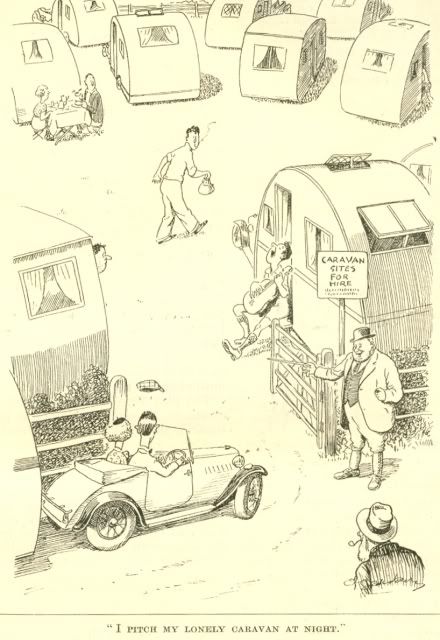

1935: Getting Away From the Crowds

There obviously was a fashion for taking caravan holidays. As the cartoon shows us they seem to have been anything but solitary.

1935: Getting Away From the Crowds

There obviously was a fashion for taking caravan holidays. As the cartoon shows us they seem to have been anything but solitary.

1935: The Professor’s Memory

A university is an unusual setting for George Belcher’s cartoons. Using a modern analogy the professor thinks that his memory is like the fixed disk on a computer. If it is full you have delete stuff in order to store something else. I have the distinct impression that human memory is not like that at all. I also think that even in 1935 his opposite number in the Psychology Department could have told him this.

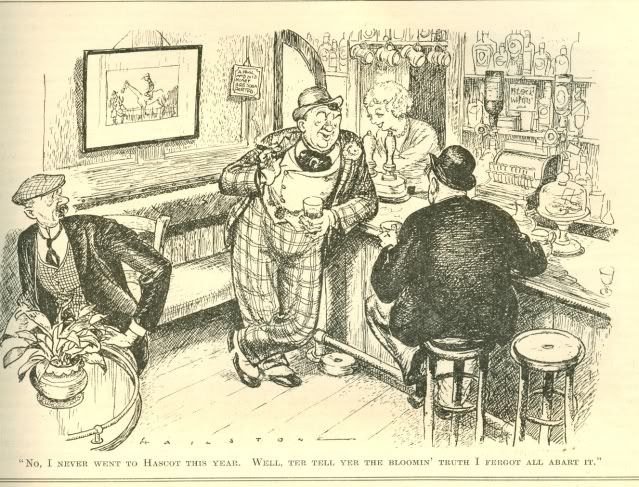

1935: Taking the Mickey

I am wondering if the speaker in the ‘loud’ clothing is a bookmaker. The barmaid finds his banter amusing. He, too, is wearing spats.

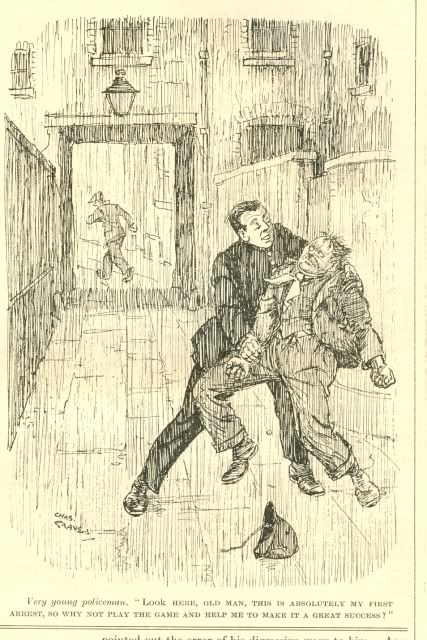

1935: Playing the Game

The criminal clearly didn’t go to the same school as the keen as mustard young copper. What’s the betting that he will give the younger man the slip?

I have now finished showing my 1935 cartoons. We now will switch our focus onto 1917. The war was in its third year and that initial enthusiasm of 1914 had largely evaporated. Instead there was the grim realisation that it was going to be a long, hard slog. The opportunities for humour were fewer but they did exist and the Punch artists did their best under the circumstances. Comments on the military tended to avoid the actual conflict but instead centred on the vagaries of army life. The ‘civilian’ cartoons were almost exclusively devoted to the effects of the war on the ‘home front.’ Two ever-popular themes concerned the effects of food rationing and the way women were now assuming roles previously confined to men.

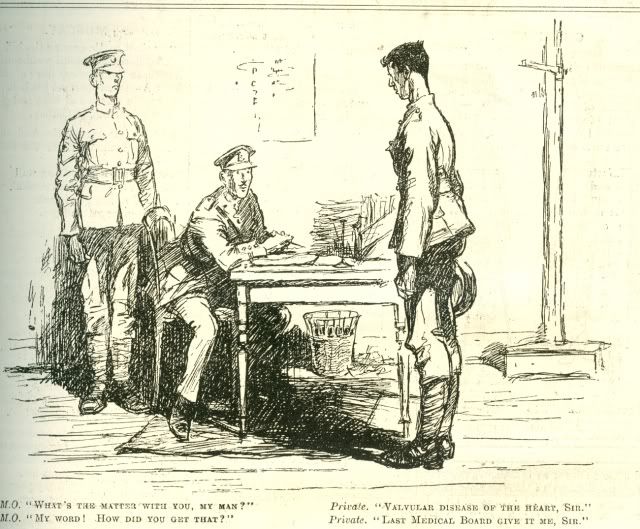

1917: The MO is Confounded

Without the Internet doctors were unaccustomed to their patients having any medical knowledge at all. Here the Private has simply memorised the words but the Medical Officer (MO) is nevertheless impressed. In answer to the next question the Private reveals the extent of his medical knowledge.

1917: Market Forces

The critical importance of munitions (especially shells) had been realised well before 1917. Already in 1915 Lloyd George became the Minister for Munitions, a government department having been hastily created for him. The German industries based in the Ruhr were highly efficient. Manpower was critically important and wages rose as a result of incessant demand. This cartoon is a good example of how this affected age-old levels of remuneration. The readers of Punch were not happy with this trend.

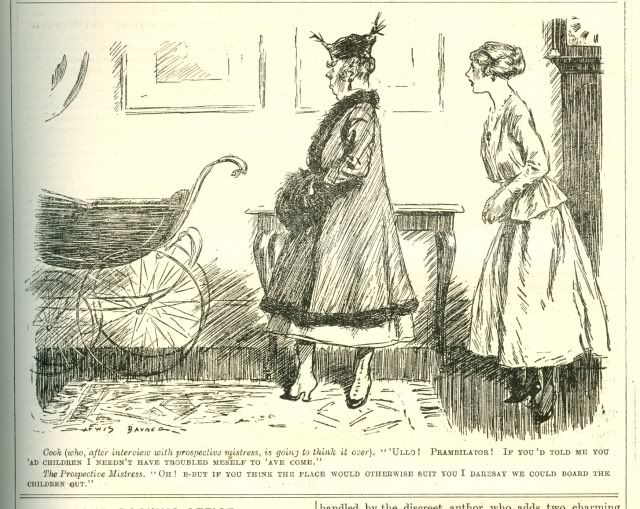

1917: The Servant Problem in Wartime

This cartoon reflects a social issue during World War One. By 1917 many women were undertaking work previously done by men. As a result the demand for various kinds of household servants exceeded the supply.

The cartoon is clearly not intended to be taken seriously but the prospective employer’s anxiety to employ a cook is genuine enough.

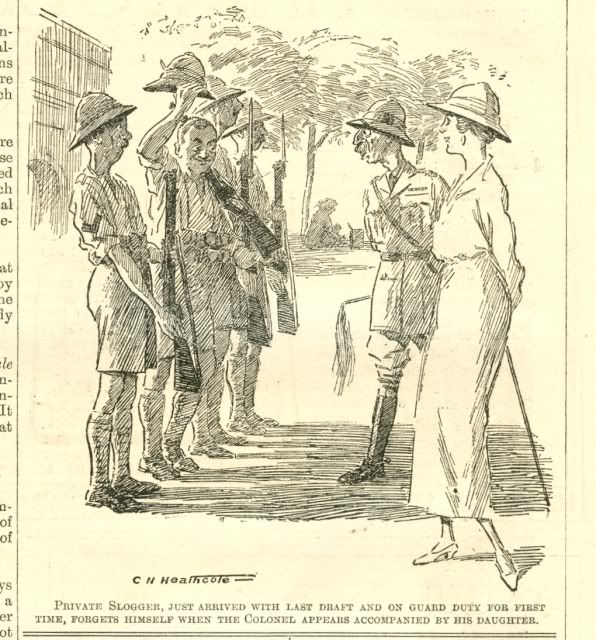

1917: An Outpost of the Empire

While the war was being ferociously fought in France it was still considered necessary to provide soldiers for the garrisons in the various and many parts of the British Empire. However, when we look at the soldiers here on guard duty and, of course, their colonel we see that these men are far from being A1 material.

Slogger is obviously not a professional but a war service soldier. In other circumstances he would have been the colonel’s daughter’s social equal. She, too, is well aware of this fact.

The sight of all these pith helmets reminds me that I was fortunately not forced to wear this ridiculous piece of headgear in Singapore in 1954/5. Right up till World War Two these were considered essential to the health of any European in the tropics. During that war they were found to be quite unnecessary. Our uniform hats were just ordinary army berets and when going out off duty in civvies we didn’t find it necessary to wear anything at all to cover our heads.

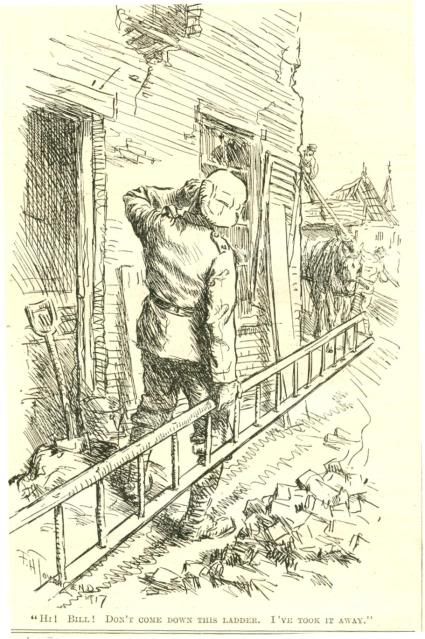

1917: An Old Chestnut Appearing in Uniform

Ladders always provided opportunities for humour in the pages of Punch. The only thing that is different here is that the speaker is in the army.

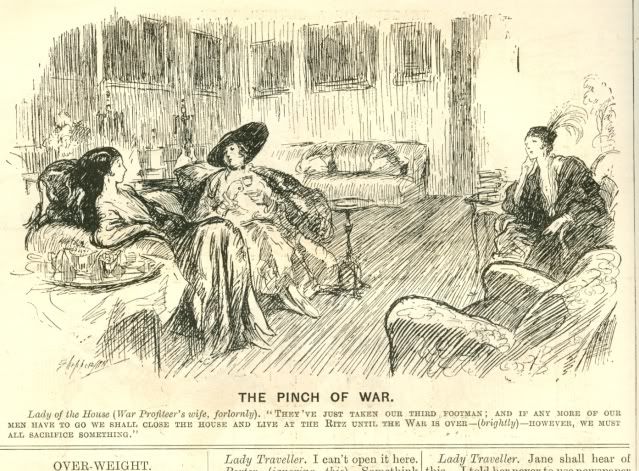

1917: No Sympathy for Lady Muck

It isn’t hard to spot who is the war profiteer’s wife. She’s the well-upholstered one with cup in hand. The war machine needed plenty of supplies. These mainly included munitions but there were plenty of other juicy contracts to be had for supplying the forces with uniforms and all their other bits and pieces.

The term ‘war profiteer’ implied that those who ran the supplying companies were unpatriotically making a profit instead (presumably) of doing it for nothing. Behind the criticisms was the fact that people one had previously despised for being ‘in trade’ were now living more lavishly that the pre-war upper middle classes who did not like to be outshone. These digs at the profiteers were to be repeated again and again in Punch during the 20s and 30s.

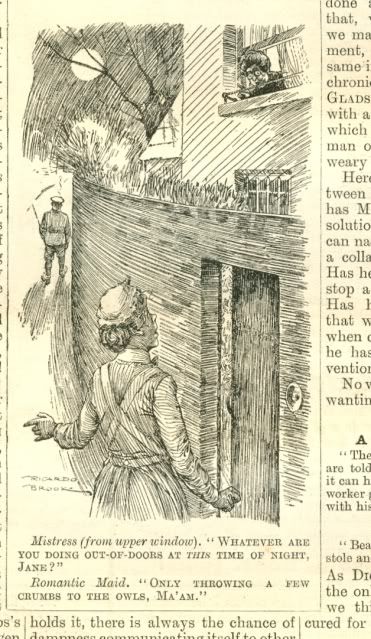

1917: A Time of Opportunity

Jane, like many others, was taking advantage of opportunities which the war brought in its wake. Although, no doubt, the terms of her employment stipulated ‘no followers’ she need not worry about losing her situation. There were so many more chances for employment (as well as other things).

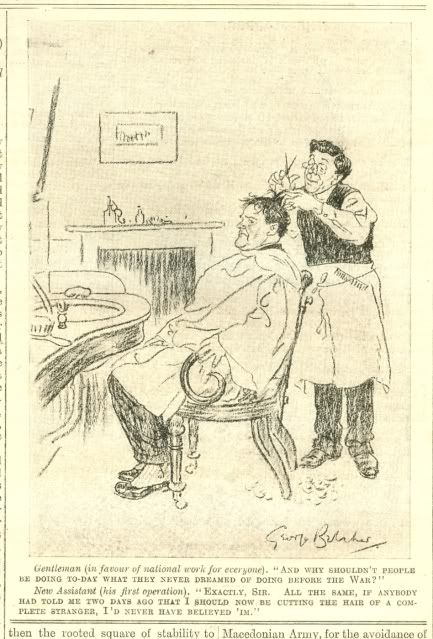

1917: Too Close to Home

The customer had not anticipated that his pet theory was being applied to his present situation. Wouldn’t the cartoon have had more point if the tyro barber was about to use the cut-throat razor?

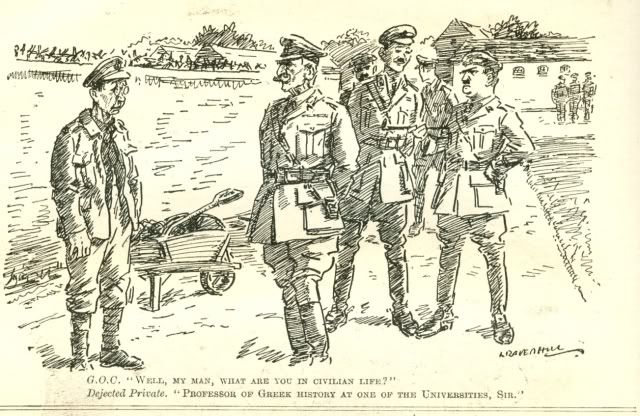

1917: A Citizen Army

What is the point of this ‘joke’?

I note that the General and his entourage are all fit and well turned out whereas the Professor is neither of those things. The ‘Prof’ is now in charge of a wheelbarrow and a shovel.

From a military point of view this Private is little more than useless. I wonder whether by 1917 with the war going far from well the readers of Punch could be expected to endorse this opinion.

1917: Scraping the Bottom of the Barrel

By now recruitment centres were no longer besieged by eager young men determined to get into the army before it was too late. This cartoon honestly reflects the new reality. The corpulent Recruiting Sergeant clearly enjoys regular meals and no doubt plenty of liquid refreshment. The recruit is shabby, unfit and not too bright either. Yet the needs of the military now meant that even this feeble specimen could not be rejected.

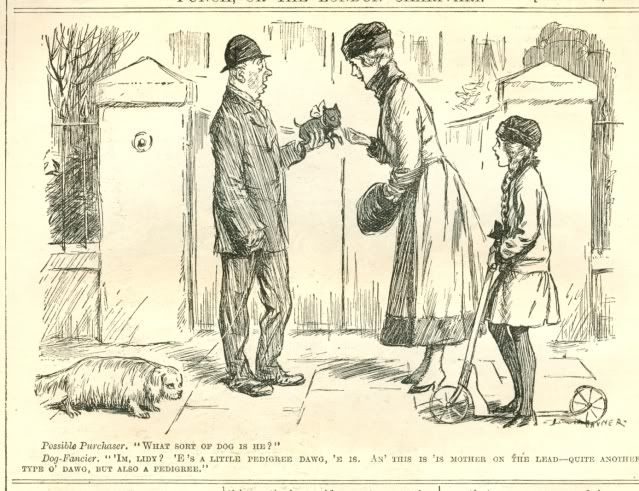

1917: Trying Too Hard

This cartoon is a rare instance where the war plays no part in the story, not even a minor part. The body language of both mother and daughter suggests that the sale is already in the bag. The dog fancier is over doing the sales patter thereby revealing that he doesn’t really understand the concept of ‘pedigree’.

The girl’s scooter looks rather like what has been popular among youngsters not that long ago.

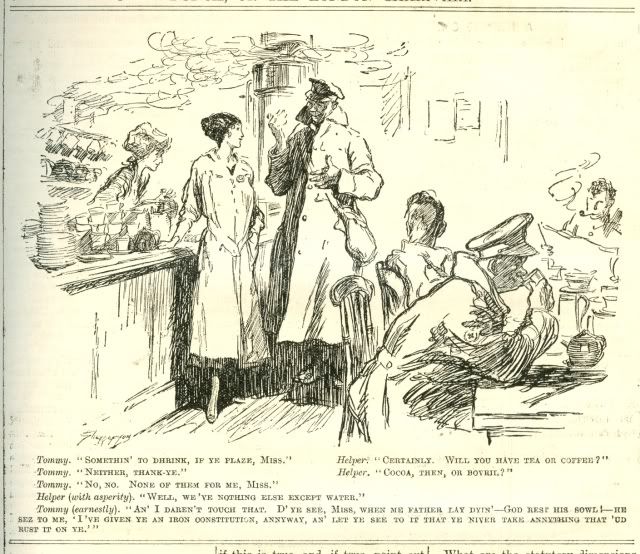

1917: What He Really, Really Wants

The helpers are comfortably off women running a canteen for ‘our brave soldiers.’ He wants booze. They are missing the point and he seems unwilling to point it out directly to them.

The cartoon is of course only a joke but one wonders whether they could really have been so naive.

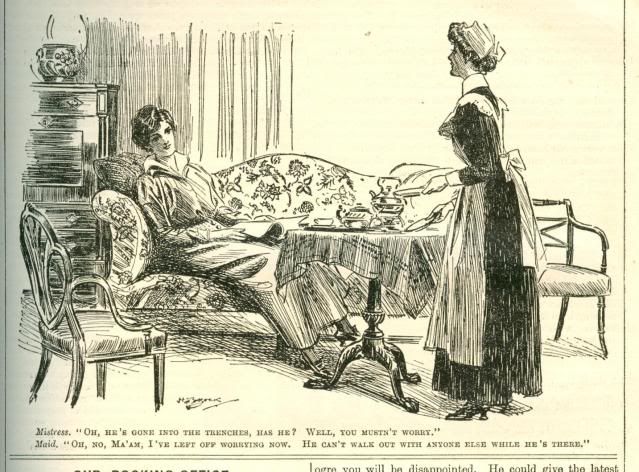

1917: She Has Left Off Worrying Now

The mistress is well aware of what risks the young man faces. The maid seems unwilling to think about them. She doesn’t even seem to have heard about Mademoiselle from Armentieres.

The expression ‘walking out’ had by then replaced the older term: courting. I imagine that there is a slight change of emphasis here. ‘Walking out’ was simply an accurate statement of what was happening. By regularly walking in each other’s company they were openly signalling the existence of a relationship which would not necessarily lead to anything permanent.

By the late 1950s when I was involved in such activities myself it was called ‘going out with’ presumably because walking was no longer a necessary part of what was going on. I recall reading in Zadie Smith’s White Teeth that in Willesden in the 1980s it was called ‘dealing with’.

What is the term used today? I rather think it is ‘is she seeing someone now?’

It seems odd that there needs to be a frequent change in the expression used.

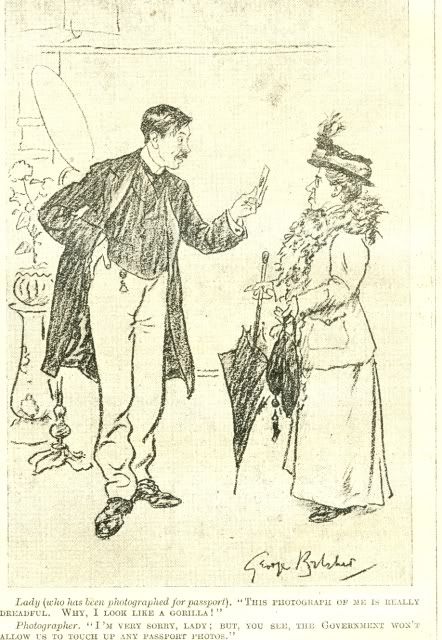

1917: Don’t You Know There’s a War On?

I am old enough to remember this refrain during World War Two whenever anyone complained. The photographer is using the war to deflect the customer’s criticism.

I am wondering why she wanted a passport. Where was she going in 1917? Sea travel would be seriously at risk from U-boat attack.

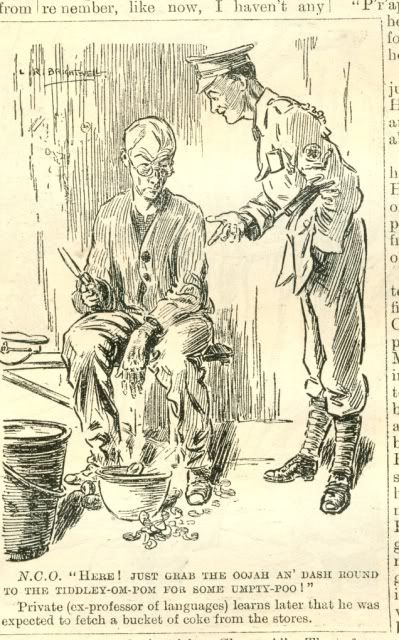

1917: A New Language to Learn

All institutions tend to develop their own terminology. The army was probably more prone to do this than others. I wonder whether the example here is an exaggeration or perhaps the artist is here correctly recording some actual slang. I have looked up some websites that list World War One army slang but have drawn a blank on the examples listed here though that doesn’t necessarily mean that they are not genuine.

During my National Service I must have encountered plenty of slang. Having now been a civilian for sixty years I can’t recall much of it. Some examples have passed into common usage. For instance, AWOL standing for Absent Without Leave is now generally understood.

I do remember one instance of army language which is not used elsewhere today. I refer to the word ‘gash’. I can best explain it by giving an example of its use. From time to time an army unit is ordered to detach one of its soldiers to some other military formation. Do they send their most exemplary person? No, of course not, they tend to send the one that they can most easily do without. That one is gash.

I sometimes suspect that some United Nations Peacekeeping soldiers are selected on a similar basis.

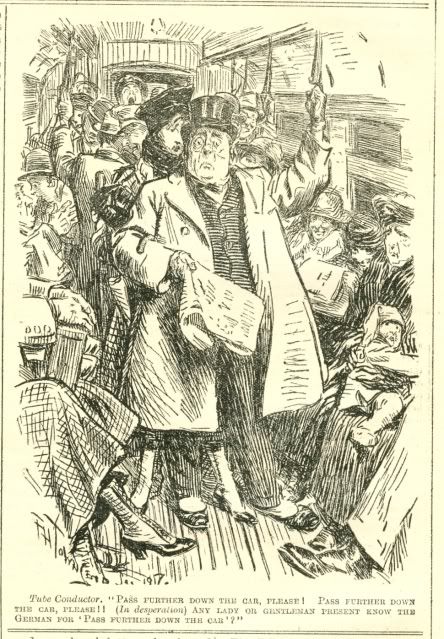

1917: The Ultimate Insult

The city gent is in a world of his own. He is probably digesting what he just read in his newspaper – most likely The Times. He doesn’t seem to like what he just read. It might be state of the war but might just as easily have been some adverse news relating to his business or his investments. If he has heard the conductor at all he doesn’t imagine that the message being uttered could possibly have anything to do with him.

The conductor is exasperated at the refusal of the man in the top hat to do what he has been told to do. In jest he suggests that if he won’t do it he must surely be a German - the object of everyone’s hate.

This cartoon suggests that every carriage on the Underground then had its own conductor. My own memory goes back to the early 1940s and there were no conductors then. On the other hand people frequently used the doors between the carriages while the train was moving in order to change carriages. This is now very much not allowed.