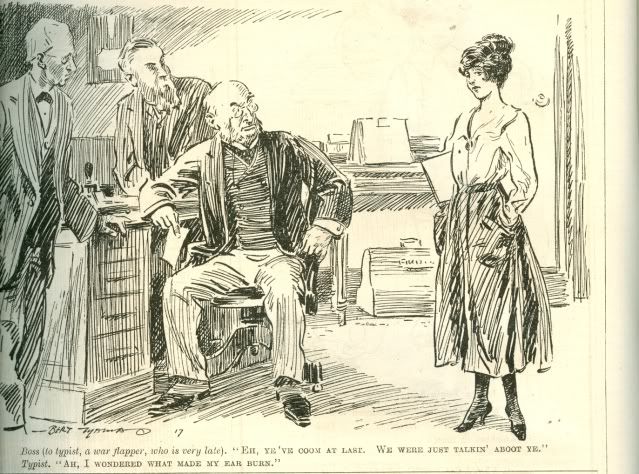

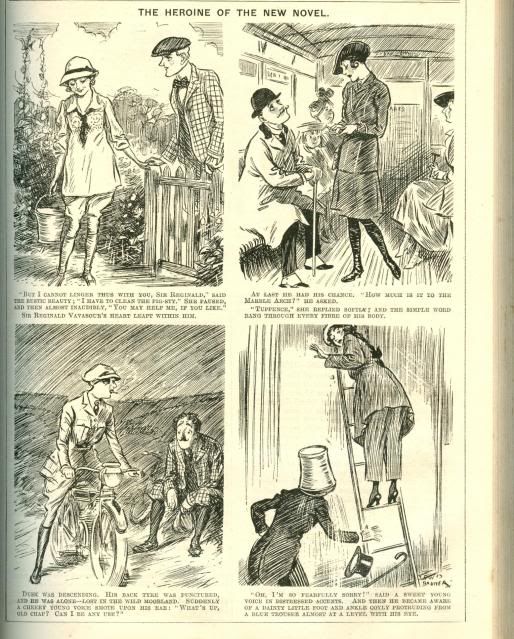

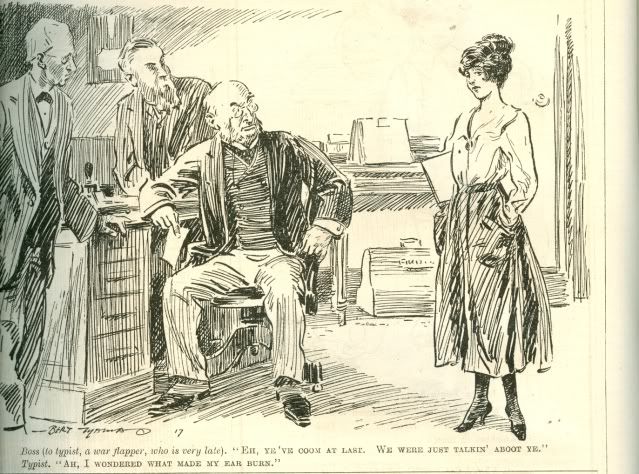

1917: An Addition to the Vocabulary

According to Wikipedia:

Flappers were a “new breed” of young Western women in the 1920s who wore short skirts, bobbed their hair, listened to jazz, and flaunted their disdain for what was then considered acceptable behaviour.

Here we see evidence that the term has an earlier origin. This particular flapper is not afraid of dismissal, and in the worst case she could easily find a job elsewhere. The old buffers, much to their regret, have to put up with her.

After the war things quickly reverted to the old order although when in 1928 women were permitted to vote at the age of 21 (like the men) pollsters referred to the ‘flapper vote.’

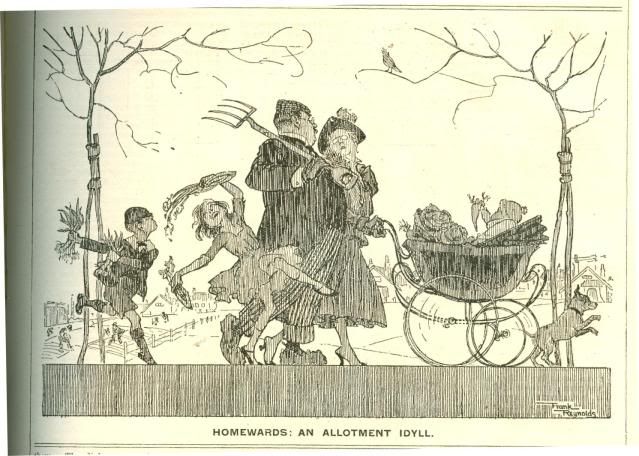

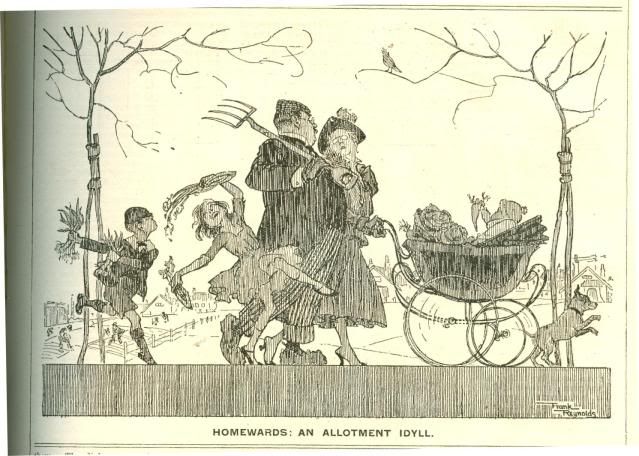

1917: More About Food Shortage

Obviously Punch was being read by well-heeled members of society. We get ample indication that they too were conscious of food shortage due to the U-boat blockade of merchant shipping coming to the UK. Rationing had been introduced to ensure that everyone got the same. As in the Second World War this meant that people at the bottom were better fed than before the war. Prices were also controlled.

The drawing itself is a deliberate fantasy suggesting that tending your patch was an entirely pleasurable experience. Clearly everyone knew that this was not the case.

1917: The Lower Orders Are Revolting

The background to this cartoon concerns the army’s insatiable demand for munitions and other instruments of war. In particular the lack of enough shells was a constant problem for the Allied High Command.

The cigar smoking factory worker in this drawing was able to increase his disposable income substantially by working enormous amounts of overtime. The readers of Punch were not exactly envious but they were uneasy about what was happening to what they considered to be the natural order of things. The implication here surely is that manual workers had no right to be purchasing a piano – this was the natural preserve of their ‘betters’.

After the war things very quickly returned to the previous state of things.

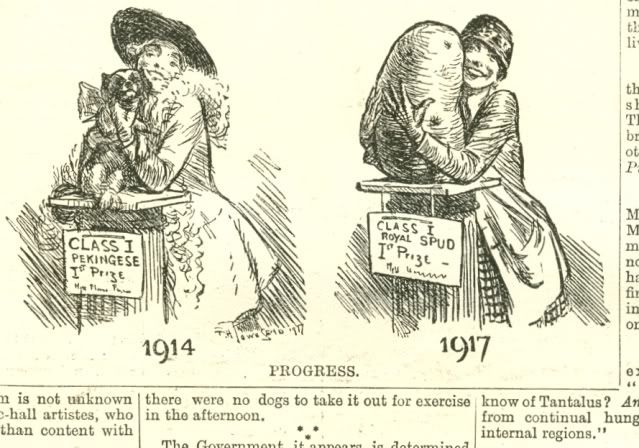

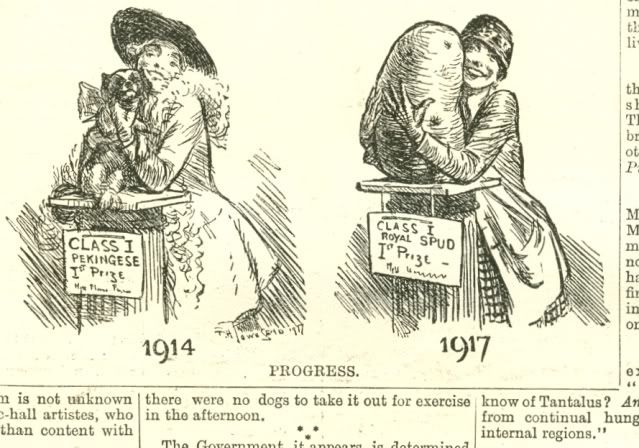

1917: The New Priorities

It looks like a marrow although it is labelled as a spud. Whatever it is she now prizes it more than she had previously prized her dog.

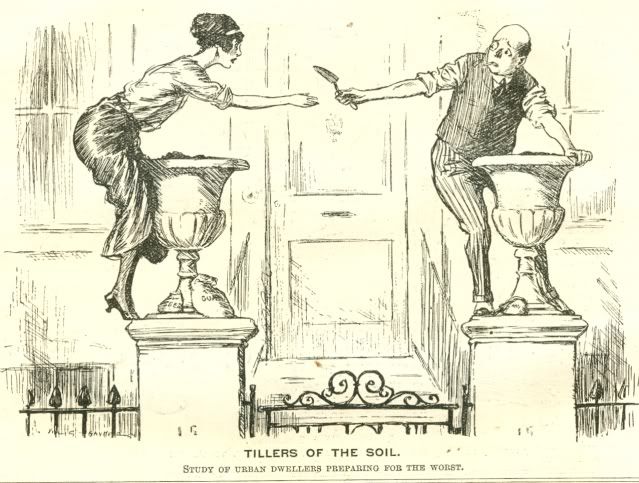

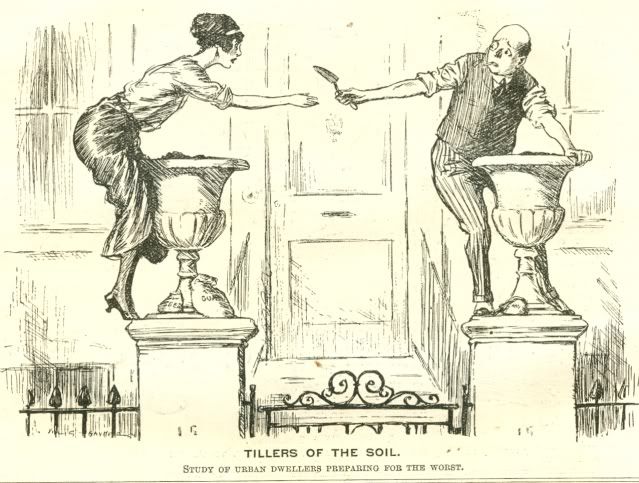

1917: Food Once Again

This is obviously a somewhat fanciful suggestion. They won’t be harvesting much here. We do see that these urban ‘food growers’ are well heeled indeed. Because of the war they couldn’t just order a hamper from Fortnum & Mason.

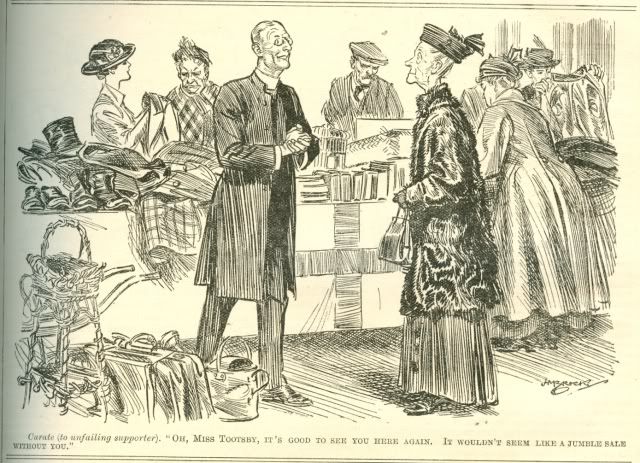

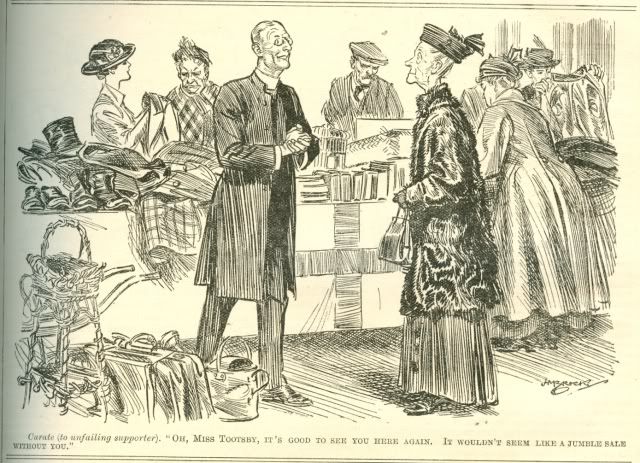

1917: Something That Could Have Been Better Expressed

The jumble sale has been lovingly represented. Two less well off members of the congregation are looking critically at what is on offer. The lady on the left surely is a volunteer who is praising the item that she is holding up to a sceptical parishioner. Miss Tootsby is a long-standing supporter of the church.

The curate looks much too grand (and mature in years) considering his lowly position in the hierarchy. He would look much more convincing if he appeared in a different cartoon and described as a bishop.

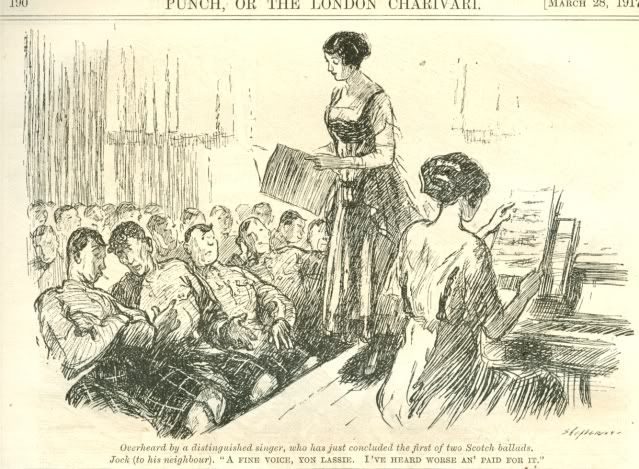

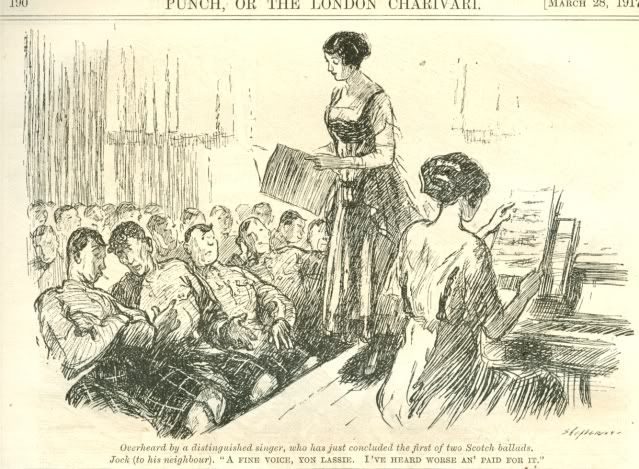

1917: Faint Praise

Jock is unaware of the distinguished status of the ‘lassie’ who is entertaining the troops in order to show her support of the war effort. She probably appreciates his praise since he doesn’t know better.

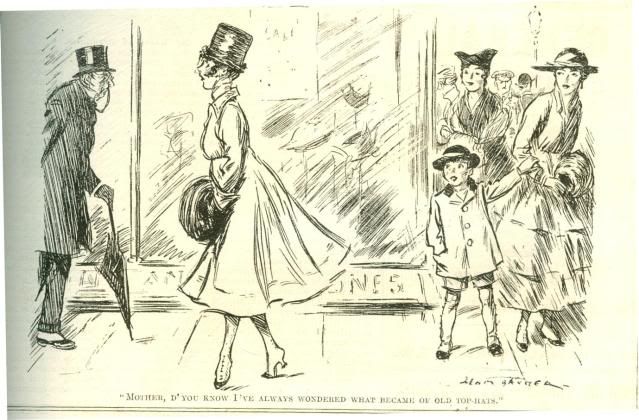

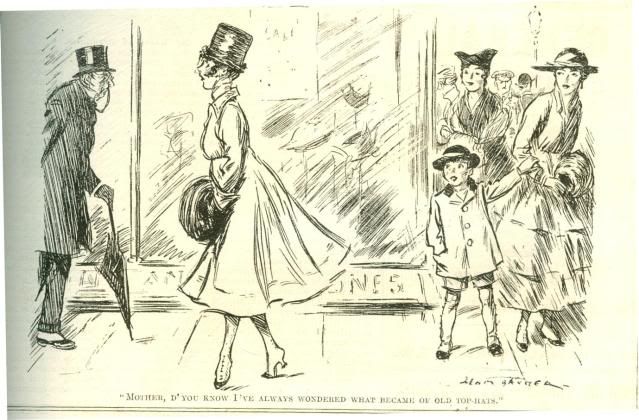

1917: A Fashion Note

Recycling Ahead of it Time?

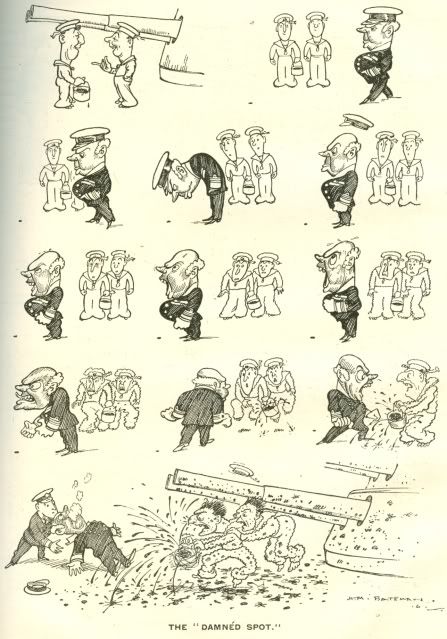

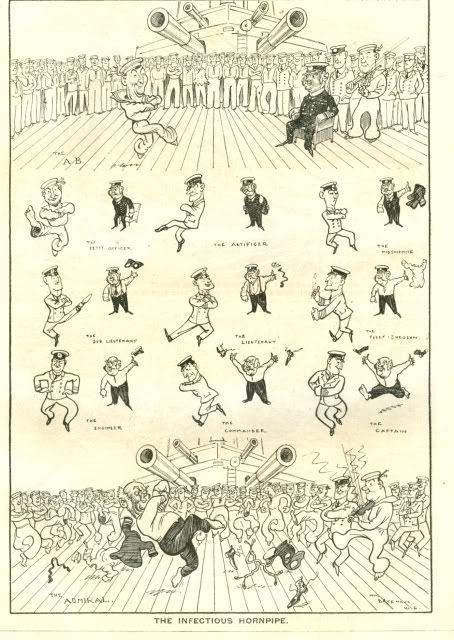

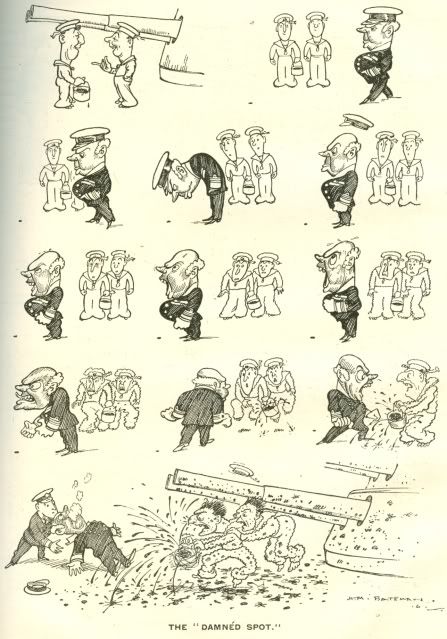

1917: H M Bateman in the Navy

The unmistakable hand of Bateman is at work here. Not so much ‘The Man Who …’ as ‘The Admiral Who Lost His Temper.’

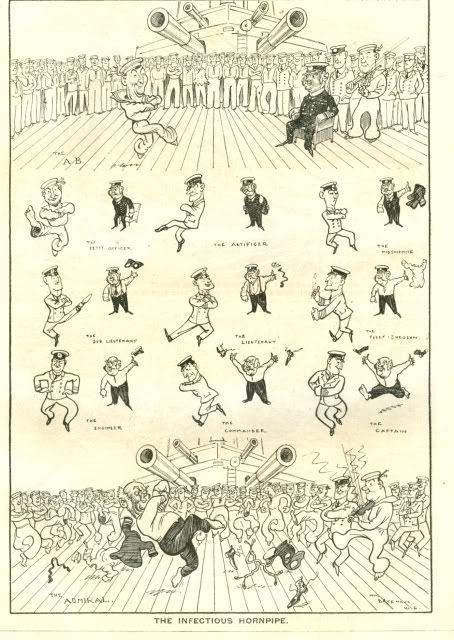

1917: Life at Sea

Bateman’s scene surely is set on a battleship and everyone eventually lets his hair down. It presents a kindly, indeed, nostalgic view of naval tradition.

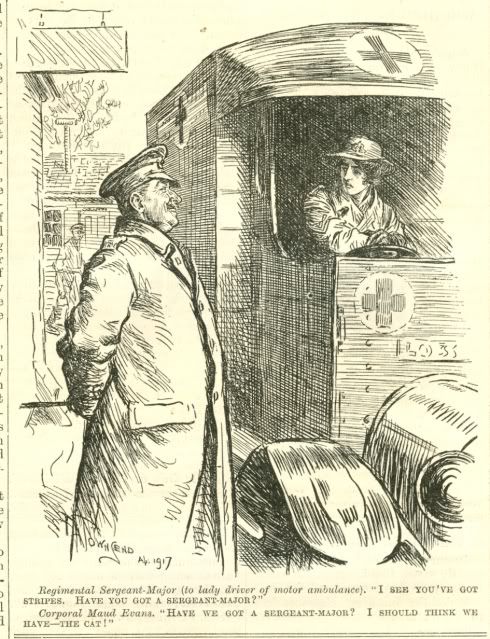

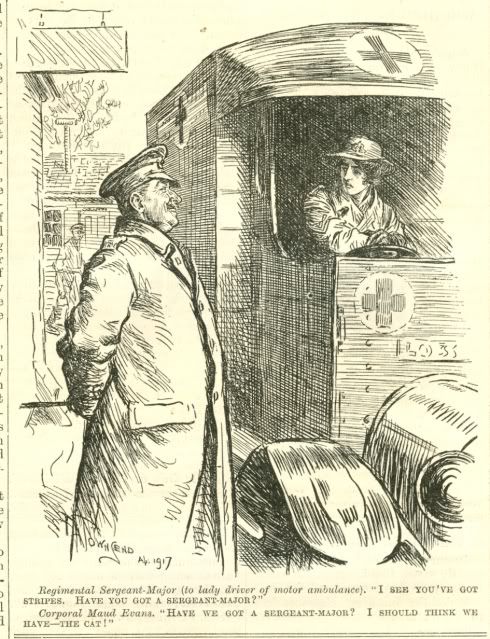

1917: Ladies in Uniform

The RSM is intrigued by the fact that the women in uniform also have the same ranks as the men in the army. By the look of him he seems to considering amorous possibilities and wonders whether his ‘opposite number’ would be a suitable conquest. Chances are that he would not find her to his taste and that he might be more interested in the ambulance driver herself.

The practice of calling a woman ‘a cat’ as a term of abuse seems quite anaemic to us today. I can only recall one instance of this use and that was in Galsworthy’s Forsyte Saga. Here is the extract (found thanks to Google):

He had flushed the peculiar flush which always centred between his eyes; lifting his hand, and, as it were, selecting a finger, he bit a nail delicately; then, drawling it out between set lips, he said: “Mrs. MacAnder is a cat!”

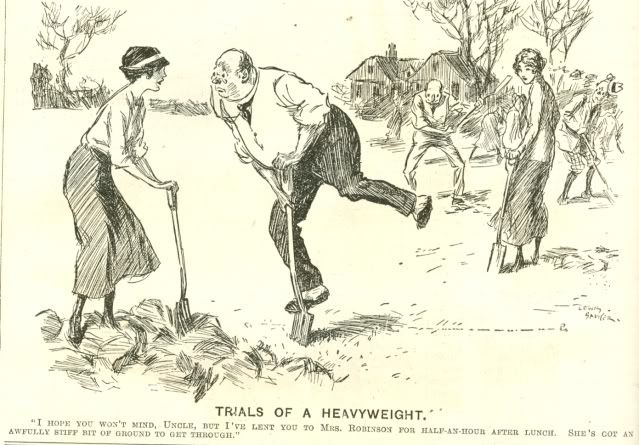

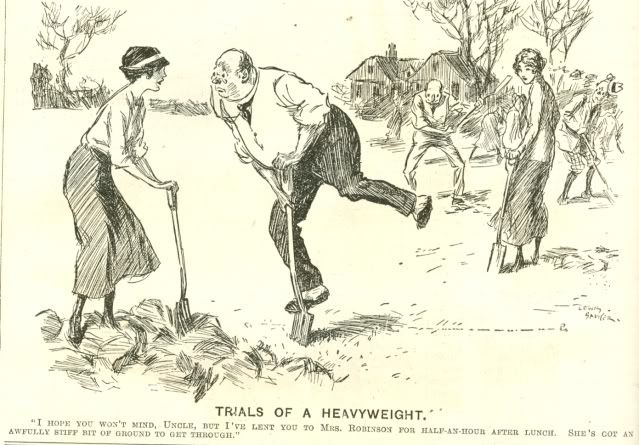

1917: Food Shortage Yet Again

The interesting thing here is that the toffs are now doing the hard manual work. The sheer number of food jokes is surely testimony to a severe shortage. The young woman’s uncle looks far from pleased at the though of having to do more heavy digging for Mrs Robinson. She looks as though she is playing the ‘I’m just a helpless female’ role. Uncle’s spats look particularly inappropriate for the task in hand.

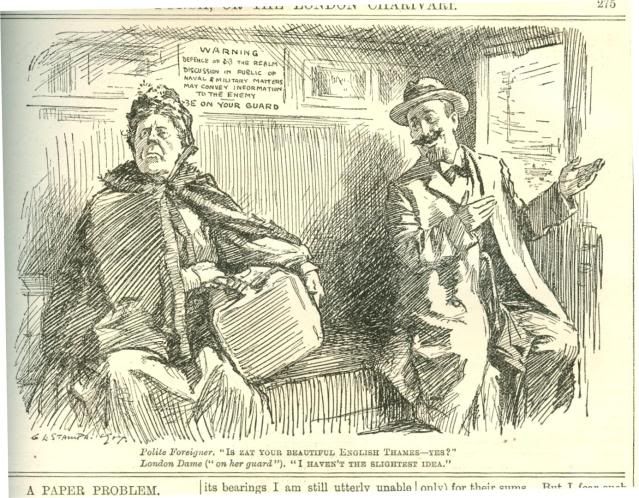

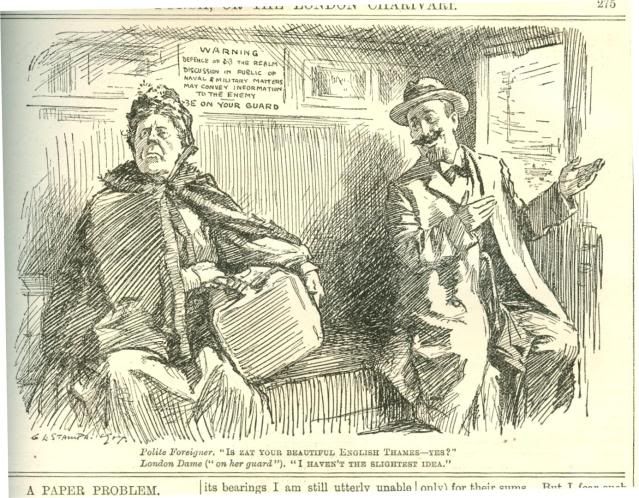

1917: Spy Mania Again

Early in the war we saw quite a smattering of cartoons about spies. Here is another one though in this case it is treated as a joke.

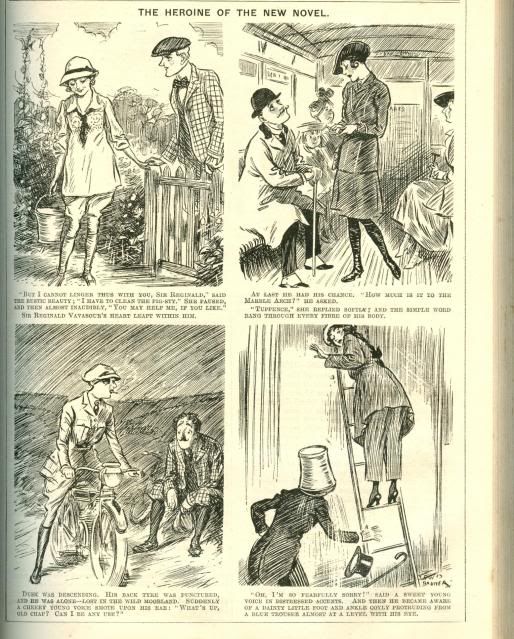

1917: Women Doing a Man’s Job

I see that Mills and Boon was founded in 1908. It may therefore be that this cartoon is inspired by that actual firm. The cartoonist is having a lot of fun with the possibilities for romantic fiction caused by women taking on men’s jobs during the war. This is a well thought out and well executed joke.

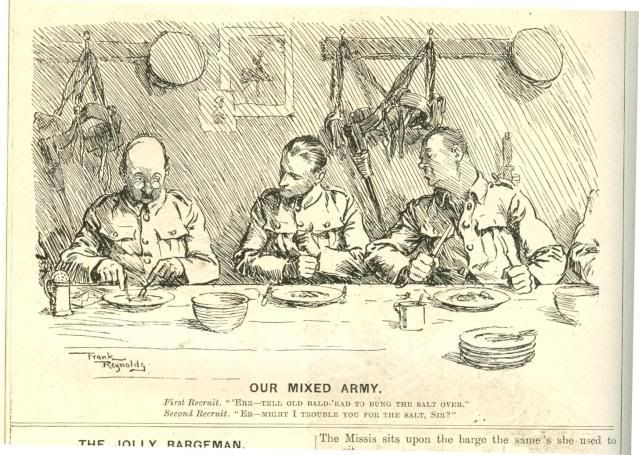

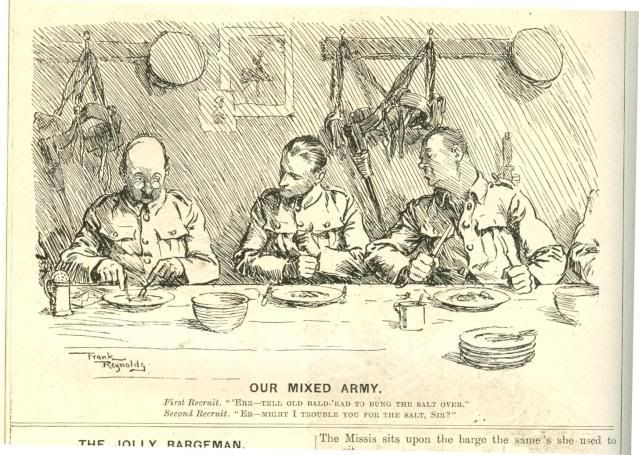

1917: The Man in the Middle

In this scene all the men are recruits who have been thrown together regardless of their backgrounds. The man in the middle has understood the request of the man on the right. He chooses to convey it in a manner more suited to his own background. It is not clear that the man on the left will find this form of words preferable to the original question. On balance I would think that he does when we compare his table manners to those of the original questioner.

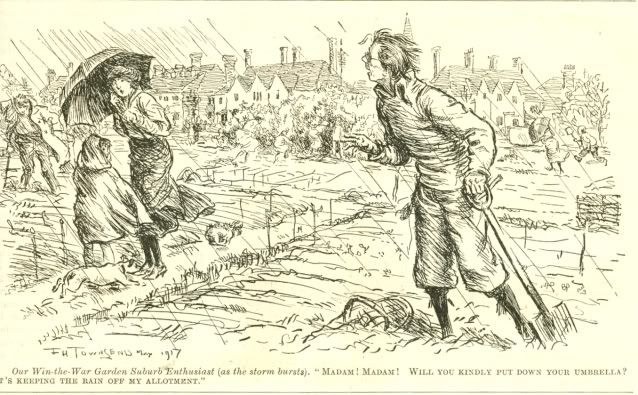

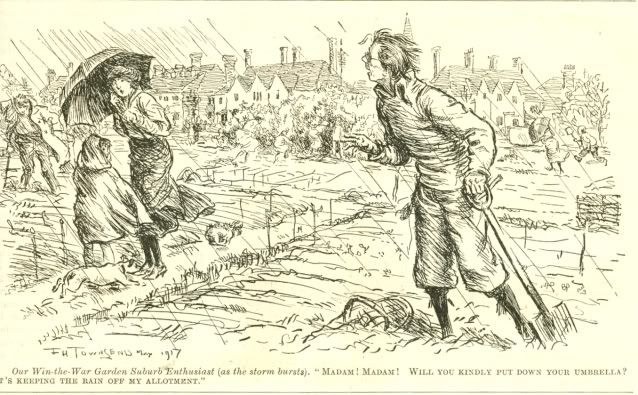

1917: A Dose of Reality

Unlike an earlier cartoon in which a family is dancing home from their allotment we see here a much more realistic picture of food cultivation.

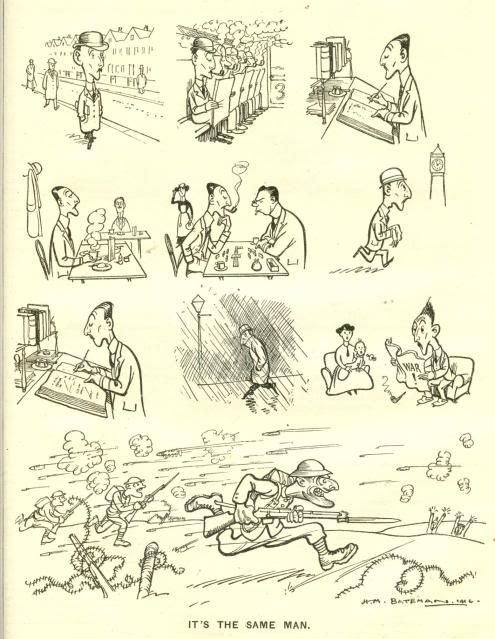

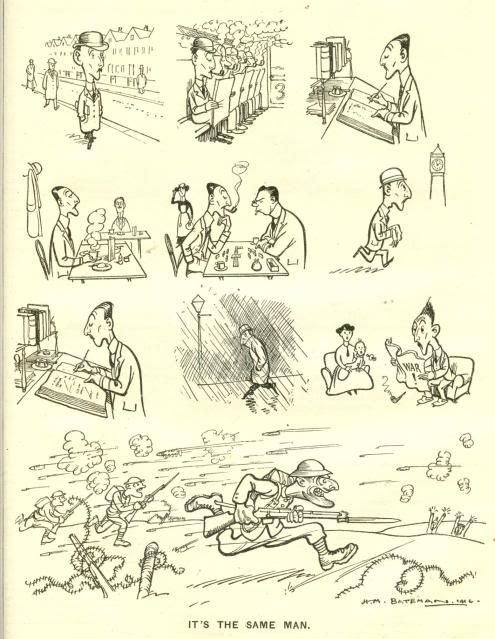

1917: By Jingo

HM Bateman is here in a gung-ho mood. This sits oddly with the known mood of the nation by 1917. The fighting is not realistically portrayed. There are no trenches, there are only wisps of barbed wire and the bullets are whizzing harmlessly past the brave (indeed reckless) Tommies while Fritz is pathetically eager to surrender. This is not reality as experienced by those doing the actual fighting.

The signature at the foot of the drawing gives a date of 1916. I would have guessed early 1916. In fact, I think the sentiment belongs to an even earlier period. I suppose that the drawing had been lying around and someone decided to use it at this juncture. Perhaps this was in the hope of recapturing some of that early enthusiasm.

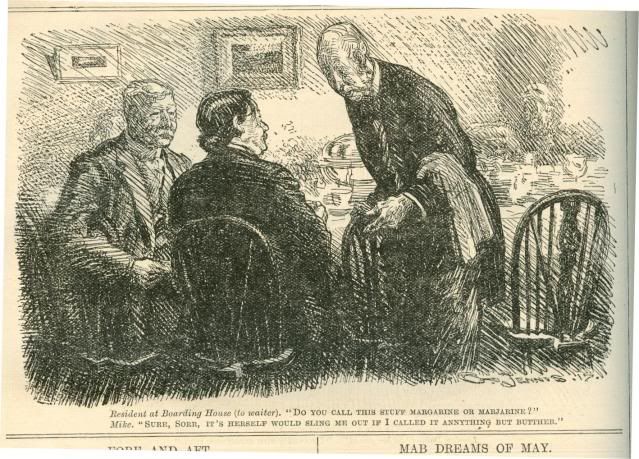

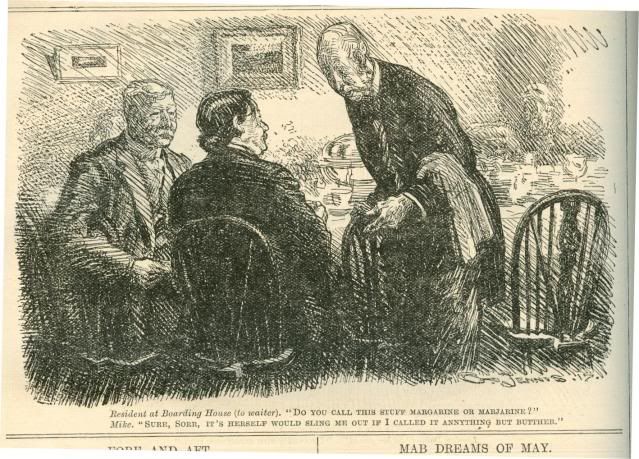

1917: Food Again

The Irish waiter has answered the question in his own discreet way. I suspect that in 1917 it was very easy to detect the difference and it would have been pointless to conduct an ‘I can’t tell the difference’ campaign.

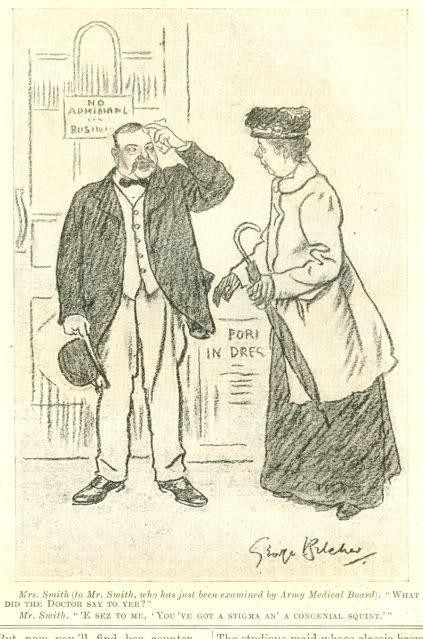

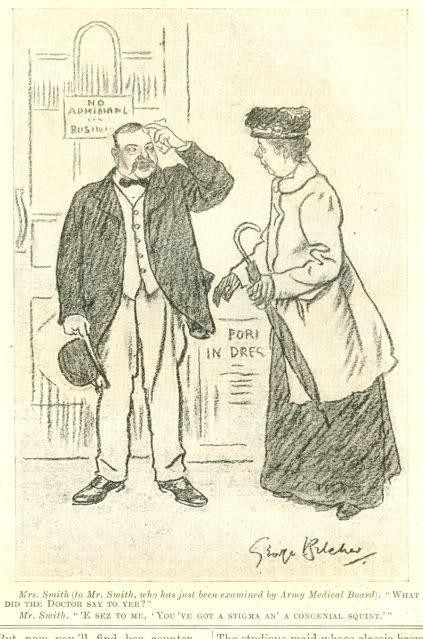

1917: Malapropism and the War

We are witnessing here the effect of the high rate of casualties in the war. Quite apart from his astigmatism in view of his age Mr Smith would in 1914 have been rejected even if he had volunteered. By 1917 it was no longer possible to be so choosy.

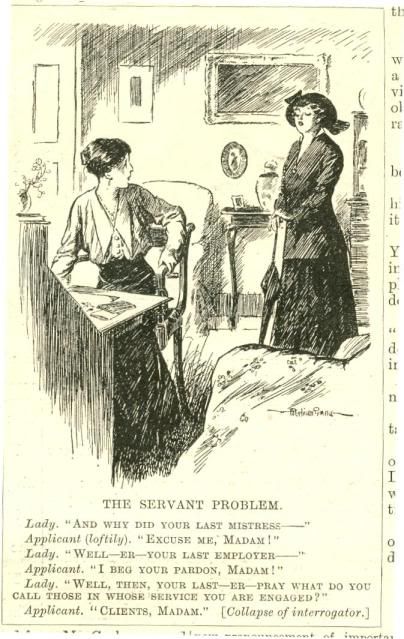

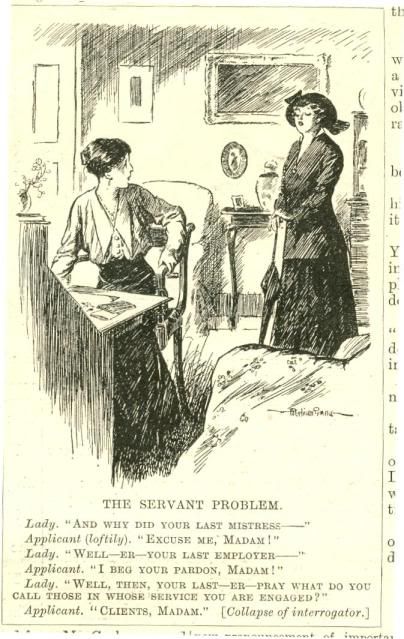

1917: A Topsy Turvey World

Like many of the readers of Punch the lady of the house is grappling with the servant problem. I suspect that the applicant’s lofty manner is somewhat exaggerated in spite of the many alternative employment opportunities that existed in 1917.