did this once”. Reflecting both the shoestring budget of the LAPD at the time and the cost of computers in the late 1950s, his request was turned down because “they cost half as much as city hall and are half as big”.

By the time computers had become more affordable (and didn’t take up a whole room) he had already retired from the LAPD, but he testified at Congress as to how computers could be used to track and identify crimes and bring serial killers to justice. Like Ressler, he too became a consultant after retiring, offering vital insight and assistance in high-profile cases such as the Green River Killings and the Atlanta child murders.

Others who were instrumental in the creation of the processes by which serial killers could be detected and caught, or who originally used and may have coined the term include

Ernst Gennat (1880-1939)

Director of the Berlin Criminal Police, Gennat was exposed to criminality from an early age, when he lived with his parents in the staff housing of a correctional facility in Berlin. It doesn’t make it clear, but I’m going to assume that this was because his father worked at the facility. Gennat served for thirty years and was acknowledged as one of the most gifted and successful criminologists in Germany. Entering the police service in 1905 he was quickly promoted, and I mean quickly! Two months later he had progressed from detective assistant to criminal detective. Unfortunately, his criticism of the department - which lacked even a basic homicide division - kept him from further advancement until the reorganisation of the force in 1925 , whereupon he established the much-needed homicide division and was promoted to lieutenant inspector.

Under his leadership the new department thrived, and was soon solving almost 95% of crimes. Gennat took on the cases of two of Germany’s most infamous serial killers - coincidentally perhaps, both being identified in their code names as vampires - Peter Kürten, the “Vampire of Dusseldorf” and Fritz Haarman, the “Vampire of Hanover”. It was while writing about the former in his book Die Düsseldorfer Sexualverbrechen that he is said to have coined the term Serienmörder or serial killer. Gennat also developed the science of profiling to an art. He worked under Hitler but remained aloof from the Nazi Party, dying a mere two weeks before the onset of World War II.

We also have Robert Eisler (1882-1949), a polymath and connoisseur of mythology, who wrote a book in 1948 (one year before his death) entitled Man into Wolf: An Anthropological Interpretation of Sadism, Masochism and Lycanthropy, in which he used the term “serial killing”. He was a man who would know about such things, having spent two years in German concentration camps during the war.

Or how about John Brophy, (1899-1965), an Irish writer who used the term in his book The Meaning of Murder 1966.

Whoever coined the phrase originally, it’s generally accepted that it only came into popular use during the Atlanta Child Murders in 1981 when it was used in an article in the New York Times. By the end of the following decade it was a familiar and frightening term in use all across America, and known all over the world.

) and decapitated

) and decapitated