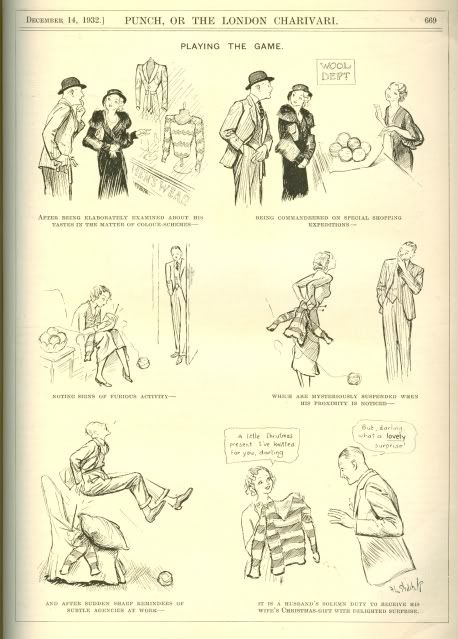

1932: Maintaining Harmony in the Home

This charming little scene is very much of it’s time but modern, more complicated, equivalents certainly exist. The advice was sound enough as are today’s examples.

1932: Maintaining Harmony in the Home

This charming little scene is very much of it’s time but modern, more complicated, equivalents certainly exist. The advice was sound enough as are today’s examples.

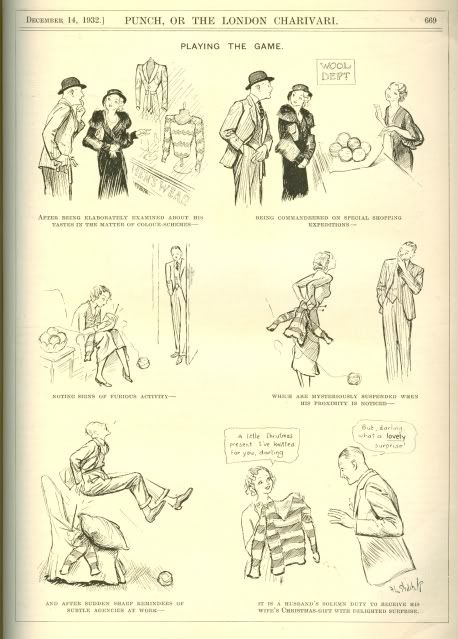

1932: Grownups Are Difficult to Understand

Unlike most jokes in Punch this scenario is entirely plausible. This is a well-heeled family. We note that there are two maids in attendance at this festive meal.

The younger daughter has failed, through no fault of her own, to understand the niceties of the situation. She has heard the family discussing Auntie’s visit before her arrival in which she was described as a burden that has to be borne. Now she has clearly heard her father toasting those who are loved. To her it is obvious that Auntie is not included and she wants to repair his omission. At that moment her father had not intended to exclude this troublesome relative from his general good wishes.

As a result she is going to commit a serious faux pas which will be very difficult to explain away. As she grows up she will have to learn how to navigate some of the subtleties involved. People do not always say in public what they think in private. She herself had failed to live up to this maxim which she had not yet learned.

Introducing 1914

I have no more cartoons to offer from 1931 and 1932. I have decided to go back in time to 1914. My source is a bound volume for the second half of that year. By starting at the beginning of July we are able to witness the last few short weeks before the outbreak of ‘The Great War’, as it used to be called. The cartoons from those weeks illustrate perfectly the total unawareness of the horrors to come. Britain had not been involved in a European war since the defeat of Napoleon 99 years previously. The Boer War (which was not in Europe but was against an ethnic European enemy) should have provided a serious warning but it hadn’t been heeded.

1914: It Jolly Well Belongs to Her!

We note that there is nothing hesitant in the way that she asserts her rights. Her pew, which she pays for, is a measure of her standing in the community. I really doubt that 100 years ago the readers of Punch would have thought of Mrs Pilkington-Haycock as a snob. I imagine that they would have applauded her for the firm way that she dealt with the interlopers. She is not accustomed to having her rights ignored.

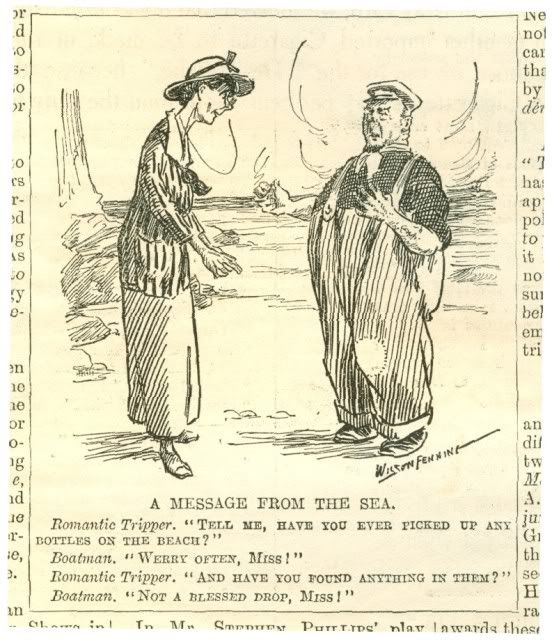

1914: What Didn’t Go Without Saying

Each assumes that the other has the same expectation of the contents of the bottles but they are both wrong.

1914: An Expensive Night Out

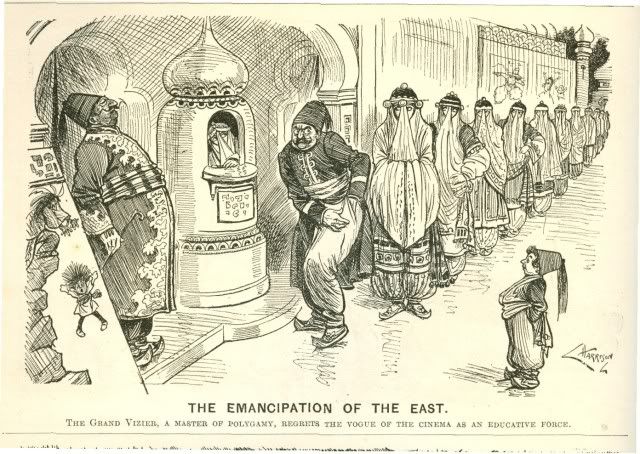

This cartoon bears witness to the popularity of the cinema already in 1914. The artist has had fun with this. He imagines a British man taking his wife to his local cinema. There is commissionaire outside and an urchin looking on. He now sets this scene to the Middle East. The cinema, the writing under the cash desk, the two men and the boy are all shown to belong to his designated milieu. Then instead of a wife we see a long line of wives, similar in size and shape, stretching as far as the eye can see.

His most obvious mistake is that he hasn’t understood how the veil is worn. The writing outside looks nothing like Arabic. It’s a lively joke though I dare say that the artist knew perfectly well that the Grand Vizier would not have taken any of them if he went to the cinema at all. If they were very lucky he might have arranged a private viewing at his palace. The projectionist would obviously have been in a separate room.

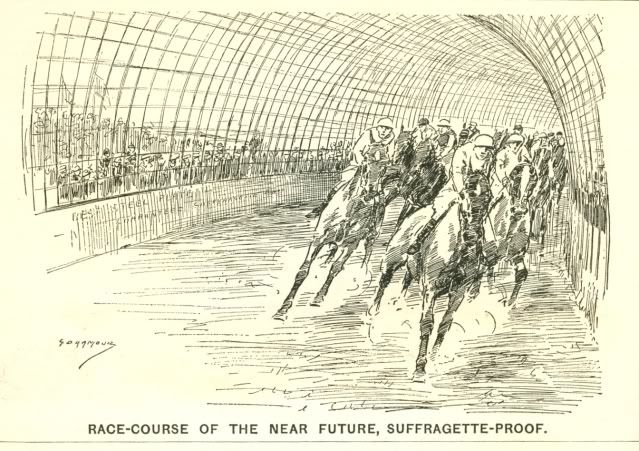

1914: A ‘Joke’ in Doubtful Taste

The title underneath the drawing makes it clear what the artist had in mind. A suffragette, Emily Davison, had stepped right in front of the king’s horse which was running in the 1913 Derby. She died of her injuries.

Public opinion was divided over the issue. Mrs Pankhurst declared the young woman to be a martyr and a military style funeral was organised by the Suffragettes. On the other hand those who opposed the movement were outraged by this act. This cartoon clearly relates to the latter point of view.

That this cartoon appeared at all in Punch seems to us in particularly poor taste. I think that it reflects the severe polarisation of attitudes in the summer of 1914. No one could have predicted the imminent outbreak of war. This was followed by the immediate cessation of all suffragette agitation. Mrs Pankhurst then threw her organisation enthusiastically behind the war effort leading to votes for women over 30 in 1918 and universal adult suffrage in 1928.

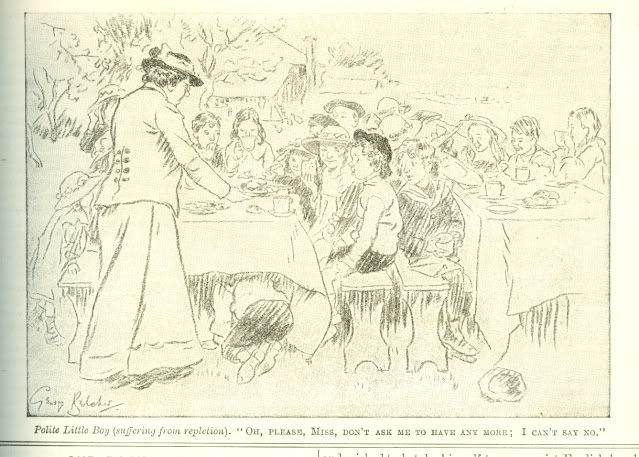

1914: Too Much of a Good Thing

Here is George Belcher already active in 1914. His style is immediately recognisable. Here again he is keeping away from upper middle class people and situations.

These are the children from the village being given a treat while wearing their Sunday best. They are encouraged to eat as much as they like. A likely reason for this event is that it is a reward for regular attendance at Sunday School.

The weather is clearly benign. In the long years of the forthcoming conflict many people looked back with longing to that lengthy warm summer of 1914 when all was still peaceful.

1914: Gerald’s Misdemeanours

Gerald’s mother seems strangely relaxed about her son’s activities. He is, in effect, asking for other offences to be taken into consideration. I suspect that he is bored. The size of just part of the garden gives us an impression of the family’s standing. It may be that the other children in the vicinity are regarded as ‘common’ so he is often left to himself. No doubt when he goes to his public school he will make friends but he will also find that the authorities will be far from relaxed about even minor infringements.

Meanwhile we can see what the well-dressed woman was wearing just before the outbreak of war.

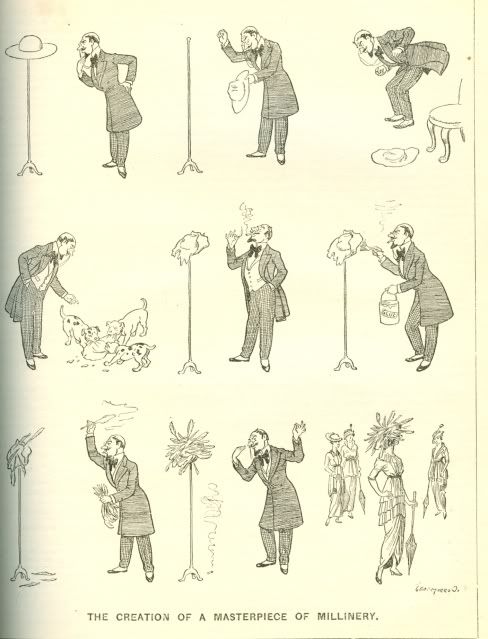

1914: Tricks of the Trade

A satirical look at the art of being different.

The ‘artist’ surely is meant to be French.

![]() what a smart answer. From the boy …

what a smart answer. From the boy …

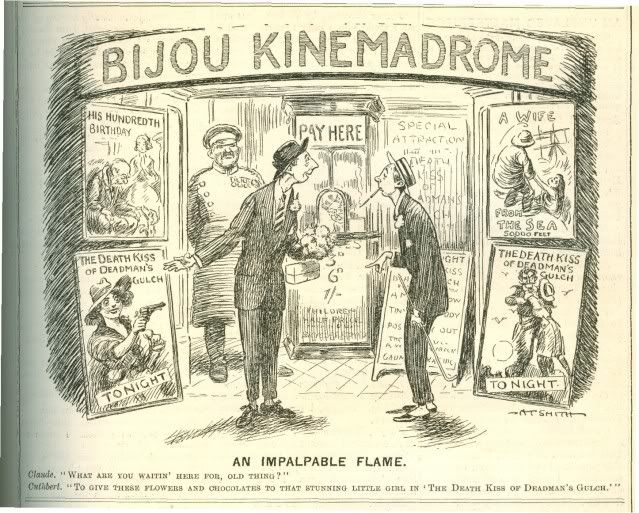

1914: How To Impress an Actress 6,000 Miles Away?

Here is another cartoon about the early days of the cinema. Cuthbert is under the impression that the star of the film is present for the performance. He hasn’t managed to put aside his habits as a Stage Door Johnny when he would lay siege to the object of his affections at a theatre or music hall. No doubt Claude will put him right.

The artist has chosen to portray both the young men as effete weaklings. In the early days of the war recruiting officers would turn away volunteers with this kind of physique. Later on with conscription breathing seemed to be the only qualification.

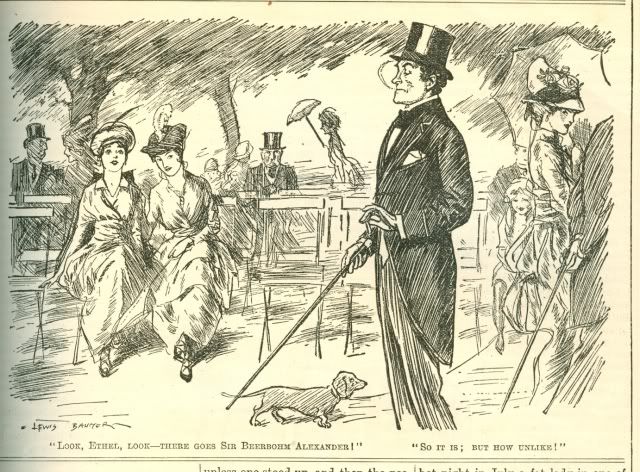

1914: On Seeing a Celebrity in the Flesh

Ethel and her friend will have studied the magazines containing pictures of prominent people in the news who would nowadays called celebrities. She has mixed up the names of Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree and George Alexander. Both are highly respected actor managers.

The two young women are witnessing the same effect that people have today when they actually meet someone previously only seen on television.

‘Sir Beerbohm’ looks entirely convinced of his pre-eminence.

1914: “Equality”?

This cartoon seeks to take a light-hearted look at the women’s movement in 1914. It reminds us that women were not just demanding the vote. There was a strongly expressed desire for women to be able to earn a decent living in their own right. Medicine and the law were obvious targets. The church was not immune for these demands. All were strenuously resisted by the male establishment.

Here the cartoonist looks at another all male institution: prize fighting. His drawing takes a typical scene from this activity and replaces all the people present with female equivalents. So we see women contestants, the seconds, the audience and (splendidly) the referee. The seconds are supporting their champions by typically female methods.

I doubt that the artist wants us to think that they have really traded heavy punches with each other although boxing gloves are present. I suppose that the matronly referee is counting out the champion on the right while her seconds are trying to revive with the use of a fan and some perfume. The woman on the left is already preening herself ready to be declared the champion.

I can’t imagine that there was any demand at that time for women to be allowed to batter each other senseless for public display though I did notice that women’s boxing had become an official event in the 2012 Olympic Games.

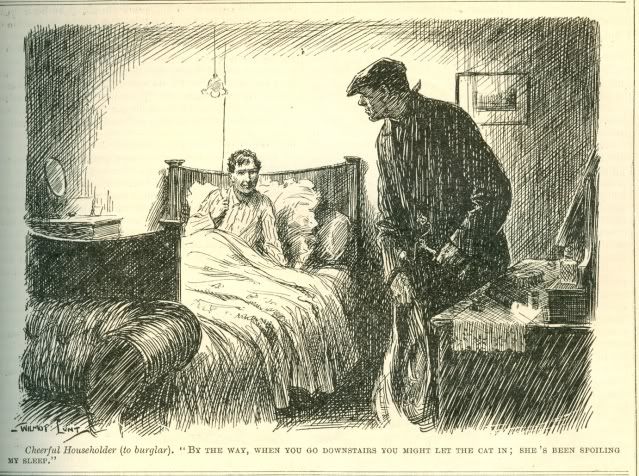

1914: Making Light of It

I suppose the joke is simply that the householder appears to be neither outraged nor frightened though in reality he might well be both. Here he is shown to be calmly accepting the situation and making light of it.

It would have been unwise to take on this burglar.

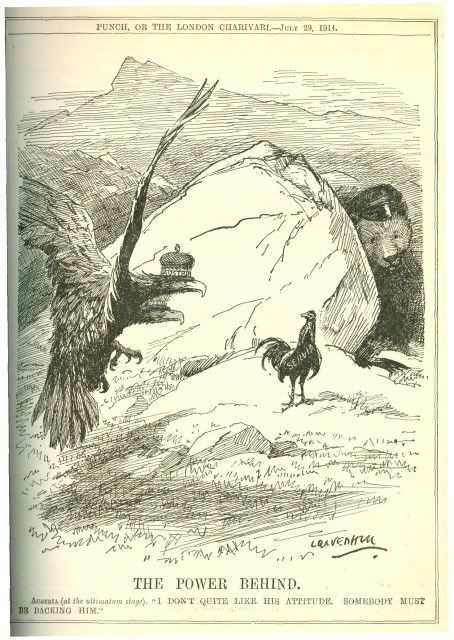

1914: On The Threshold of Catastrophe

18 June 1914: Assassination of the Austrian Archduke

3 August 1914: Britain declares war on Germany

This cartoon appeared on 29 July – a mere five days before Britain entered the war though it might have actually been drawn a week earlier. It is the first reference in Punch to this situation in the Balkans. With hindsight it seems remarkably unaware of the perils to come. The cartoonist correctly reflected the view of his fellow citizens that this was a mere continental dispute in which Britain had no interest.

The eagle is double headed because it represents the dual monarchy of both Austria and Hungary. The intransigent cockerel represents the much smaller kingdom of Serbia. Behind the boulder lurks the Tsarist Russian bear. As anticipated in this cartoon, as soon as Austria-Hungary attacked Serbia, Russia declared war on the Dual Monarchy in defence of its Slav ally. As soon as Austria was attacked Germany was treaty bound to declare war on Russia. France was then obliged by treaty to declare war on Germany. For a short time Britain’s position remained in doubt but as soon as Germany attacked Belgium, Britain was bound by treaty to attack Germany.

The British Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, probably did say the lamps are going out all over Europe, we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime. Some would say that they never really have been relit.

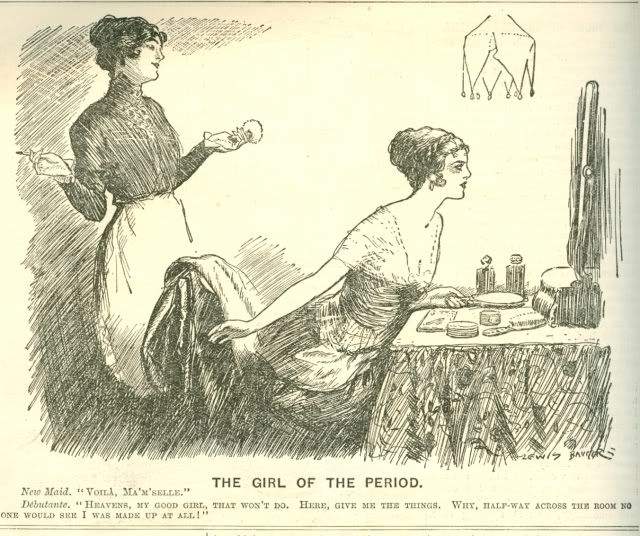

1914: Which One of Them is Right?

Unperturbed by the goings-on in the Balkans the question here is whether the new maid or the debutante is in the right. Although I am a complete ignoramus on the subject I would say that the consensus today is that the maid is right on the grounds that less is more.

I suspect that in (just) pre-war 1914 people would have agreed with the deb.

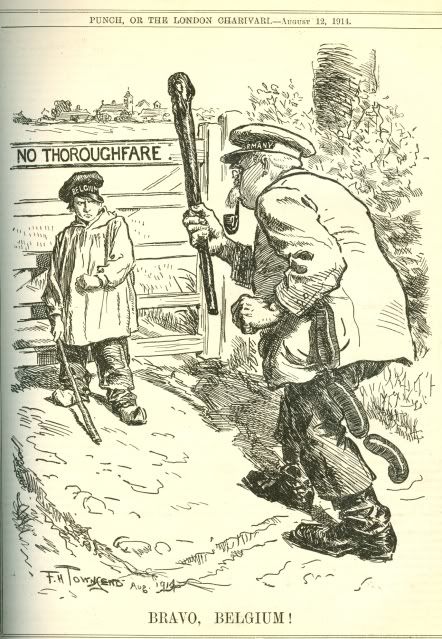

1914: The Scrap of Paper

This cartoon shows exactly how Britain became a willing participant in the war. The understanding with France reached in the previous decade might or might not have persuaded the Asquith government to join in the war. That issue was never put to the test because of the German demand that her troops be allowed to pass through Belgium in order to attack Northern France. Obviously this would be a violation of Belgian sovereignty but the Germans expected it nonetheless because of their overwhelming superiority.

When Belgium refused the Germans simply invaded their small neighbour. As this cartoon shows there was widespread British admiration for ‘plucky little Belgium.’ Indeed, there existed a British treaty to guarantee Belgian independence. The official British response was now inevitable and almost universally popular. A German diplomat expressed dismay that Britain would do this for a mere ‘scrap of paper.’

In this way right from the start the British public came to see the war not just a matter of power politics and alliances but of morality. The German war machine was to provide additional reasons to buttress that sense of moral superiority for the allied cause.

From now on the war would continue to dominate the pages of Punch as it was to do in all aspects of the nation’s life.

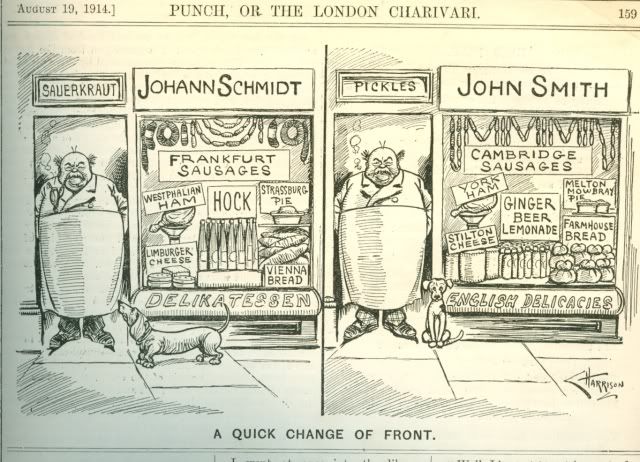

1914: Early Example of Anti-German Sentiment

Before I looked at these cartoons in detail I had expected anti German feelings to develop in response to major battles which caused enormous numbers of British casualties. However the date of this cartoon demonstrates that this feeling had developed almost overnight.

Herr Schmidt had many years earlier settled in Britain in order to make an honest living providing German wares which had been very popular. Had he really been a spy he would not have identified himself so strongly with the country of his origin. The cartoonist seems to condemn him for trying to anglicise his name, his wares and even his dog. Thus he was being condemned not for what he had done but for what he was.

This early in the war the popular mood seems to have been a case of mass hysteria which was being egged on by the popular press such as Lord Northcliffe’s Daily Mail. I understand that there was an equally irrational anti British mood in Germany.

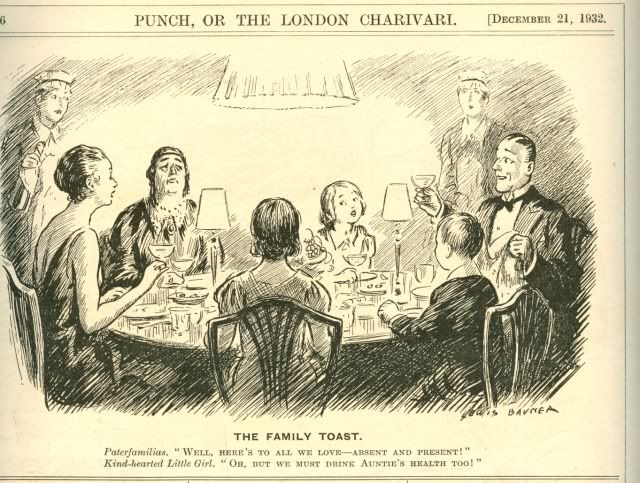

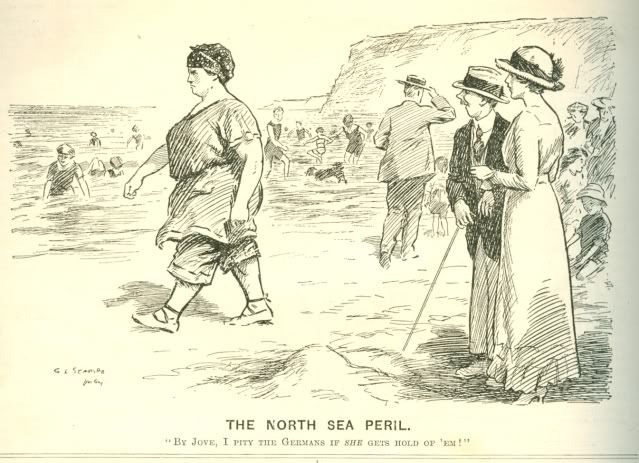

1914: Thinking About the War at the Seaside

The war had started during the peak holiday season. This cartoon shows how quickly the war was beginning to permeate the daily lives of the entire population.

By contrast the letters of Jane Austen more than a century earlier contain very few references to the long wars with France, first against the revolutionaries and then against Napoleon. By 1914 far more people could read and now there were newspapers available with ‘popular’ appeal. Jane knew about the war, of course, but apart from concern for her two brothers in the Navy she didn’t feel personally concerned. She would not have considered knitting socks for soldiers!

We are also treated to a view of how people were dressed when enjoying their seaside holiday.

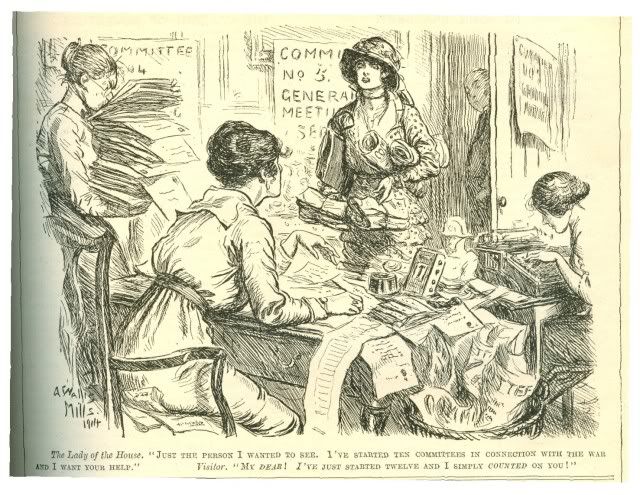

1914: Too Many Chiefs and Not Enough Indians

This cartoon illustrates how bossy upper middle class women became hyperactive right from the start of the war. Whereas previously their energies could only go into church bazaars and garden fetes now suddenly they could spread their wings and organise far and wide to their hearts content.

This scene depicts a limit to the ambitions of these busybodies. The lady of the house has two helpers, who do the actual work. Each is either directly employed by her or is in some was beholden to her. She wrongly assumes that her visitor, who is as well heeled as she is, can be drafted in to do the actual work. The trouble is that her visitor had come looking for another ‘mere’ committee member. Each is equally convinced that it is she who should be directing ‘her’ committees.

On matters of attire it seems that the visitor has outclassed the lady of the house.